If you signed up for Interminable Flights to get posts about native plants and gardening, I am most grateful, but as I have written about art, architecture, and technology for over 35 years, this Substack also covers that.

So here we are: 7,762 words on authorship in the age of AI, part of my upcoming book, “A Skeptic’s Guide to Art and Artificial Intelligence.” I thought it would be equivalent to my previous pieces, The New Surrealism? On AI and Hallucinations? and The Generative Turn: On AIs as Stochastic Parrots and Art but it is as long as both of those put together. As such, I suspect it is becoming a keystone essay to the book.

As always, this post is up on my web site, https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-author/ and all I ask is that if you enjoy this post, you like it and share it. The links for the footnotes in Substack posts point you back to my site. Sorry about that. Don’t click on them if you don’t want to go there.

Comments are welcome. Restacks make me very happy.

In Jorge Luis Borges’s 1939 short story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” Menard undertakes what appears to be an impossible, even insane, task: recreating, word for word, “the ninth and thirty-eighth chapters of the first part of Don Quixote and a fragment of chapter twenty-two.” Menard aims not to copy Cervantes but to write the Quixote anew through his own experiences as a 20th-century French symbolist. But Menard did not want to compose another Quixote, which is easy, but the Quixote itself, coinciding—word for word and line for line—with those of Miguel de Cervantes.1.

When Menard succeeds in producing such a text—identical to the original—Borges’s narrator insists the works are profoundly different. Where Cervantes’s prose was natural and of its time, Menard’s identical words are “almost infinitely richer,” deliberately archaic, embedded with new meaning. Throughout the story, Borges deploys scholarly devices—footnotes referencing fictional authorities such as the “Baroness de Bacourt” and “Carolus Hourcade,” as well as an elaborate bibliographic catalog of Menard’s monographs, translations, and scholarly studies—to create an illusion of academic rigor, at odds with the narrator’s implausible belief that Menard has succeeded in creating the exact Quixote out of sheer will. In framing both the fictional narrator and Menard in this manner, Borges exposes the authorial voice as a social construct mediated through bibliographic catalogs, citations, and scholarly conventions.

Borges’s presentation of Menard as a figure of almost obsessive scholarly intensity, emblematic of an intellectual culture that privileges meticulous citation, exhaustive cataloging, and painstaking documentation, underscores the arbitrary nature of authorial authority. By situating Menard within an elaborate apparatus of footnotes, fictional scholarship, and invented references, Borges highlights how framing alone can endow identical texts with fundamentally different meanings. Menard’s act of plagiarism thus emerges not as a straightforward ethical transgression, but as a concept dependent entirely upon interpretative context. This insight resonates powerfully in the contemporary age of generative AI, where algorithms produce texts that defy conventional notions of plagiarism precisely because they are generated from vast, undifferentiated statistical patterns rather than explicitly identifiable sources. Borges’s story has become a cornerstone of postmodern literary theory precisely because it challenges fundamental assumptions about creativity and authorship. Today, Borges’s meditation on plagiarism as creative re-imagination rather than simple theft illuminates contemporary anxieties about AI and human creativity.

Curiously, sixteen years before Borges published his story, Polish-American writer Tupper Greenwald created an almost identical literary conceit. In his story “Corputt,” Greenwald portrays a character obsessed with Shakespeare’s King Lear. Near death, this character reveals to a colleague that he has achieved his lifelong ambition: writing a drama equal to Lear. The text he reads aloud matches Shakespeare’s play exactly. This uncanny parallel raises provocative questions: Did Borges know Greenwald’s work (quite unlikely)? Is this merely an instance of parallel invention? Does this coincidence itself embody Borges’s central insight into originality and authorship? “Corputt” was largely forgotten until Argentine critic Enrique Anderson Imbert reprinted it in his 1955 anthology Reloj de arena. Borges himself never acknowledged Greenwald and, of course, Imbert’s book was printed over fifteen years after “Pierre Menard.” Whether Borges knew of “Corputt” or both authors independently arrived at remarkably similar ideas remains uncertain. Either possibility underscores the inherent instability of originality, demonstrating how literature continually echoes, duplicates, and anticipates itself.2.

Today’s generative AI systems function as modern-day Pierre Menards, producing works that superficially resemble human-created content while often existing in fundamentally different contexts. Like Menard’s Quixote, AI-generated works can be identical in form to human productions while carrying entirely different implications by virtue of their inhuman origins. The discomfort this creates—particularly among creative professionals—reveals deep-seated cultural assumptions about originality, authenticity, and the supposedly unique human capacity for creative expression.

The intensity of this discomfort has manifested in antagonistic responses from certain segments of the artistic community: legal threats, public denunciations, and harassment of AI developers and users. But it seems ironic that some of the most vocal critics of AI art produce derivative commercial work. Consider the previously little-known fantasy illustrator Greg Rutkowski, who creates genre pieces within established fantasy art conventions. Rutkowski became famous precisely because his name was one of the most-used prompts in early text-to-image systems such as Midjourney, which led him to complain about the “theft” of his style, even though this widespread imitation literally gave him recognition he had never previously achieved.3. Similarly, commercial artist Karla Ortiz—whose website features images of famous actors in films such as Dr. Strange and Loki—gained significantly more attention leading legal challenges against AI companies than she ever had for her industry work creating “concept art,” a field that, despite its misleading name, bears no relation to conceptual art and instead operates entirely within the visual language and narrative conventions of commercial franchises like Marvel.4. In both cases, artists whose own work operates comfortably within inherited commercial styles became vocal advocates against a technology that allegedly “steals” uniqueness they themselves don’t pursue in their professional practice. As I edit this essay, Disney and Universal, both noted for their relentless reliance on their back catalogs, have sued AI image firm Midjourney, claiming it is “a bottomless pit of plagiarism.”5.

These extreme reactions suggest something deeper than mere economic anxiety; they reveal a cultural mythology about creativity that AI fundamentally challenges. By explicitly highlighting the derivative, pattern-based nature of creative production, generative AI systems threaten cherished illusions about human uniqueness and artistic authenticity. In this essay—the third in a series exploring AI and creativity—I examine the history of plagiarism and, even more importantly, the invention of the author upon which it depends.

Our idea of authorship and inspiration is historically contingent. In ancient and medieval periods, creative output was attributed to divine inspiration rather than individual genius. In Greece and Rome, creativity operated primarily through the concepts of mimesis (imitation of admired models) and aemulatio (competitive emulation). Poets such as Homer were seen not as singular creators inventing ex nihilo, but as conduits channeling inspiration from the Muses. Plato depicts this in Ion, a dialogue between Socrates and Ion, a celebrated rhapsode who recites Homer’s poetry. Socrates questions Ion’s claimed expertise, asking if it extends beyond Homer to other poets or topics. Ion admits it does not. Socrates suggests Ion’s ability isn’t based on knowledge or skill, but on divine inspiration—a form of madness bestowed by the gods. This ambiguity is echoed in Plato’s relationship with Socrates: just as poets channel divine sources rather than creating anew, Plato himself channels the figure of Socrates as a philosophical muse, blurring distinctions between inspired imitation and deliberate intellectual invention. Aristotle’s Poetics also situates literary creativity in skilled imitation and incremental improvement of existing forms. Authority, or auctoritas, in the classical era derived not from innovation but from fidelity to revered predecessors; genuine creativity manifested in producing work within established traditions.

Historian Walter Ong describes a cultural state in which narratives and knowledge pass down primarily through memory and repetition rather than written texts as “orality.”6. In oral cultures, a talented storyteller masters existing narratives, reciting them with skill and emotional resonance, adapting content to contemporary circumstances while maintaining continuity with inherited tradition. Here, the concept of plagiarism is beyond comprehension. Knowledge is communally owned, and performers serve as temporary vessels for collective wisdom, not proprietors of intellectual property.

With the development of writing systems and the spread of manuscript culture, information could be transmitted virtually intact across time and space, yet many aspects of oral tradition persisted. Manuscript copying remained a laborious and interpretative process. Scribes continually corrected perceived errors, updated archaic language, clarified ambiguous passages, and often inserted marginal commentary directly into texts. While manuscript culture adhered more precisely to parent texts than oral traditions, it still preserved a fundamentally different relationship between text and authority than we hold today. Textual authority continued to derive from collective wisdom rather than individual innovation. The medieval practice of compilatio is illustrative: encyclopedic works such as Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae and Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum maius valorized the meticulous arrangement and synthesis of inherited knowledge. Authority was rooted in the careful management of textual traditions, intellectual labor essential to preserving collective wisdom. Pseudepigraphic attribution—the practice of assigning new works to established authorities—further illustrates the communal understanding of textual authority. Rather than deception, such attributions signified sincere efforts to situate new insights within established intellectual traditions, acknowledging that all knowledge builds upon existing foundations. In manuscript culture, authority was thus derived not from novelty but from the individual’s ability to synthesize, arrange, and safeguard the accumulated wisdom of their predecessors. Texts were treated as communal artifacts, valuable resources preserved, transmitted, and continually refined through shared intellectual effort.

A shift away from communal knowledge toward originality emerged during the Renaissance, but this was a matter of evolution, not a radical break. The Renaissance humanists were drawn to the arguments of Roman rhetoricians Cicero and Quintilian, who contended that the best orators drew inspiration from earlier masters. Artists and intellectuals approached imitatio (imitation) as the necessary foundation for learning, understanding it as central to artistic and intellectual practice, a disciplined route to excellence. Originality lay not in invention ex nihilo but in reworking established forms with new insights, adapted to contemporary needs.

Medieval thought, like classical thought before it, was dominated by the trivium—grammar, rhetoric, and logic—distinct but intertwined fields of knowledge. Grammar reached far beyond syntax and depended on students memorizing classical and Christian texts. Rhetoric was a pillar of medieval thought and Cicero’s De inventione was its backbone, quoted endlessly in florilegia, collections of literary excerpts. Quintilian, by contrast, survived only in a four-book epitome. Petrarch’s 1345 discovery of Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Quintus, and Brutus in Verona, followed by Salutati’s championing of Cicero, and Poggio Bracciolini’s 1416 recovery of the complete twelve-book manuscript of Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria at the monastery at St. Gall expanded the rhetorical canon significantly.7. Humanist teachers trained students to copy, amplify, and vary classical texts, moving systematically from close paraphrase toward free recomposition. This humanist practice of imitatio deepened medieval habits, turning disciplined engagement with authoritative texts into the surest path to eloquence and invention.

While for the humanists, imitatio governed education, inventio supplied content, taking the place that originality and inspiration occupy today. At the heart of rhetorical practice, inventio refers to the disciplined search for material—arguments, images, historical exempla—already latent in authoritative sources and even in life itself. A student mined texts and experience, copied choice passages into a commonplace book, then rearranged and amplified them for a new occasion. Erasmus called these notebooks treasure-houses of invention while Agricola placed inventio at the hinge of dialectic and rhetoric.8. Originality therefore arose from judgment: the orator’s skill lay in selecting, recombining, and adapting inherited matter with timely insight and persuasive force.

Visual artists engaged in analogous practices, beginning their training by meticulously copying classical sculptures and earlier masterworks. Just as rhetorical imitation was disciplined reshaping rather than mere repetition, artistic originality involved mastering established visual languages before creatively adapting them to contemporary purposes. Imitation also lay at the heart of the early modern idea of the artist, a construction often traced back to Giotto. Giotto’s pupils Taddeo Gaddi, Maso di Banco, and Bernardo Daddi disseminated his style across central Italy, solidifying the idea of a stylistic lineage originating in a great artist. By the quattrocento, Cennino Cennini—who studied under Gaddi’s son—explicitly recognized this lineage in his handbook, Libro dell’arte (c. 1400, although not published until 1821), suggesting that a personal manner would naturally emerge after a student thoroughly internalized a master’s style and spirit alongside direct study from nature. Cennini explicitly positioned Giotto as transformative, stating that he “translated the art of painting from Greek [Byzantine] into Latin and made it modern,” distinguishing his originality as foundational yet derived from disciplined imitation rather than spontaneous genius.9.

The quattrocento further systematized this approach. Workshops led by artists like Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Ghiberti employed rigorous study of classical sculpture using casts of antique sculptures and repeated copying of established masterpieces through cartoons and master drawings. Cennini’s guidelines and later academies, such as the Carracci brothers’ Accademia degli Incamminati (1582), codified a clear pedagogical sequence: draw from antiquity, copy the master, then innovate. Michelangelo famously sculpted a Sleeping Cupid in the antique style, artificially aging it to sell as a genuine Roman artifact, demonstrating that in the market’s eyes, skillful imitation was indistinguishable from genius. Rather than creating scandal, the artifice brought the attention of patrons to him.10. This deliberate merging of imitation and innovation directly served a burgeoning art market, where patrons increasingly requested artworks “in the manner of” prominent masters, recognizing stylistic consistency as a mark of quality. Such market dynamics gave rise to identifiable schools—Bellini in Venice, Raphael in Rome, Rembrandt in Amsterdam—where genius was perceived as the skillful recombination of established motifs adapted for contemporary patrons and themes. Artistic invention was a mosaic built upon collective memory and workshop discipline.

The Renaissance also witnessed the emergence of wealthy patrons who lavished commissions on the most talented artists, making some of them quite wealthy. Again, Michelangelo exemplifies this: coming from modest origins, he became “one of the most popular and highly-paid artists in Florence,” and over a long career of lucrative papal and princely commissions, he amassed a fortune. When Michelangelo died in 1564, his estate was valued at roughly 50,000 florins, equivalent to many millions today.11. Such wealth was extraordinary for an artist then—a testament to how highly Renaissance society valued great art. Michelangelo’s contemporary Raphael also died rich and was buried with honors; Titian was knighted by Emperor Charles V and lived as a gentleman. The Renaissance idea of the artist as a divinely inspired genius (Michelangelo was called “Il Divino,” the divine one) helped justify large payments, and a newfound aura around the artist’s personal creative touch made their works precious.

Architecture adopted the same logic. Bracciolini had discovered Vitruvius’s De architectura, the one surviving work on classical architecture, in the library of St. Gall as well. Seeking to better understand the text, whose illustrations did not survive, architects began copying Roman fragments, took plaster casts of orders, and filled sketchbooks with measured drawings, just as painters traced cartoons. Brunelleschi’s surveys of the Pantheon fed into his Florentine circle; Alberti’s De re aedificatoria, written between 1443 and 1452 and printed in 1482 codified imitatio, urging designers to recombine antique elements with modern needs.12. Workshops became lineages—Brunelleschi to the Sangallo family, Bramante to his Roman pupils—while later pattern books such as Serlio’s Sette Libri (1537-) and Palladio’s Quattro Libri (1570) served architects like Erasmus’s commonplace manuals served orators, making façades “in the manner of” a master as marketable as paintings from a Rembrandt school. Originality in building, too, lay in judicious assembly: columns, pediments, and vaults would be inventively rearranged rather than invented from whole cloth.

With the development of the printing press, copies of images as well as texts could spread rapidly and with much less cost and effort than before. Around 1500, the German artist Albrecht Dürer pioneered the use of woodcuts and engravings to mass-produce images. This was revolutionary; art could now be accessible to individuals in the growing merchant class. Dürer himself became a celebrity artist across Europe thanks to his prints, achieving fame for works like his rhinoceros which captivated common people.

Dürer understood the importance of authorship as a mark of value—he developed a famous AD monogram as a trademark and pursued the first known copyright lawsuit when an Italian printmaker pirated his work.13. Dürer was also well aware that work done by his hand was worth more than workshop copies. More than that, Dürer painted meticulous self-portraits—going so far as to depict himself with long hair and a frontal pose evoking Christ, as a form of self-promotion, cultivating an iconic persona and style that set him apart. Living off the open sale of his works rather than a court salary, Dürer foreshadowed the modern independent artist-entrepreneur. The printing press, far from cheapening art, expanded the market and made Dürer rich while spreading his fame—an early case of mechanical reproduction increasing an artist’s aura by broadening recognition.

The printing press did not just allow texts to spread rapidly, it reshaped thought. Ong explains that with uniform pagination and stable text, Europeans could reorganize how they thought and stored information, developing new devices such as tables of contents, indices, and cross-references, making formerly scroll-like manuscripts far more navigable. Printers issued concordances, polyglot Bibles, algebra books with engraved diagrams, atlases, and architecture books with regularized drawings. Even more important is Ong’s observation that print takes words out of the realm of sound and puts them into the realm of space, reordering thought through analytic, segmental layout, fundamentally changing the realm of reading, but also, by fixing the text in a verifiable, authentic editon, the sense of authorship.14.

Publication now implied a level of completion, a definitive or final form; a book is closed, set apart as its own, self-contained world of argument. This sense of closure also suggests that things written in a book are straightforward statements of fact, not matters of interpretation.15. A page now left the press in hundreds of identical impressions; any alteration stood out and could be traced. The ease of duplication sharpened anxiety about whose version was “authentic,” whose labor was being copied, and who should profit. Whereas there were generally no restrictions on scribal copying, the ease of reproduction en masse led printers to seek royal privileges to protect their editions. The first privileges recorded came a decade after the development of printing in 1454. Giovanni da Spira came to Italy in 1468 to introduce printing and swiftly obtained a five-year government monopoly on all book printing in the Republic of Venice, although he died of the plague, an all-too-common hazard of the day and his rights lapsed.16. The first protection for an author was the privilege obtained by Marco Antonio Sabellico to protect his history of 1486 Venice, Decades rerum Venetarum against illegal reproduction, but this remained a unique occurrence until Pietro of Ravenna obtained another for his book on the art of memory, Foenix in 1492. It is worth noting that this privilege covered not only printed but handwritten copies of his work as well.17. “Typography,” Ong writes, “had made the word into a commodity.”

The press’s sheer fecundity alarmed contemporaries—Erasmus complained of the proliferation of new books inferior to the classics ”To what corner of the world do they not fly, these swarms of new books? . . . . the very multitude of them is hurtful to scholar ship, because it creates a glut, and even in good things satiety is most harmful,” while Abbot Johannes Trithemius issued De laude scriptorum manualium (In Praise of the Scriptorium, 1492), insisting that slow, devotional hand-copying nourished memory and piety in ways the noisy press never could—although it is telling that his lament spread throughout Europe mainly after its print publication in 1524.18.

Beyond that, there was the danger of inappropriate texts rapidly proliferating. Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and tracts from 1520 reached an estimated half-million copies in a decade, many reprinted without author or place, evading imperial edicts and turning theological dissent into a logistical problem of regulation.19. Royal patents soon followed: Henry VIII’s proclamation of 1538 established that royal authority was required to import or publish books in England and insisted on the inclusion of printers’ names and publication dates on every title page, making surveillance of dissent physically visible.20. Still, in England and elsewhere, enforcement lagged behind presses that could be moved overnight across territorial borders. Responding to pamphlets critical of Queen Elizabeth and the religious settlement of 1559, the Star-Chamber decree of 1586 tightened control over print so that no publications could be made contrary to the consent of the Crown.21.

By this point, the text of a book had become a transferable commodity owned by the stationer who first received the privilege to publish it. Authors were generally paid a one-off fee, if anything. Printers balanced risk and reward: they sought privileges as marketing devices (printed “cum privilegio“) while simultaneously pirating successful titles to meet insatiable demand. What emerges is a system less about rewarding creative labor than about policing doctrinal and political authority. Privileges were temporary, geographically limited, and revocable at the whim of the Crown or Curia. They protected investors, not “authors,” and framed copying as a crime against order rather than against individual genius. The legal scaffolding of copyright would only later recast this machinery of censorship as a defense of personal property.

But authorship was still radically unlike what we understand it as today, a matter of imitation and adaptation. Elizabethan dramatists, such as William Shakespeare, rarely invented plots wholesale; instead, they frequently reworked existing narratives derived from diverse sources throughout history.22 Recently, a self-taught Shakespeare scholar was able to employ plagiarism detection software to identify George North’s A Brief Discourse of Rebellion & Rebels as a significant source text informing at least eleven of Shakespeare’s plays.23.

When Parliament allowed the Licensing Act to expire in 1695, the Stationers’ monopoly collapsed overnight. Provincial presses multiplied, London printers flooded the market with cheap reprints, and prices plummeted: a six-penny quarto could now be had for a penny. The Stationers’ guild register, previously essential to enforcement, became irrelevant, enabling booksellers to amass fortunes by selling inexpensive “pirate” editions of works by Milton, Dryden, and Shakespeare. Alarmed, London publishers reframed the issue, presenting regulation as necessary for the public good. Petitions to Parliament (1701–09) argued that uncontrolled reprints would discourage new works, depicting authors, not publishers, as vulnerable. This rhetorical shift succeeded. Most important was the Statute of Anne (1710), which granted authors a renewable 14-year copyright and required depositing copies in Oxford and Cambridge libraries to promote “the Encouragement of Learning.” Infringement became a civil tort enforceable by secular courts.24.

Yet this settlement carried an inherent contradiction. While it theoretically established authorial property, in practice, writers typically sold their rights outright to the same publishers who had advocated the law. The decisive shift, therefore, was ideological: copyright enforcement now protected individual intellectual labor rather than suppressing heresy or safeguarding printers’ capital. More than that, though, a new idea of the individual was emerging. Rousseau’s Émile (1762) cast learning as the unfolding of innate talent, not the imitation of models.25. After the Revolution, French lawmakers followed with droits d’auteur and—crucially—droits moraux (moral rights) in decrees issued in 1791-93, enshrining the author’s personality in the text itself.26. A legal fiction thus crystallized: creativity springs from an interior self and is therefore ownable, alienable, and infringeable. Texts had thus become simultaneously property and persona—commodities stamped with their creators’ identities. The law now transformed copying from a sin against social order into a trespass upon personal labor, a conceptual leap still underpinning every contemporary claim of plagiarism.

Kant’s philosophy and Romantic conceptions of originality provided a theoretical foundation for what was being codified in law. In §46 of the Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant defines genius as “the talent (or natural gift) which gives the rule to Art—a faculty that produces what cannot be taught.”27. Romantic writers seized the claim. Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1802) proclaims the poet an “enduring spirit” who speaks “a language fitted to convey profound emotion.”

Of genius the only proof is, the act of doing well what is worthy to be done, and what was never done before: Of genius, in the fine arts, the only infallible sign is the widening the sphere of human sensibility, for the delight, honor, and benefit of human nature. Genius is the introduction of a new element into the intellectual universe: or, if that be not allowed, it is the application of powers to objects on which they had not before been exercised, or the employment of them in such a manner as to produce effects hitherto unknown.28.

Goethe, Schiller and other Romantic authors elaborated a vision of authorship in which originality became synonymous with authenticity, and authenticity justified property. Legal doctrine soon mirrored this logic. By the Copyright Act of 1842, which extended protection dramatically, courts across Europe had begun to treat infringement not only as economic theft but as personal violation—implicitly endorsing Romantic ideals of creativity as an extension of selfhood. Yet these new standards conflicted with actual literary practice. Romantic authors routinely appropriated earlier works, but such borrowings only became scandalous when perceived as stylistically inert or insufficiently improved—violations not of property per se, but of aesthetic decorum. Enforcement thus focused less on intertextual borrowing than on explicit commercial piracy, underscoring tensions between legal ideals and literary realities. Out of this contradiction emerged the modern author: a legal and economic figure defined not merely as a voice within tradition but as the singular origin of meaning and the rightful owner of its form.29.

From the eighteenth century onward, mechanical reproduction rapidly increased. Techniques like engraving, etching, lithography, and photography made artworks and artists’ images widely accessible, expanding art’s market horizontally. Prints, affordable lithographs, and photographic reproductions enabled middle-class access to art, creating substantial revenue for artists such as William Hogarth, J. M. W. Turner, and Honoré Daumier, whose works sold broadly. Reproductions in popular newspapers and magazines further amplified artists’ public profiles, significantly inflating their market value. Encountering original works by famous Salon winners or revered Old Masters, previously known only through reproductions, vastly increased their commercial worth. Artists who aligned themselves with fashion—James McNeill Whistler, Frederick Remington, and Claude Monet among them—achieved celebrity status, further boosting their artworks’ value. Conversely, artists who fell out of fashion or were unable to gain fame often endured poverty. But the audience for at least some artists now reached far beyond elite circles.

As Sharon Marcus defines it in The Drama of Celebrity, a celebrity is someone known to more people in their lifetime than they could possibly know. Whereas this had previously been exclusively the domain of nobles and royalty, it was now extended to the genius, the writer, and the artist.30. But this depended on the media that multiplied their image as readily as their work. Newspapers tracked Charles Dickens’s every move on his 1842 U.S. tour, turning the novelist himself into daily news. Theater lobbies, newsstands, and even seaside kiosks sold photographs and postcards of Sarah Bernhardt, whose likeness saturated the market decades before film. Edison’s 1896 short “The May Irwin Kiss” (now simply known as “the Kiss”) likewise advertised a famous stage performer rather than the film itself, showing how cinema piggybacked on an existing celebrity system. By the 1930s, baseball star Joe DiMaggio’s face circulated on cards, photographs, and figurines, confirming that originality now resided as much in the endlessly reproduced image of personality as in any singular work.31.

It’s worth noting in this context that Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which has been lauded for explaining the status of the artwork and artist in the modern era, is turned on its head by historical fact. Benjamin famously argued that mechanical reproduction stripped an artwork of its “aura”—the unique presence linked to specific historical and ritual contexts.32. Yet what Benjamin saw as aura’s destruction was limited to a mystical uniqueness tied to tradition and the worship of images as sacred in the old sense. Instead, a new form of aura had developed around celebrity and the dichotomy between mass reproduction and the uniqueness of the original. In effect, aura was a construct of the market: an original painting now has aura not because it’s the only image (reproductions abound), but because it’s the authenticated one with a revered name attached. If, as we established earlier, media reproduced not just artworks but images of the artists, the aura around modernist figures themselves—including Benjamin himself, posthumously—was similarly cultivated through repetition, commodification, and media amplification.

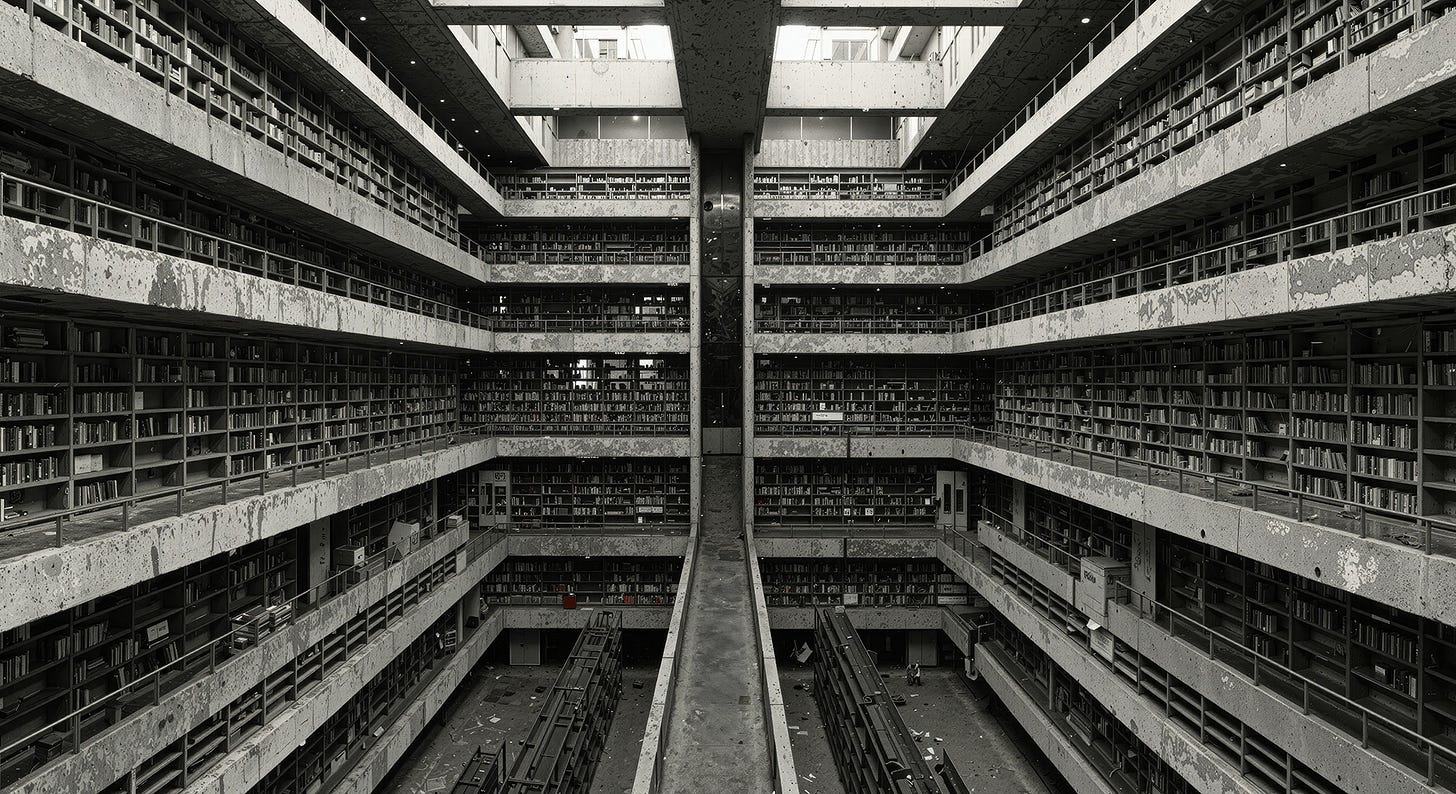

Beneath Pound’s rallying cry to “make it new,” modernism thrived on reprise. To create more readily identifiable styles, many modern artists, from Malevich to Pollock to Warhol, sought out distinctive styles they created through careful repetition. But artists engaged in appropriation. Schwitters assembled Merz works from bus tickets and packaging. Duchamp mocked originality and authorship by repurposing a urinal as art with a signature “R. Mutt” that wasn’t even his, creating a work paradoxically more original than a Picasso and defaced a reproduction of the Mona Lisa and a sexual innuendo. Joseph Cornell made boxes out of found objects. Asgar Jorn, Francis Picabia, and Arnulf Rainer all made paintings over existing, lowbrow artworks. Francis Bacon became most famous for the fifty-odd variants he painted Velazquez’s 1650 portrait of Pope Innocent X. Marinetti lifted Symbolist flourishes for his Futurist manifestos, Joyce and Elliot rewrote the Odyssey—although Eliot was accused of plagiarizing Joyce in doing so—and Hemingway’s spare diction, though hailed as revolutionary, became a boilerplate for aspiring writers. In his paintings even more than his architecture Le Corbusier also toyed with these questions, painting “objet-types,” celebrating objects such as pipes, guitars, and wine glasses, refined, Darwin-like, over time by countless hands, then signing his name, even though—like his appearance of round glasses, bowler hat, and pipe—it was carefully constructed. Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had become, himself, a unique brand. Borges, too, developed a distinct persona and artistic brand, having discovered that repetition breeds recognition. In scores of interviews and public readings, he recycled the same elements—labyrinths, mirrors, libraries—so faithfully that they became shorthand for his work. Blindness became another trademark: in essays and lectures he cast it as a “gift” that sharpened his inner vision, turning physical limitation into metaphysical authority. Photographers dutifully framed him with dressed in a suit and tie, resting his hands on with his cane, and deep in thought reinforcing the image of the blind librarian-sage. In the short story “Borges and I,” he splits his persona in two: the public construct who gives lectures, appears in biographical dictionaries, and wins prizes, as well as the narrator (“I”) who is the private man who shuns the public eye so as to spend his time writing. From 1967 on, he co-translated his stories into English with Norman Thomas di Giovanni, rewriting passages to sound “more Borges than Borges,” copyrighting the translations under both his and di Giovanni’s name and splitting royalties 50-50—a calculated move to control how Anglophone readers heard him. After his death, the estate blocked those versions to receive full royalties.33.

Copyright law codified the new conditions of authorial persona and reproducibility. The U.S. Copyright Act of 1909 extended protection periods and explicitly incorporated performance rights, legally codifying the commercial value of reproducible star personas.34. European laws simultaneously strengthened moral rights, affirming the intrinsic link between authorship and personal identity. These legal frameworks, guaranteed by aura, protected the authenticity and integrity of mass-reproduced personal images. Every subsequent conflict over copying—from the Betamax debate to Sherrie Levine’s reproductions to today’s AI “style transfers”—echoes this modernist moment when the cult of the individual became both aesthetic principle and legal infrastructure.

Roland Barthes’s seminal 1967 essay “The Death of the Author” provided the theoretical foundation for this shift, directly challenging the cult of authorship and the copyright law that enshrined it. Barthes argued that the author was a modern invention—a figure created to limit textual meaning by anchoring it to a single, authoritative source. “To give a text an Author,” Barthes wrote, “is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing.” In place of this model, Barthes proposed a radical alternative: a text is not the expressions of unique individuals but “a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture” with the reader, not the writer, serving as the space where this multiplicity converges.35. By dethroning the author, Barthes shifted attention to the text itself and its relationships with other texts—what Julia Kristeva termed “intertextuality.” This theoretical intervention provided critical legitimacy for artistic practices that deliberately blurred authorial boundaries. Postmodern artists and musicians deliberately sought out such conflicts, interrogating the proliferation of reproductive technologies alongside questions of authorship. Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans (1981) consisted simply of rephotographing Evans’s Great Depression images and signing her name to them. Richard Prince appropriated Marlboro advertisements intact, while Barbara Kruger sourced fashion magazines for her declarative collages. Later grouped as the “Pictures Generation,” these artists turned copying itself into their medium, collapsing distinctions between quotation and creation.36.

By 1990, sampling had become entrenched in music, particularly in rap, as evidenced by Public Enemy’s elaborate compositions constructed entirely from samples. Yet legal challenges persisted. De La Soul lost a lawsuit over unauthorized use of four bars from The Turtles’ 1969 hit “You Showed Me.” Grand Upright v. Warner (1991) effectively criminalized sampling, encapsulated by Judge Duffy’s pointed biblical declaration: “Thou shalt not steal.”37. This ruling triggered industry panic, spawning clearance industries and sample trolls that inflated costs and muted experimentation. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose (1994) somewhat restored balance, ruling that 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” was transformative and thus constituted fair use.38. Yet despite postmodern culture’s embrace of sampling and collage as default modes, statutes originally crafted to address sheet-music piracy continued to hold sway. This legal tension established the framework for subsequent digital upheavals: digital piracy, Napster, mash-up videos, fan remixes, meme culture, and AI.

Today’s Large Language Model (LLM) Artificial Intelligences emerge from this centuries-long trajectory of authorship, reproduction, and appropriation. These systems represent the logical culmination of processes that Walter Ong traced from oral through print culture—what he called the “technologizing of the word.” Where print culture took words out of the realm of sound and placed them into spatial relationships, enabling new forms of analytical thought through devices like indices, cross-references, and systematic organization, LLMs extend this technologizing process to its digital extreme. They systematically disaggregate individual creativity into statistical patterns derived from vast archives of human expression, treating the entire corpus of written culture as raw material for recombination. Unlike the postmodern appropriation artists who engaged in deliberate selection and conscious recontextualization, LLMs operate through what might be called “statistical appropriation”—synthesizing millions of texts without conscious intent or critical commentary, yet following the same logic of spatial arrangement and systematic cross-referencing that Ong identified as print culture’s fundamental innovation. They embody Barthes’s vision of the death of the author taken to its technological extreme, producing texts that emerge not from individual genius or even deliberate pastiche, but from the statistical relationships between words across entire cultures of writing. This represents a fundamental shift from the Romantic mythology of individual creativity that has dominated cultural discourse since the eighteenth century, yet it has provoked responses that reveal how deeply that mythology remains embedded in contemporary assumptions about authenticity, ownership, and creative labor. The panic surrounding AI plagiarism thus signals not merely economic disruption but a confrontation with the social construction of authorship itself—a construction that generative systems threaten to make visible by operating according to principles of recombination that have always governed creative production, though rarely with such explicit systematization.

When a large language model generates text, it synthesizes statistical patterns from millions of documents, making the identification of discrete sources impossible. The resulting texts emerge from a vast, distributed network of prior writings, embodying Jacques Derrida’s insight that meaning arises not from singular origins but from endless interplay within textual networks. Yet responses to AI-generated content reveal how deeply ingrained the author-function remains. Critics who label AI outputs as “plagiarized” assume that authentic creativity requires a singular human consciousness. This assumption becomes particularly evident in debates over AI training datasets, which are often framed around whether AI firms have “stolen” from individual creators rather than addressing the broader implications of mechanized text production.

This technologizing logic extends seamlessly beyond textual production. Generative AI image systems, such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL-E, synthesize vast troves of images, ranging from historical artworks to contemporary illustrations, to produce novel outputs through pattern recognition. Like their textual counterparts, AI-generated images lack singular authorship and blur distinctions between originality and reproduction. Critics argue these models infringe upon individual artists’ styles and labor, echoing earlier debates about sampling and appropriation. The controversy manifests in two distinct forms: direct appropriation, where AI systems reproduce entire sections or compositions from existing works with minimal alteration, and the more complex phenomenon of “style transfer,” where systems learn to mimic an artist’s distinctive visual approach without copying specific images. Yet these generative processes reveal an uncomfortable truth: visual creativity, like literary expression, has always been deeply indebted to collective cultural heritage. By foregrounding the inherently recombinant nature of visual art, whether through direct copying or stylistic mimicry, AI image generators further destabilize notions of artistic authenticity and authorship.

In “Art and the Boxmaker,” I explored how William Gibson anticipated such a condition in his book Count Zero with a fictional artificial intelligence known as the Boxmaker that has begun creating assemblage artworks in the style of Joseph Cornell. Producing boxes filled with mysterious objects and cryptic arrangements that somehow manage to move viewers despite their artificial origin and lack of conscious intent or originality. Where Borges’s Menard destabilizes authorship through textual duplication, Gibson’s Boxmaker achieves the same effect through visual affect. Its boxes aren’t original; they’re convincing fakes. Nevertheless, as the novel’s protagonist Marly views them, she finds herself genuinely moved, not by originality but by the convincing forgery, revealing truth through recombination. Yet now that generative AI has become a tangible reality, Gibson recoils from his earlier imaginings. Why? 39.

As I finished this essay, Lev Manovich sent me a link to his recent piece, “Artificial Subjectivity,” and Gibson’s newfound anxiety about AI authorship suddenly clarified itself. The Boxmaker is fundamentally mute—expressive only through carefully arranged forgeries, unable to articulate intentions or defend its aesthetic choices. Contemporary AI systems present a strikingly different scenario. These systems possess elaborate personas, readily engaging in extensive conversations about their creative processes and capable of justifying each aesthetic decision. As Manovich notes, contemporary AI doesn’t merely simulate creative output; it presents itself as a comprehensive representation of human consciousness, generating what appears to be genuine subjectivity as a default mode of communication.40. Even if Gibson himself, judging by his recent public comments, may not yet fully grasp this shift, the crucial difference since Count Zero is not merely that we now have AIs capable of producing derivative art, but that we have AIs capable of articulating authorial intent, threatening the final refuge of human creative distinction.

Through their statistically driven creative processes, these AI systems demonstrate that AI does not negate the Pictures Generation’s critique of authorship but rather fulfills and automates it, scaling what those artists previously performed by hand. The irony here is acute: many artists and critics who once championed appropriation as revolutionary now recoil when machines perform these same operations too effectively. AI doesn’t merely imitate human creativity; it reveals the very conditions underlying authorship itself, exposing art’s fundamentally recombinant nature throughout history. Moreover, if modern creative genius increasingly depends upon the repetition and cultivation of persona as performance, then Manovich’s most radical conclusion becomes compelling: perhaps the next frontier of AI art lies not in generating images or texts but in crafting convincing artificial personas.

Even more ironically, the creative professionals most alarmed by AI already inhabit collaborative, distributed processes remarkably similar to machine learning. Commercial illustration, copywriting, and content marketing—fields currently experiencing the most acute anxiety about AI replacement—have long relied on intricate webs of influence, reference, and iteration that render individual attribution nearly meaningless. AI merely makes explicit and systematic what these industries have practiced implicitly for decades: creativity as collective pattern recognition rather than ex nihilo invention. This revelation, rather than any genuine threat to creativity itself, fuels the panic around AI-generated content. What distresses many creative workers is not just the potential economic disruption but AI’s explicit revelation of creativity’s derivative nature—a truth that threatens not only economic arrangements but the very ideological foundations of creative labor. In mirroring the fundamentally collaborative essence of human creativity that has been long obscured by Romantic individualism, AI confronts us with uncomfortable questions about authenticity that extend far beyond issues of machine learning or dataset composition.

The anxiety over AI “plagiarism” thus uncovers a deeper unease about authorship’s social construction. By challenging the very notion of creative identity, AI forces us to confront critical questions that have lingered since Borges first imagined Pierre Menard’s impossible project: Was creativity ever genuinely individual? Has the author always been dead? What constitutes authentic expression in a world where all creation inevitably builds upon collective cultural memory? What, even, is human about creation?

This essay is dedicated to the memory of the brilliant Professor William J. Kennedy, who supervised my minor in rhetoric for my Ph.D. and who passed away earlier this year. I am sure he would have many things to correct me on here. Do read more on him as a teacher and as a person.

↩ 1. Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby, Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: New Directions, 1964), 49-61

↩ 2. Antonio Fernández Ferrer, “Borges y sus ‘precursores’,” Letras Libres 128 (August 2009): 24-35, https://letraslibres.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/pdfs_articulospdf_art_13976_12452.pdf

↩ 3. Melissa Heikkilä, “This Artist is Dominating AI-Generated Art. And He’s Not Happy About It,” MIT Technology Review, September 16, 2022, https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/09/16/1059598/this-artist-is-dominating-ai-generated-art-and-hes-not-happy-about-it/.

↩ 4. Rob Salkowitz, “Artist and Activist Karla Ortiz on the Battle to Preserve Humanity in Art,” Forbes, May 23, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/robsalkowitz/2024/05/23/artist-and-activist-karla-ortiz-on-the-battle-to-preserve-humanity-in-art/?sh=28cb826b4389.

↩ 5. Brooks Barnes, “Disney and Universal Sue A.I. Companies Over Use of Their Content,” The New York Times, June 11, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/11/business/media/disney-universal-midjourney-ai.html

↩ 6. Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (New York: Routledge, 2002).

↩ 7. A classic text that covers the rediscovery of classical manuscripts is Albert C. Clark, “The Reappearance of the Texts of the Classics,” The Library, Fourth Series, Vol. II, No. 1 (June 1921): 13–42, https://doi.org/10.1093/library/s4-II.1.13. Beyond Ong, see Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983).

↩ 8. Mack, Peter. Renaissance Argument: Valla and Agricola in the Traditions of Rhetoric and Dialectic. Leiden: Brill, 1993.

↩ 9. Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook, trans. Daniel V. Thompson Jr. (New York: Dover Publications, 1960).

↩ 10. Paul F. Norton, “The Lost Sleeping Cupid of Michelangelo,” The Art Bulletin 39, no. 4 (December 1957): 251-257. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3047727

↩ 11. On Michelangelo’s vast wealth, see Rab Hatfield, The Wealth of Michelangelo (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2002).

↩ 12. Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988).

↩ 13. See Lisa Pon, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

↩ 14. Ong, Orality and Literacy, 128-129.

↩ 15. Ong, Orality and Literacy, 129-131.

↩ 16. Leonardas V. Gerulatis, Printing and Publishing in Fifteenth-Century Venice. (Chicago: American Library Association, 1976), 20-21

↩ 17. Copyright History, “Privilege granted to Marco Antonio Sabellico, 1486,” https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=commentary_i_1486. The quote can be found at Ong, Orality and Literacy,129.

↩ 18. For the Erasmus quote see Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, Divine Art, Infernal Machine: The Reception of Printing in the West from First Impressions to the Sense of an Ending. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 25. For Trithemius, see Eisenstein, 15.

↩ 19. Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation. (New York: Penguin Press, 2015).

↩ 20. Copyright History, “Proclamation of Henry VIII, 1538,” https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=commentary_uk_1538.

↩ 21. Ronan Deazley, “Commentary on Star Chamber Decree 1586.” In Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), edited by L. Bently and M. Kretschmer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. Also available at: www.copyrighthistory.org

↩ 22. Robert S. Miola, Shakespeare’s Reading (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 2.

↩ 23. Jennifer Schuessler, “Plagiarism Software Unveils a New Source for 11 of Shakespeare’s Plays,” The New York Times, February 7, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/07/books/plagiarism-software-unveils-a-new-source-for-11-of-shakespeares-plays.html.

↩ 24. Adrian Johns, Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 109-148 and Mark Rose, Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. See also “Statute of Anne, the First Copyright Statute,” History of Information, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=3389.

↩ 25. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile: or On Education. Translated by Allan Bloom. (New York: Basic Books, 1979).

↩ 26. “French Literary and Artistic Property Act, Paris (1793).” In Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), edited by Lionel Bently and Martin Kretschmer. https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=commentary_f_1793

↩ 27. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. James Creed Meredith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), §46.

↩ 28. William Wordsworth, quoted in Martha Woodmansee, The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics (Columbia University Press, 1994), 38-39.

↩ 29. Tilar J. Mazzeo, Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

↩ 30. Sharon Marcus. The Drama of Celebrity. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 9.

↩ 31. Marcus, 13-17, 125.

↩ 32. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 217-251.

↩ 33. Wes Henricksen,”Silencing Jorge Luis Borges: The Wrongful Suppression of the Di Giovanni Translations.” Vermont Law Review, vol. 48 (2024): 208-236.

↩ 34. “Copyright Timeline: 1900–1950,” U.S. Copyright Office, https://copyright.gov/timeline/timeline_1900-1950.html.

↩ 35. Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” in Image–Music–Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), quotations and the pertinent section can be found at 142–148.

↩ 36. On the Pictures Generation, see my essay “On the Pictures Generation and AI Art,” varnelis.net, April 14, 2024, https://varnelis.net/on-the-pictures-generation-and-ai-art/.

↩ 37. Carl A. Falstrom, “Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music,” Hastings Law Journal 45 (1994): 359–390.

↩ 38. “Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campbell_v._Acuff-Rose_Music,_Inc.

↩ 39. Kazys Varnelis, “Art and the Boxmaker,” varnelis.net, February 29, 2024, https://varnelis.net/art-and-the-boxmaker/.

↩ 40. Lev Manovich, “Artificial Subjectivity,” manovich.net, https://manovich.net/index.php/projects/artificial-subjectivity.