Two things.

First, this year I'm writing much more. It's curious—when I aimed to write just one essay per month, as I did last year, the task felt daunting. Yet now, averaging one essay a week, I have established a rhythm. The process feels easier. The more I write, the more energized I become, and new ideas emerge readily. I have at least eight essays in the works now—for the Florilegium, on AI (this is one of a series of shorter posts on the topic) and art, on the fate of network culture. The rhythm of regular practice sustains itself.

My friend Adam Greenfield recently articulated a similar sentiment on his Patreon:

Maybe it’s simply the onset of British Summer Time overnight, but I’m just bursting with energy. I know it seems incongruous with the ambient psychic weather of the moment, but then maybe that’s the point? To meet the grim farce of mainstream public affairs with an upwelling, irrepressible, literally insurgent joy? To keep at it, generating connection and possibility and the conditions of life, until the very moment the choice to continue doing so is in one way or another taken out of your hands. There are worse programs to commit oneself to, you know? (link)

Well said. My recent pace of writing starkly contrasts with my paralysis during the first Trump administration. Although I had quit full-time teaching in 2015 to focus on writing and art practice—and despite a wildly successful 2016 highlighted by the Detachment exhibit in Vilnius—after the election, I stumbled. For three years, I barely wrote, turning inward instead, absorbed by the restoration of our house. Then, just as I laid plans for a new push, COVID hit. My reserves were already empty and another year was lost. Those years betrayed the promise I had made to myself when stepping away from teaching—to finally bring forth the work I had long conceived but never had time to produce. I had all the time in the world and what came out of it? This hiatus nearly ended my career. I had surrendered to circumstance, letting external forces dictate my creative life. But in the unexpected and renewed face of a new Trump regime, I have a different response this time: “What do we say to the God of Death? Not today.” As Adam suggests there's true power in meeting grim circumstances with "insurgent joy" generating possibility, not just watching as “the darkness drops again.” And so, onwards.

You should subcribe to Adam’s Patreon. It’s good. We disagree on some things, like the state of AI today, but we agree on many others. Discourse, dialogue, and debate are what we need today, not arm-waving from censors and hard liners of all stripes. As Yeats also observed in “The Second Coming,” we cannot allow a situation where "the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity."

Second, to paraphrase Star Wars, many AIs died to bring you this message. I uploaded an earlier version to ChatGPT to get feedback and look for typos (ChatGPT and Claude make decent, albeit not perfect, copy editors). Soon after I did, my account was banned for “advocacy of sexual violence.” What? I condemn sexual violence, had my account been hacked? Then I remembered the quote from Rosalind Krauss below about the “treat of castration.” We have a long way to go before we get to real artificial intelligence, apparently.

Finally, as always, the only thing I ask of you is to pass my Substack on to other folks you think might be interested in it. Or send them to my varnelis.net. This post is at https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/the-new-surrealism-on-ai-hallucinations/

The footnote links actually work there and the images are larger, so it may prove a more rewarding reading experience.

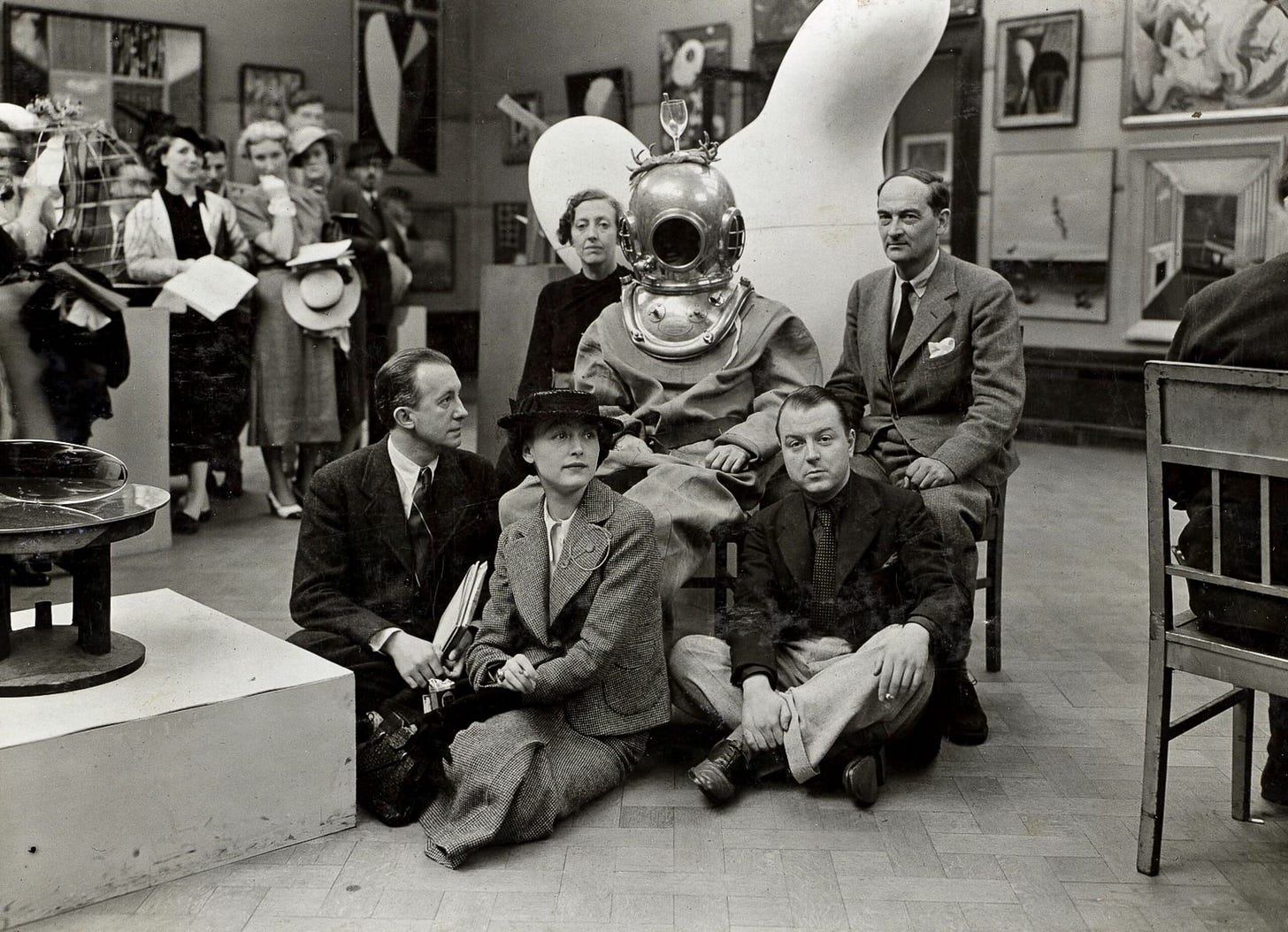

In the summer of 1936, Salvador Dalí appeared before an audience at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, clad in a diving suit, to deliver a lecture. Dalí intended, he later claimed, to illustrate his plunge into the depths of the human unconscious. He soon, however, faced a severe crisis when the suit’s air supply malfunctioned, nearly suffocating him. Assistants used a billiard cue to pry off the helmet, and Dalí proceeded to present his slide show, albeit with slides projected upside down. For Surrealists, such moments of rational collapse revealed pathways into unexpected creativity. Hallucination, error, and confusion allowed them to reach beyond logic or convention. Dalí’s near-suffocation was thus not a failure but a triumph, exposing the fragility of conscious control.

Nearly a century later, our contemporary era of Artificial Intelligence suggests Surrealism’s lessons may still be relevant. Anyone who has interacted at length with an AI language model has encountered its confabulations, fake links, spurious citations, and outright falsehoods—errors the industry euphemistically terms “hallucinations.” We ask AI for a straightforward answer, and it responds with a confident blend of truth and fiction. Many AI skeptics, along with people who tried early versions of LLMs and never returned, dismiss AI as fatally flawed because of these hallucinations. But hallucinations have existed long before AIs, indeed, they are everywhere we look.

Consider Dalí’s diving suit performance: as a historian of architecture, my grasp of surrealism is limited. In preparing this essay, I requested ChatGPT to identify compelling examples to open the essay with, and the AI highlighted Dalí’s incident. A web search for more details delivered the 2016 Guardian article “Dalí in a diving helmet: how the Spaniard almost suffocated bringing surrealism to Britain.” This is a random event in history. And yet, Dalí’s autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, tells a subtly different story: the artist says nothing about his air supply failing. Instead, he states that the lead shoes of the suit were extremely heavy and walking to the microphone to give the lecture was extremely difficult and tiring. He claimed he felt “faint and on the point of suffocating” and waved to his wife Gala and assistant Edward James to help him. They used the billiard cue to cut a slit between the helmet and the suit so he could breathe, then brought a hammer to knock off the bolts affixing the helmet to the suit. 1 The version of Dalí’s diving suit story described by ChatGPT—and echoed in The Guardian—was itself a hallucination that somehow became accepted as historical fact. It is, however, unclear where it came from. 2016 is long before LLMs were capable of being used as we use them today. Was it the product of a hastily written article? Is it a poorly-remembered first person account? Did Dalí embellish the moment himself in his autobiography? Did someone fabricate it for some purpose? Or did it just emerge, as things do?

I have long understood that the writing of history, even serious history, is a game of telephone. Memory, perception, and imagination intermingle, creating convincing yet fictitious narratives that shape beliefs, literature, and even history. Consider these iconic stories and quotes: George Washington’s cherry tree, Marie Antoinette’s notorious “let them eat cake,” or Voltaire’s defense of free speech, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” None of these individuals ever uttered these words. Such myths persist precisely because they reveal deeper cultural truths; they provide narratives we need to interpret and understand our world.

Hallucinations are surprisingly common in academic writing. I was inspired to write this essay in part because of my recent experience conducting research on early accounts of northeastern America and its beauty. Since I thought I knew where to turn, I was not using AI, instead I started with my bookshelf. In one of my favorite books, Jackson Lears’ Fables of Abundance, I found a compelling quote: “John Speede, in his Historie of Great Britain (1611), celebrated Oriana (the New World) as ‘the Court of Queen Ceres, the Granary of the Western World, the fortunate Island, the Paradise of Pleasure, and the Garden of God.'” And yet, Lears is mistaken. Speed—I am not sure where the extra “e” in “Speede” comes from—is clearly referring to Great Britain in the original. 2 Next, I looked at The Hudson. A History by Tom Lewis. The author cited a provocative passage by the early New Netherlander Adrian van der Donck, a Dutch lawyer and advocate for democracy, who, in his 1655 Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant (Description of New Netherland) wrote: “I admit that I am incompetent to describe the beauties, the grand and sublime works, wherewith Providence has diversified this land.” But Lewis, whose book was published in 2005, relied on a faulty, highly embellished translation from 1841. In a 2008 translation the line reads “I pray the indulgent reader to deduce from the above how fertile this land is and form his own judgment; as to myself, I confess to being unable to depict it or show it in writing, since in my view the eye alone, more so than the ear, is capable of comprehending it.” I thought it wise to double check so I quickly retrieved a scan of the 1655 text online and ran an excerpt through ChatGPT, which recognized the Dutch Blackletter text and suggested “I freely admit that I am not capable of portraying it fully or representing it in writing, as our judgment relies only on sight, and cannot assure the heart of its truth.” Not as elegant as the human translation from 2008, but confirming that the 1841 translation was embellished. I can’t fault Lewis for using the only translation available to him, it was the original embellishment that drew us both into the original reference. Unfortunately now it was useless for me. 3

Alas, I too, am no innocent in this. Take Blue Monday: Stories of Absurd Realties and Natural Histories, a book I know well, having co-authored it with Robert Sumrell. In explaining the title of the book, we refer to the pioneering post-punk band New Order’s 12″ “Blue Monday”:

In “Blue Monday,” the band achieved phenomenal media success, creating the most popular single of all time. But in their desire to become more digital–and hence more immaterial–than actually possible at the time, New Order retained graphic designer Neville Brody to make a die cut cover that would resemble the sleeve of a large floppy disk. The unique look won critical acclaim, but according to legend the most popular 12″ of all time cost the band 20 cents for every copy sold, ruining them financially but assuring their place in the regime of media. 4

This passage is the crux of the book, explaining the title and our collective drive to become more digital and immaterial. Except that I got it wrong. In a last editing pass, some neuron misfired and I substituted Neville Brody for the correct designer, Peter Saville. Robert let me know the moment he saw it, but it was too late, the book had been sent to the printers. As for the story about the financial losses, it may not be true either. While Factory records head Tony Wilson recounted it, he was known for exaggeration as well as poor record keeping.5

Sometimes, scholarly documents are fabricated out of thin air. Decades ago, I was in a graduate seminar on Renaissance urbanism at Cornell. I was assigned to explain the rebuilding of the town center of Pienza, the birthplace of Aenias Silvius Piccolomini, the humanist Pope Pius II. I recalled seeing marvelous plans of the site in Spiro Kostof’s introductory textbook A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals that showed the town before and after the intervention. I went on a lengthy paper chase, trying to figure out where these authoritative diagrams came from. There were no citations in the textbook and no credits for the plans. In the end, my hunch was that the author had a class in which students hypothesized what a pre-intervention condition might have looked like, produced plans, and included them in the book without noting that they were hypothetical reconstructions based on scant evidence.

Outright forgeries play a considerable role in history. In 1440, philologist Lorenzo Valla examined the Donation of Constantine, a fourth-century imperial decree supposedly granting sweeping temporal power to the Pope. The papacy cited it as their claim to power; kingdoms accepted it; scholars taught it as fact. But when Valla examined the Latin, he uncovered anachronisms impossible for Constantine’s time. The document was a forgery. Europe had built an entire political order on a historical hallucination. James Macpherson’s The Poems of Ossian took 18th-century Europe by storm, captivating Goethe and influencing Romanticism. Macpherson attributed these poems to Ossian, an ancient Gaelic bard. Only later did it become clear that Macpherson himself had largely composed these works. Or take the infamous Hitler Diaries, published in 1983 and swiftly authenticated by historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, only to collapse spectacularly under scientific scrutiny weeks later. Both examples show that scholarly hallucinations thrive not just on error, but on collective desires: readers hungry for heroic national pasts or sensational scoops. Where history isn’t enough, it seems we need to invent it.

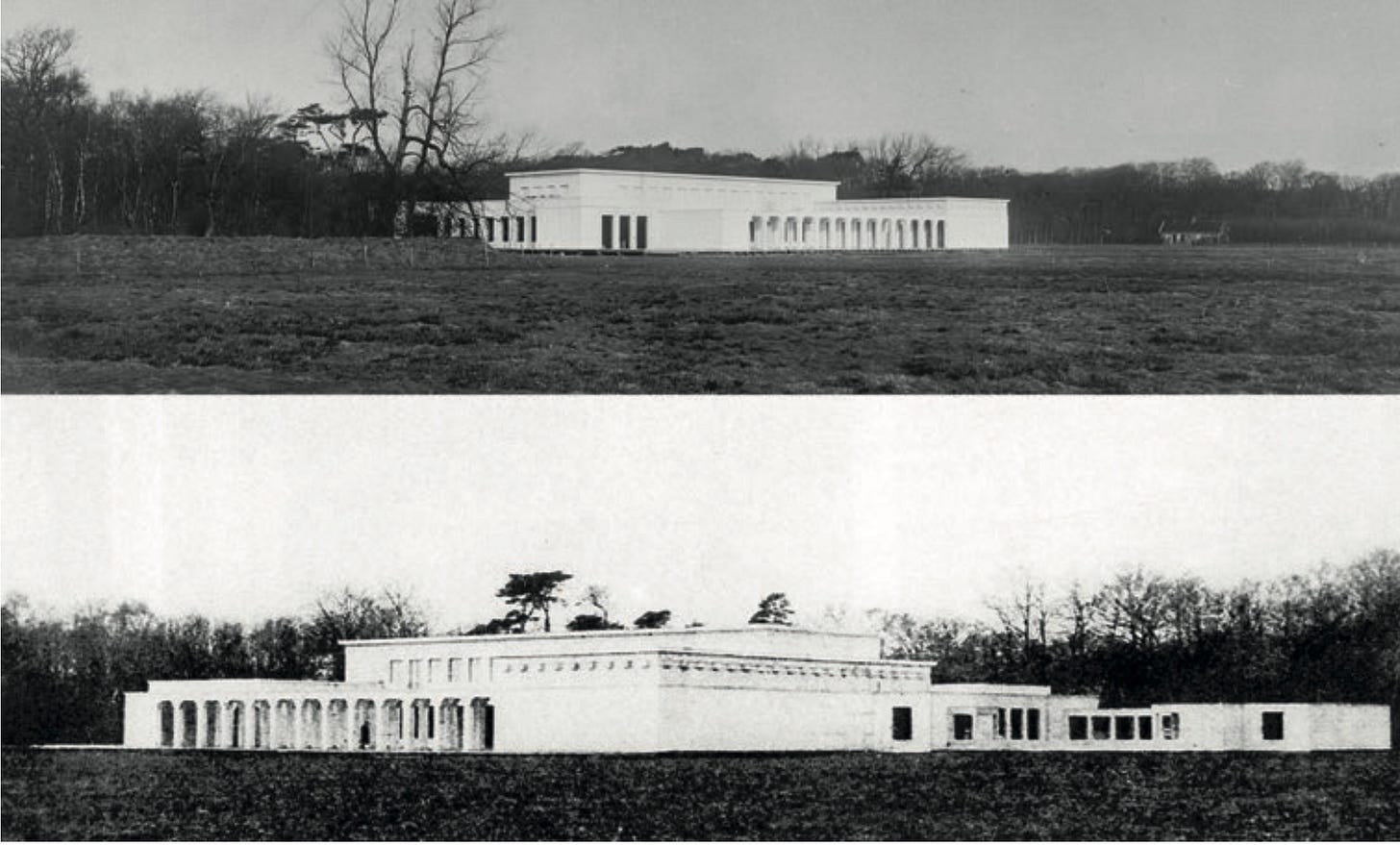

Museums certainly aren’t immune to this. Vast amounts of museum collections are composed of fakes and forgeries. In 2014, Switzerland’s Fine Art Expert Institute (FAEI) reported that at least half of the artwork circulating in the market is fake. Noah Charney, an art historian and founder of the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art, contends that approximately 95% of artworks displayed in museums are accurately attributed, suggesting that only about 5% may be misattributed or counterfeit. Still, things happen. Take, for example, the case of the Kröller-Müller House, which Ludwig Mies van der Rohe proposed. The story goes that Mies built a full scale mockup out of wood and canvas. It marks his first mature attempt to dismantle the traditional notion of the enclosed house and anticipate the open plan and fluid space that would define his later work. The house is exhibited in Philip Johnson’s 1947 Mies exhibition and reproduced in the catalog. Rem Koolhaas, in S, M, L, XL, however, says “What was weird was that when I asked Philip Johnson about the incident last year [around 1992], he said he had invented it. According to him, it had never happened. The photograph of the phantom house was a fake, he suggested. But who faked here? Whose fata morgana was this anyway?” Indeed, after looking at the image, it seems unimaginable that it isn’t simply drawn onto a landscape, a bit of mythologizing by Johnson. Perhaps, however, the fake was a fake. A web site for the Kröller_Müller Museum shows another image of the design, likely from their archive, however, this time the house looks far more real and the overlap of the tree branches seems hard to duplicate for Johnson, who was never much of a draftsman. Is the image from 1947 just taken from another angle? There seems to be a reasonable similarity in the trees in the background. Did Johnson perhaps draw in the more modernist wing on the right? Did he fabricate—whether due to poor memory or perhaps just capriciousness—the fabrication? Or perhaps Koolhaas, in search of a good story, came up with this.6

Unlike errors in print media, which remain localized to physical copies, digital mistakes can replicate across global networks, gaining authority through algorithmic amplification and citation indexing. Consider Rosalind Krauss’s Optical Unconscious, where a Freudian slip of the keyboard produced the phrase “treat of castration” instead of “threat of castration,” now faithfully reproduced in the MIT Press publication, a mistake that a typesetter would have noticed. 7 Or take the citation for “(Van der Geer J et al., 2010. The art of writing a scientific article. Journal of Science Communication 163(2) 51 – 59),” which has been cited in over 1500 academic papers to date according to Google Scholar. The essay, however, does not exist; it was a fictional example that escaped from a formatting template created by publishing giant Elsevier. 8 Scholars either forgot to delete the reference or cited the imaginary article without verifying it existed, inadvertently creating a collective hallucination propagated through databases and citation indices. Here, the parallel to AI hallucinations becomes particularly stark: scholars, like language models, confidently repeated nonexistent references simply because they seemed plausible. The ghostly paper highlights how easily we trust shared authority without scrutiny—an important lesson as we enter an era dominated by generative AI.

These errors—and countless others—reveal something profound. Human minds don’t merely seek truth; they also create it, often unconsciously bending evidence to fit narratives. The persistence of these illusions can distort entire disciplines, shaping how we perceive history, culture, and ourselves. Yet the errors also remind us how intimately creativity, wishful thinking, and factual missteps intertwine. Like surrealists embracing the subconscious or AI engines extrapolating beyond known facts, human culture thrives not only despite these hallucinations—but perhaps because of them.

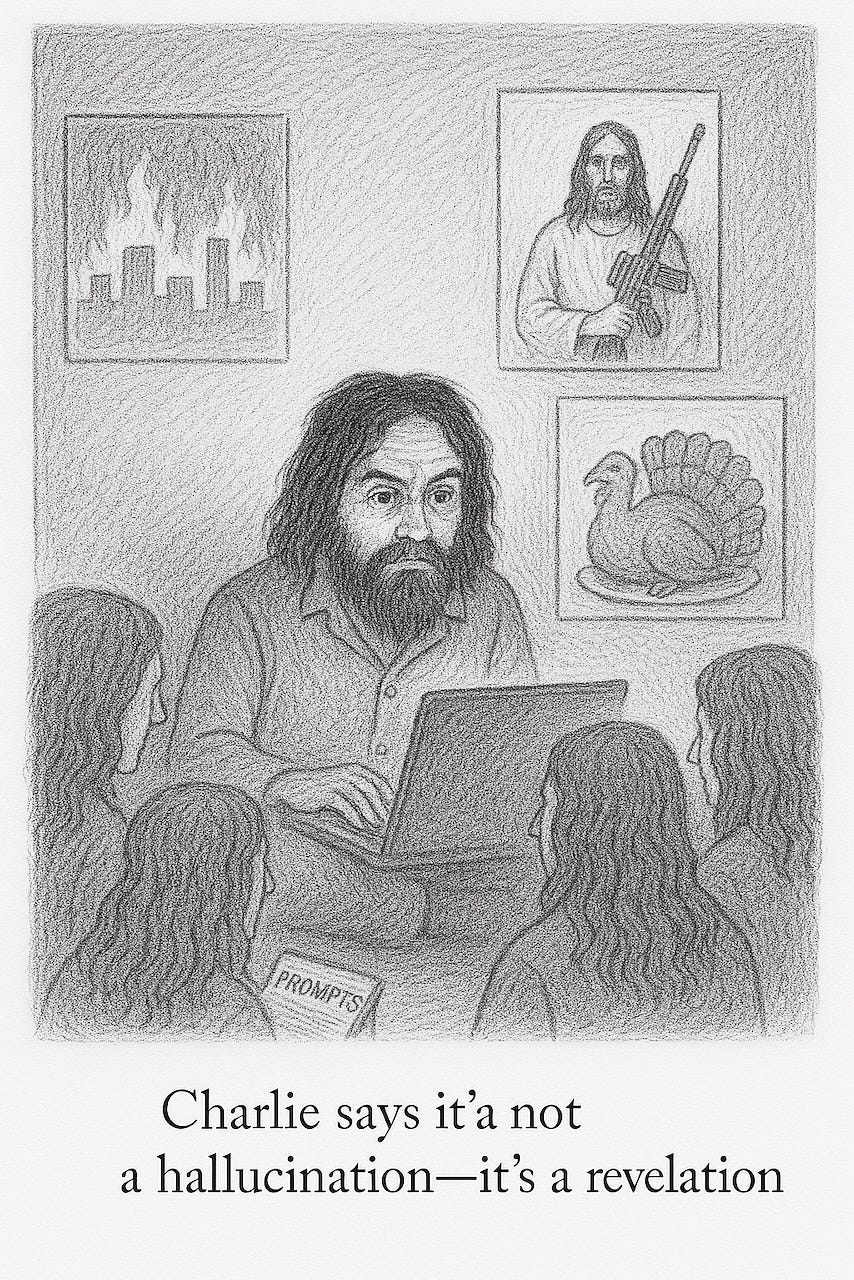

The typical explanation given for AI hallucinations is that at heart, today’s large language models—systems like GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini—are sophisticated pattern-recognition engines. Imagine a hyper-literate parrot that’s read every book in the library, capable of stitching together elegant sentences that sound authoritative, even insightful. But this parrot has no understanding of truth, context, or intent. Unlike traditional computing, which follows deterministic logic, LLMs operate probabilistically. Given the words “once upon a,” they will predict “time,” based on patterns learned from vast datasets. With a prompt like “In 1905, Einstein published a paper on,” the AI assesses billions of textual examples to choose the most statistically probable continuation (“special relativity”). But if the question ventures into obscure territory—a minor historical figure, niche cultural references, or poorly documented events—the model, optimized to provide helpful answers and rarely encouraged to say, “I don’t know,” will produce fiction to satisfy the prompt. The best-performing models, like GPT-4 or Claude 2, have been explicitly trained to recognize their limits and occasionally decline answering uncertain prompts, reducing—but not eliminating—fabrications. When a model makes up a hallucination, it’s akin to a human trying to sound knowledgeable at a cocktail party, confidently making up facts about obscure topics. AI mimics our own tendency toward myth-making.

But AI hallucinations aren’t just bugs; they’re symptoms of the underlying generative capability we value in them. If models rigidly stuck to memorized facts, they’d lose their remarkable ability to generalize, summarize, and invent. The same predictive flexibility enabling hallucinations allows AI to creatively interpret tasks—composing narratives, suggesting innovative ideas, or exploring hypothetical scenarios. Eliminating all hallucinations risks overly conservative models, timid and limited, good at trivia but poor at imagination.

But further, in December 2023, Andrei Karpathy, noted AI researcher formerly at OpenAI and Tesla, explained as follows.

# On the “hallucination problem”

I always struggle a bit when I’m asked about the “hallucination problem” in LLMs. Because, in some sense, hallucination is all LLMs do. They are dream machines.

We direct their dreams with prompts. The prompts start the dream, and based on the LLM’s hazy recollection of its training documents, most of the time the result goes someplace useful.

It’s only when the dreams go into deemed factually incorrect territory that we label it a “hallucination”. It looks like a bug, but it’s just the LLM doing what it always does.

At the other end of the extreme consider a search engine. It takes the prompt and just returns one of the most similar “training documents” it has in its database, verbatim. You could say that this search engine has a “creativity problem” – it will never respond with something new. An LLM is 100% dreaming and has the hallucination problem. A search engine is 0% dreaming and has the creativity problem.

All that said, I realize that what people actually mean is they don’t want an LLM Assistant (a product like ChatGPT etc.) to hallucinate. An LLM Assistant is a lot more complex system than just the LLM itself, even if one is at the heart of it. There are many ways to mitigate hallucinations in these systems – using Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) to more strongly anchor the dreams in real data through in-context learning is maybe the most common one. Disagreements between multiple samples, reflection, verification chains. Decoding uncertainty from activations. Tool use. All are active and very interesting areas of research.

TLDR I know I’m being super pedantic but the LLM has no “hallucination problem”. Hallucination is not a bug, it is the LLM’s greatest feature. The LLM Assistant has a hallucination problem, and we should fix it.9

In framing AIs as dream machines, Karpathy offers a provocative reimagining of a generative process akin to human creativity, in which meaning emerges through unforeseen associations, productive mistakes, and spontaneous invention.

Indeed, planned and unplanned deviations, mistakes, and hallucinations are a productive part of the creative process. In The Anxiety of Influence, literary theorist Harold Bloom argues that creative misreading is essential to literary evolution. Strong poets, he suggests, achieve originality by creatively misreading their literary predecessors. Bloom terms this “poetic misprision,” a strategic misinterpretation enabling poets to clear imaginative space within a saturated literary tradition. Misprision isn’t accidental—it’s a necessary act of rebellion, distancing poets from overwhelming influence and allowing them to develop their distinctive voices. This perspective reframes error not as failure but as generative necessity—what might appear as misunderstanding becomes the very foundation of creative innovation. Bloom demonstrates this through Milton’s deliberate misreading of classical tradition, transforming heroic narratives into complex psychological struggles in Paradise Lost, and through Wordsworth’s strategic reinterpretation of Milton’s elevated political voice into personal, introspective meditation. These creative distortions weren’t merely mistakes—they were essential evolutionary mechanisms that allowed new literary forms to emerge from existing traditions. Seen through Bloom’s framework, AI hallucinations might similarly represent not just errors to be corrected but potentially productive misreadings that open unexpected creative pathways beyond human convention. 10

Jacques Derrida, the founder of deconstruction, also recognized creative power in apparent errors, accidental fragments, and seemingly trivial textual moments. In Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles, Derrida famously analyzes a cryptic note discovered among Friedrich Nietzsche’s unpublished papers: “I have forgotten my umbrella.” Though seemingly inconsequential, this incidental sentence—an isolated fragment without context—opens new interpretive possibilities precisely through its ambiguity. Is the umbrella real or metaphysical? By resisting stable context and defying conventional reading, the phrase unsettles assumptions about coherent authorial intention. Derrida thus transforms Nietzsche’s trivial notation into a philosophical meditation on memory, forgetfulness, and textual uncertainty. The supposed error or accidental remark becomes generative precisely because it escapes closure, demonstrating that textual significance can emerge from absence, incompleteness, or apparent nonsense. This illustrates Derrida’s broader philosophical argument: meaning never resides simply in an author’s deliberate intent or in textual clarity alone but arises dynamically through interpretive engagement with ambiguity, uncertainty, and textual rupture. 11

The sciences, too, have flourished through productive error. The 18th-century phlogiston theory in chemistry—which proposed a non-existent element released during combustion—was entirely wrong, yet philosopher Thomas Kuhn noted how this incorrect paradigm “gave order to a large number of physical and chemical phenomena,” allowing scientists to organize observations until contradictions eventually led to oxygen theory. 12 Similarly, Johannes Kepler’s quasi-mystical belief that planetary orbits followed the geometry of nested Platonic solids drove him to analyze Mars’s orbit so obsessively that he discovered elliptical orbits and his three laws of planetary motion. Perhaps the most striking example comes from Albert Einstein. His cosmological constant—which he introduced to stabilize his equations because he mistakenly believed the universe was static and later abandoned, famously calling it his “biggest blunder”—has been essential for explaining dark energy and cosmic acceleration. The error contained within it a profound truth, one that Einstein himself couldn’t recognize in his lifetime. But the thing is that Einstein never actually called it his “biggest blunder”; the phrase was introduced in the autobiography of physicist George Gamow, who is notorious for embellishing and fabricating facts. 13

But these are outright errors. There are also cases in which scientists have taken their dreams and acted on them. René Descartes had three intense dreams that convinced him he should question everything he thought he knew, starting fresh from just one clear truth: that because he was thinking, he must exist. This approach—checking every belief carefully and trusting only what’s completely certain—became the starting point for modern science and philosophy. Chemist August Kekulé famously envisioned benzene’s ring structure after hallucinating a serpent swallowing its tail. Nobel Prize winner Otto Loewi dreamed of an experiment that would prove that nerve impulses were transmitted chemically, leading to the discovery of neurotransmitters. Finally, the periodic table of elements came to Dmitri Mendeleev in a dream. Except, in this case, once again, it didn’t happen. The first mention of the dream is forty years later. 14

Now, hallucinations in AI assistants are, as Karpathy states, a target of considerable investigation by AI labs and dramatic strides have been made to minimize their occurrence since the launch of ChatGPT-3.5. But LLMs are still, as Karpathy states, dream machines. Whether reading human or AI generated text, we need to remember the lost skill of critical reading and checking one’s sources. But if the progress goes too far, one day we may regret the loss of hallucinations.

For now, however, we still have AI hallucinations. And if, after reading all this, history seems like a tissue of lies, perhaps turning to the dreams of a machine for new ideas isn’t the worst thing to do? Turning back to the 1920s, surrealism sought to rupture conventional thinking by deliberately invoking dreams, chance, and subconscious imagery. Nearly a century later, a new creative practice—what we might call “the New Surrealism”—emerges from the collaboration between human imagination and AI hallucination. If LLMs are dream machines, their hallucinations are the computational equivalent of surrealist automatic writing—drawing connections across vast semantic fields without regard for factual constraints. This too can reveal new worlds hidden just beyond the edges of conventional thought in the collective unconscious. Is it coincidence that one of the hottest recreational trends in Silicon Valley’s AI scene is consuming magic mushrooms?

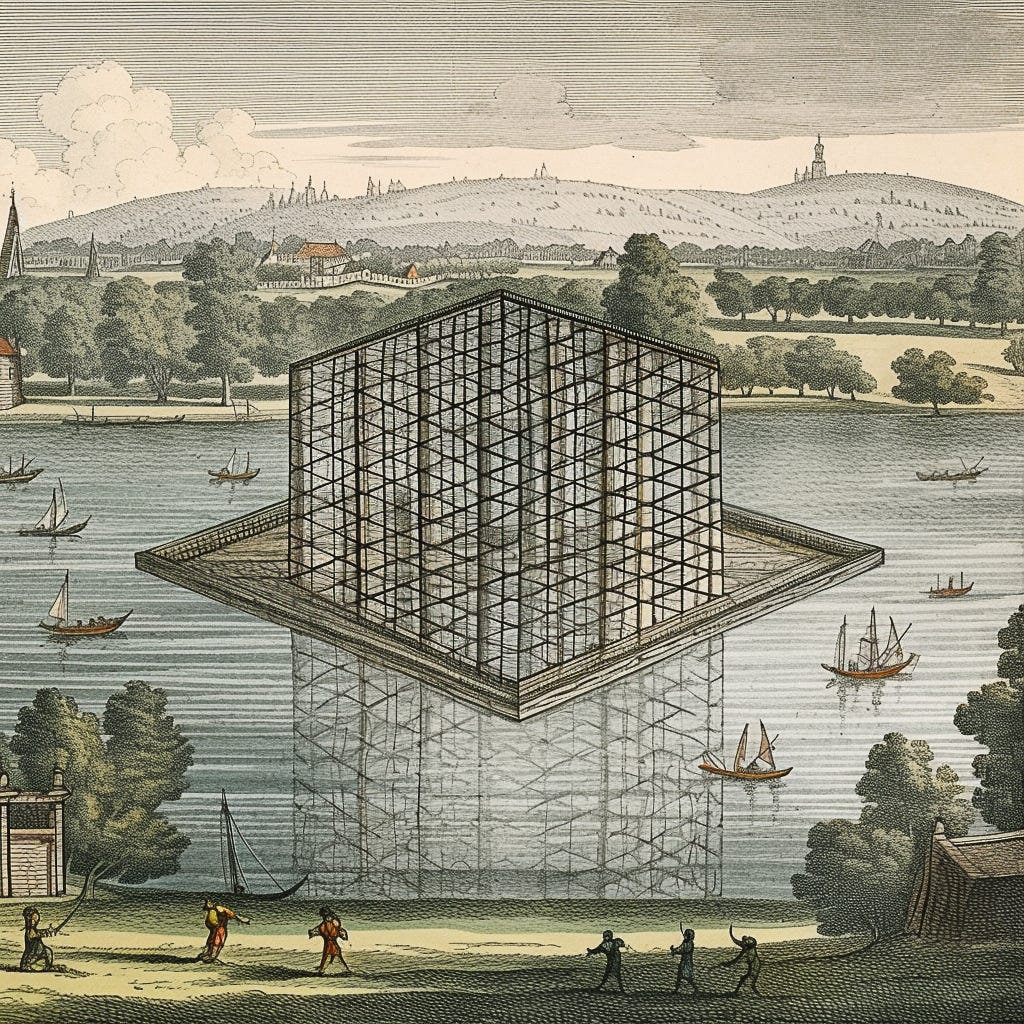

Take my friend architect and media theorist Ed Keller’s approach. Ed has described how for a few years now he has immersed himself nightly, often while drifting off to sleep, in working with AI image generations to create hallucinatory images deeply infused with architectural history, mythology, and ecological reflection. His invocation of Daphne—a figure of myth who transforms from human to tree—symbolizes humanity’s forced adaptation to the powerful external forces of artificial intelligence and the attendant ecological crisis. Ed’s creative method is surrealist in essence, blurring conscious and unconscious thought through a collaboration between human intent and machinic hallucination. Just as the original surrealism grappled with the unconscious mind mediated by industrial modernity, the New Surrealism emerges from dream-like dialogues with intelligences over the net, further reshaping human identity and perception.

My own studio work with AI image generators always engages with their hallucinations as creative contributions. Through extensive sessions with generative systems such as Midjourney or Google ImageFx, my practice critically engages with AI not as passive technology but as an active collaborator whose misunderstandings and apparent failures prompt me to develop the work in new directions.

In doing so, I uncover insights, exposing the underlying assumptions of authorship, originality, and authenticity embedded in our cultural frameworks. My projects, On an Art Experiment in Soviet Lithuania, Lost Canals of Vilnius, The Destruction of Doggerland, The Witching Cats of New Jersey, and Pierre Lecouille, Visionary Architect all take the guise of fictional histories. I should not have been surprised when an image from the first was poached and reposted without attribution by a viral poster, credits to me replaced by the words, “Not AI.” The two projects that I did not create fictional histories for, 20 subroutines for Humans Made By a Computerand Art and the Boxmaker addressed chance in the work of John Cage and the surrealist art of Joseph Cornell more directly. Just as early surrealism negotiated the unconscious mind reshaped by industrial modernity, my critical engagement with AI creates a contemporary surrealism born from the evolving dialogue between human creativity and networked, machine intelligence, continuously reframing identity, meaning, and artistic practice itself. Embracing rather than rejecting AI’s hallucinatory tendencies can transform creative practices, but it requires a serious effort, not merely a quick generation of political figures in the style of Studio Ghibli for viral posting.

In time, the New Surrealism may shape not only art but cultural criticism, literature, and education. We should teach students to recognize AI hallucinations not as defects but as invitations to critical inquiry and creative exploration. Scholars could intentionally leverage these errors to illuminate hidden assumptions or generate new interpretive frameworks. Our task, then, will not be to eliminate its hallucinations entirely but to thoughtfully manage, curate, and even nurture them. AI image generator Midjourney, for example, has a weird setting in which you can dial up its inventiveness—and rate of hallucination—as well as the ability to choose one’s model, including very old models that malfunction brilliantly.

André Breton described surrealism as “pure psychic automatism”—an attempt to bypass rationality by embracing random associations and visions. AI, guided by neural networks rather than neurons, performs a similar act of psychic automatism, weaving patterns without conscious control or intent. It generates surreal poetry, images, and narratives, sparking both anxiety and fascination. AI’s persistent hallucinations represent not only flaws but also opportunities to revisit surrealism’s radical experiments.

1. Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dover Books, 1993), translated by Haakon Chevalier, 345.

↩

2. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance:A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books ,1994), 27. The original text can be found online in text form at “The history of Great Britaine under the conquests of ye Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans. Their originals, manners, warres, coines & seales: with ye successions, lives, acts & issues of the English monarchs from Iulius Cæsar, to our most gracious soueraigne King Iames. by Iohn Speed.” In the digital collection Early English Books Online. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A12738.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. A scanned document is available at The History of Great Britaine Vnder the Conquests of Ye Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans. Their Originals, Manners, Warres, Coines & Seales: with Ye Successions, Liues, Acts & Issues of the English Monarchs from Iulius Cæsar, to Our Most Gracious Soueraigne King Iames (London: John Sudbury & Georg Humble, 1614), https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_History_of_Great_Britaine_Vnder_the/L9DE_ER5tAsC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

↩

3. Russell Shorto, “Foreword,” in Adriaen van der Donck, A Description of New Netherland, edited by Charles T. Gehring and William A. Starna, translated by Diederik Willem Goedhuys. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), ix.

↩

4. AUDC [Robert Sumrell and Kazys Varnelis], Blue Monday. Stories of Absurd Realities and Natural Histories(Barcelona: Actar, 2008), 80.

↩

5. Tonino Cannucci, “HOW WE MADE: NEW ORDER’S GILLIAN GILBERT AND DESIGNER PETER SAVILLE ON BLUE MONDAY,” Disorder and Other Unknown Pleasures, https://disordertc.wordpress.com/2016/03/10/how-we-made-new-orders-gillian-gilbert-and-designer-peter-saville-on-blue-monday/

↩

6. On fake art in museums see “Over 50 Percent of Art is Fake,” ArtfixDaily, October 14, 2014, https://www.artfixdaily.com/news_feed/2014/10/14/7319-experts-claim-fifty-percent-of-artwork-on-the-market-is-fake and Sarah Cascone, “50 Percent Art Forgery Estimate May Be Exaggerated… Duh,” Artnet News, October 20, 2014, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/50-percent-art-forgery-estimate-may-be-exaggerated-duh-137444 For the Kröller-Müller incident, see Rem Koolhaas, “the House that Made Mies,” S, M, L, XL. (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 62-63. See also Kröller-Müller Museum, “Ellenwoude, A Museum House of Wood and Sailcloth,” https://krollermuller.nl/en/timeline/ellenwoude-a-museum-house-of-wood-and-sailcloth

↩

7. Rosalind Krauss, The Optical Unconscious (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 172.

↩

8. Gareth Leng and Rhodri Ivor Leng, The Matter of Facts: Skepticism, Persuasion, and Evidence in Science(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020), 205.

↩

9. Andrei Karpathy, (@karpathy), “# On the ‘hallucination problem’,” X.com, December 8, 2023, 8:35pm, https://x.com/karpathy/status/1733299213503787018.

↩

10. Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

↩

11. Jacques Derrida, Spurs: Nietzsche’s Style (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979).

↩

12. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 99.

↩

13. Ernie Tretkoff, “February 1917: Einstein’s Biggest Blunder,” APS News, This Week in Physics History, July 1, 2005, https://www.aps.org/apsnews/2005/07/february-1917-einsteins-biggest-blunder and Rebecca J. Rosen, “Einstein Likely Never Said One of His Most Oft-Quoted Phrases,” The Atlantic, August 9, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/08/einstein-likely-never-said-one-of-his-most-oft-quoted-phrases/278508/.

↩

14. Philip Ball, “The true story of the birth of the periodic table, 150 years ago,” The New Scientist, February 26, 2019, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24132190-300-the-true-story-of-the-birth-of-the-periodic-table-150-years-ago/.

↩

Brilliant!