What did Vibe Coding Just do to the Commons?

Vibe coding is the single biggest transformation since ChatGPT 3.5, it is one of the biggest transformations since the dawn of computing. It will thoroughly transform Open Source. We are not ready.

As usual, you can read this at https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/what-did-vibe-coding-just-do-to-the-commons/. Please share this if you find it interesting.

I write a lot about art and architecture, landscape, and the impact of technology on culture, but I haven’t written about coding since the 1980s, when I sold my first article to Creative Computing magazine. Back then I was a high school kid, spending hours working in both BASIC and 6502 assembler on the VIC-20. I loved assembler, also dubbed “machine code.” It was a thrill getting so deep into a machine that you knew what was being shuffled from the microprocessor to the graphics chip or serial port to communicate with the world.

That feeling of getting inside the machine, making it do what you wanted—the hacker mindset—was also what the personal computer had promised. When the VIC-20 was released in 1981, William Shatner asked in the ads, “Why buy just a video game?” The personal computer was a complete break from the first mainframe era of the 1950s and 1960s, when computing meant submitting jobs to a priesthood and waiting for results hours later, and from the second mainframe era of the 1970s, when access was restricted to universities and corporations. For a high school kid, getting paid for articles—even ones that were never published—was an incredible feeling. But the joy of working with early computers produced a whole subculture. I was in a user group in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, and we would trade programs we had written, copying them to cassettes we had brought for the meetings. Joseph Vanhoenacker, who ran the group, was the director of Berkshire Mental Health, a lovely man perfectly willing to put up with a fifteen-year-old who wouldn’t stop talking about the possibilities computers created; like everyone else there, he shared the sense that everything would soon be different.

By 1990, everything was different, but our control over computers had quietly collapsed. Computers became genuinely useful. Everyone in college was writing their essays on computers, spreadsheets were used by businesses, you could balance your checkbook with Quicken—yet another form of disenfranchisement was underway. One fall I came back to university and the department secretary was gone. The faculty, who had come of age when using a typewriter was not considered appropriate for anyone hoping to be taken seriously as an academic, had somehow learned to type and her services were no longer needed. The first great wave of computer-driven white-collar job extinctions was starting, and women without college degrees lost a path to middle class. At the same time, people stopped writing their own software; it became something one bought instead. The complexity had scaled beyond what any hobbyist could manage. The machine was still technically programmable, but the barrier had risen out of reach. The first culprit was the Macintosh, released in 1984 and marketed as “a computer for the rest of us”—but “the rest of us” meant users, not programmers. The graphical interface hid the machine’s workings beneath icons and windows designed to feel intuitive, magical even. There was no prompt when you turned on the computer, no command line at all.

Arthur C. Clarke famously wrote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic; the Mac took that as a design brief. It succeeded by making you forget there was code underneath. The IBM PC and its clones kept a command line visible, but they were headed in the same direction. Soon the machine had become a beige box you operated, not a system you controlled. For my part, I had no patience for abstract math and even less patience for Pascal, the highly formal programming language taught in computer science programs. When I got a Mac in 1990, I briefly tried programming it, but the process was so unfamiliar and complicated that I gave up. I’ve returned to programming every now and then—for example, I wrote some Python code to drive my installation Perkūnas—but I never embraced coding the way I had in high school. I’ve always felt that as a loss. I’ve enjoyed my career, but this was a path I didn’t take, a whole branch of life gone. Moreover, for me, being a coder wasn’t just being a nerd, it was wrapped up in the punk-rock ethos of hacking. No polished interface can substitute for that.

Last October, at a workshop at Camp in Aulus-les-Bains led by Matthew Olden, I got a glimpse of that feeling again. Matthew—who, along with the other instructors Kathy Hinde and Carl Stone, I now count as a friend—is a musician and programmer who has spent twenty-five years building his own generative music software and releasing it online. In 2004, his band won an award for best left-field electronic act; the judges didn’t realize the tracks were generated by algorithms. At camp, the class he taught was on “vibe coding”: describing what you want in a prompt and letting an AI write the code for you. My interest was in programming Arduinos, which I had never done before, and within a day or two, using Claude Sonnet 3.5 and ChatGPT 4o, I was able to recreate the code for Perkūnas on the Arduino-like ESP32. Not bad, I thought.

When I got back to the US, I had a pressing need for a WordPress plug-in for my website so I could search for and export selected posts to text files. I used vibe coding to put one together. It brought down a staging version of my site a couple of times while I was debugging it, but overall it worked and it has continued to work flawlessly for the last year. But more advanced projects were beyond vibe coding’s reach. I wasted much of November trying to get an ESP32 to handle another project for a biennale, which turned out to be impossible because the hardware doesn’t support host mode audio over USB. Both ChatGPT 4o and Claude Sonnet 3.5 deceived me, pretending to have read online documentation when they hadn’t, getting into death loops, offering the same solutions over and over. I gave up on vibe coding and focused on working collaboratively with AIs on artistic work, a project that became Fables of Acceleration.

About two weeks ago, I noticed increased chatter on social media about how well Claude Code, an AI coding tool from Anthropic, works with the new Opus 4.5 model. I tried an experiment: create a version of Spectre, a desktop tank combat game I remembered from the early 1990s, written in JavaScript so it could run in a browser. The result was primitive, but after a half hour of coding and tweaking, it clearly worked.

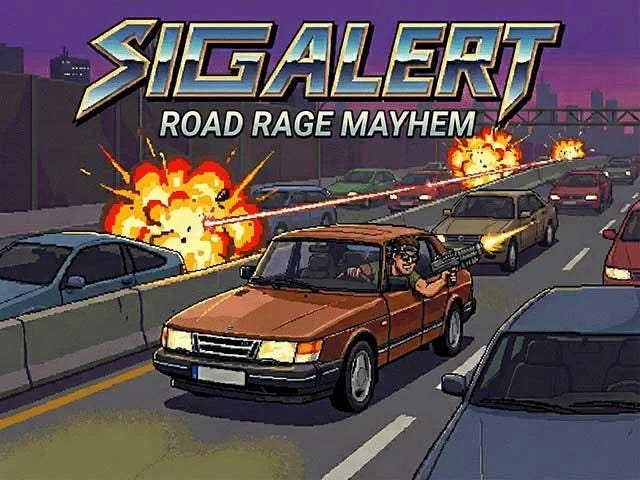

The most common critique of AI coding is that it merely regurgitates existing content—a critique that is itself regurgitated so reflexively, in such identical phrasing, that one wonders if the critics have considered the irony. Still, I thought it best to challenge the AI to reimagine that game as a 3D wireframe car shooter set on the Los Angeles freeway system. It worked immediately. I spent a day doing other things—writing, answering email, cleaning the studio, training Ajman the cat new tricks—checking in occasionally to offer feedback, never once touching the code myself. By the end of the day, I had an browser-based game I called Sig Alert, after the California Highway Patrol’s term for a traffic incident blocking lanes for thirty minutes or more. The game is a throwback to my experience living in LA between 1995 and 2005. Other drivers, gripped by road rage, are shooting at you; you shoot back. But there are civilians too, and if you hit too many of them, the police begin chasing you. Falling Down as a video game. If you kill more than ten civilians, the game announces “make mine animal style!”—a reference to In-N-Out Burger’s secret menu—at which point everyone starts shooting at you and you gain points from shooting everyone. I had Claude generate an 8-bit chiptune soundtrack inspired by Throbbing Gristle, Chris & Cosey, and Pink Floyd’s “On the Run,” while Google Nano Banana Pro produced a splash screen featuring my 1983 Saab. The game is deliberately rough since roughness is part of the aesthetic. Jen thinks a game about shooting others on the freeway is immoral. She’s not wrong.

A throwback cover and splash screen featuring my 1983 Saab 900S in the manner of a 1990s game cover for Sig Alert. That’s not me, I would have never worn a bandana around my head.

But my kid, now in game program at NYU, is going to be the game developer, not me. Sig Alert was just proof that vibe coding could work better now. I have a few art projects underway, and when those find a home, I’ll be glad to show them online. But I was also curious about just how far this could go. I decided to take up some old software that had fallen by the wayside, so I went to GitHub—the platform where most open-source software now lives, a combination of code repository and social network for programmers that has become the de facto infrastructure of collaborative development. I started with JPEGDeux, a simple Mac slideshow program that was itself a revival of JPEGView, a beloved piece of postcardware first released in 1991 when Macs ran on Motorola 68000 processors. When that was no longer viable, the JPEGDeux fork allowed the program to run on OS X, first on PowerPC and later on Intel Macs. Now, with a fourth chipset, Apple Silicon, Jpegview was finally orphaned. I had asked both Claude and ChatGPT to rebuild it last year, and while they had some success, there were basic issues we never got past, notably images did not scale to the full size of a window. The result felt like it was badly written by AI, because it was. This time I used Claude Code Opus 4.5 directly on a GitHub fork (a copy of the code that I cloned onto my own GitHub repository), and within a few tries had it running as well as it ever had. I added the ability to display videos, a file picker, and other enhancements in an afternoon. You can download the latest release here.

But this was still small beer. About ten days I caught a cold and it brought me down for about a week. When I’m sick, my brain is off as far as high-level processes like writing go, and even reading is no fun, but vibe coding was just my speed and surely better than doom scrolling. I thought about what would be the single most useful application to work on for my own workflow. I often get badly scanned PDFs of publications, and the downloadable, public domain books on Google Books often leave a lot to be desired. In the past I used a program called ScanTailor to do processing, but the process was clunky. It couldn’t take a PDF or export one after it was finished; it worked on a directory of images and that’s all it could output. Each run required substantial tweaking, and if the white balance was off, I’d need to go into Lightroom to fix the pages. Cleaning up a book often took more than an hour. Moreover, it’s hard to find a version that runs on Apple Silicon, and since updates are by volunteers, sporadic at best. Even the complexity of running it was daunting. When a new version was released, I would often have to go through a complicated series of steps to build it from source code. Often that failed and I didn’t know why.

Over the past week, I forked ScanTailor and modernized it substantially. I added PDF import and export—features I had long wished for—and updated it to run on Silicon Macs, taking advantage of new frameworks that exploit these chips’ capabilities. I redesigned the interface and added algorithms that determine whether each page should be black and white, grayscale, or color, keeping file sizes as small as possible. Now you give it a PDF and get a PDF back, often with no tweaking. What used to take me an hour takes minutes. I decided to get an Apple developer account so that I could distribute releases in .dmg files so anybody with a Mac could download and install the program. I’d be delighted if you tried it after downloading it from the above link and offered your feedback.

Clearly, the AI did not do this autonomously; I directed it, reviewed its work, caught its errors. The errors are relatively frequent but not a roadblock. I’m not a C++ programmer, but I have a sense for code from my early days and would likely have introduced just as many bugs myself—maybe more. Most critically: what would take a good programmer weeks takes an AI mere hours and, when you start to learn how it works you can have multiple instances running at once.

Strange Weather, my first module for VCVRack

As I got better at using Claude Code and more familiar with GitHub, I started other projects. I made Strange Weather, a module for the VCVRack music synthesis platform that produces modulation voltages based on four different strange attractors. Last night, I began working on an iPhone app that takes ambient sounds and turns them into generative audio pieces, much like the late, lamented RJDJ once did. And I have a portfolio/slideshow program for iPad in the works.

For the first time since the 1980s, I feel like I can do whatever I want—imagination is my only limit. Vibe coding is a bit like being a wizard, casting spells that make things happen. It’s also a bit like being a hacker, doing things to a system you don’t fully understand. I have buried the lede in this story but vibe coding is the single biggest transformation since ChatGPT 3.5, it is one of the biggest transformations since the dawn of computing. Let me be clear: someone with a good sense of how tech works but very little modern coding knowledge can, within a few days’ time write pretty much any program they want save for a AAA game. An age in which every mildly tech savvy person has their own personal suite of programs is upon us.

There’s an irony here. I argued earlier that the Mac took Clarke’s dictum about technology being indistinguishable from magic as a design brief, and that this was a kind of disenfranchisement: the code was hidden, the user reduced to operator. Now the magic has flipped. Instead of consuming software I can’t see inside, I am producing software, even if I don’t know how the production is done or what is in the code.

But I have anxieties about this sharing this work, even with you, Internet friends. There is a lot of hatred of AI out there. And since I don’t know the code, I don’t know how it will break things. What would the original contributors think? I doubt the current maintainers of ScanTailor would ever want to merge my changes back into their version, nor would I advise them to do so. AIs, for now, often create tangled “spaghetti” code, although I suspect this will improve dramatically in the next couple of years. But this brings us the problem at the heart of this essay, which is the culture of open source and the transformation it will face in the very near future.

There is a vast landscape of open-source software on GitHub, millions of repositories, and it is literally what the internet runs on. The browser you’re reading this in—Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge—is built on open-source code. So is Android. So are the servers that delivered this page to you, the databases that store your email, the encryption that protects your passwords. cURL, a tool for transferring data that most people have never heard of, is embedded in billions of devices: cars, televisions, phones, game consoles. A tiny utility called Log4j turned out to be running inside millions of systems when a critical vulnerability emerged in 2021; the maintainers, who were volunteers, got blamed for the crisis.

This leads us to the “commons.” The term comes from an old debate in economics. In 1968, Garrett Hardin argued that shared resources—common grazing lands, fisheries, forests—were doomed to destruction. Each individual farmer benefits from adding one more cow to the pasture, but if everyone does, the pasture is destroyed. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ became an argument for privatization: only ownership creates the incentive to preserve. Elinor Ostrom spent her career proving Hardin wrong. Studying communities around the world—Swiss alpine meadows, Japanese forests, Spanish irrigation systems—she showed that commons could be sustainably managed without privatization, but only with careful governance: clear boundaries, shared rules, monitoring, graduated sanctions for violations. She won a Nobel Prize for this work in 2009.

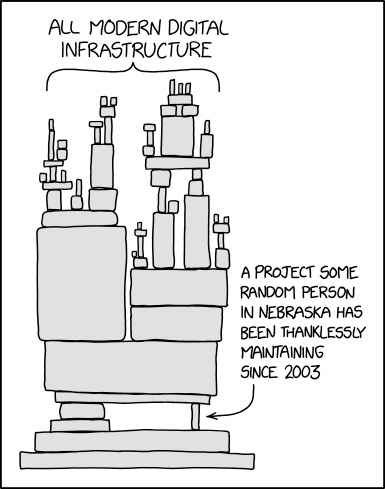

Open source was supposed to be a new kind of commons, one that escaped the tragedy entirely. Code isn’t consumed when copied; my use doesn’t diminish yours. But Ostrom’s insight still applies, just inverted. The scarce resource isn’t the code—it’s maintainer effort. The tragedy of the digital commons is not overuse but abandonment: projects that rot when no one tends them, vulnerabilities that fester, dependencies that break. The xkcd comic about all modern digital infrastructure resting on “a project some random person in Nebraska has been thanklessly maintaining since 2003” is barely a joke.

xkcd, “Dependency,” used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.

Most of those millions of repositories are dormant. Many never got anywhere in the first place, but then there are the ones in which maintainers burn out, find other jobs, have children, lose interest leaving behind code that is freely licensed, fully documented (or at least commented), with its complete history of changes preserved in version control. Anyone is legally permitted to copy it, modify it, redistribute it. And yet, until recently, this permission was largely theoretical. The freedom to modify code you cannot understand is not a practical freedom. It is like being granted access to a library in a language you do not speak.

Most projects die when their maintainer walks away. Others grow large enough to develop their own kind of inaccessibility—and then die anyway. This is, perhaps, an even greater tragedy. Again, personal experience is the best way for me to describe this. In 2005, I evaluated three competing content management system (CMS) for my website—Wordpress, Joomla, and Drupal. All had been released in the previous few years and initially they were competitive in terms of market share. Joomla was the most popular system in Europe and, for a time, the most popular CMS globally, but was too complicated and clunky for me. WordPress was, at the time, primarily a blogging platform and I wanted to run a whole website so I settled on Drupal. I used Drupal for thirteen years and increasingly grew to hate it and, sadly, dislike the attitude of the community that ran it. It comprised some seven hundred thousand lines of code, organized into subsystems so intricate that no single developer could possibly understand the whole. To become even minimally proficient—not to master it, just to work competently within it—requires years. Every time Drupal had a major update—usually every two years—my site would completely break and the more features I tried to add to it, the more time it would take to repair. My site’s layout had to be coded in the PHP programming language, design was in terms of increasingly complex code, but the leaders of the Drupal community insisted this was better for everyone. Nor could you sit still. As new updates rolled out, older versions were abandoned by the community and, lacking new security updates, became vulnerable to exploits. Learning how to update a Drupal site wasn’t easy. The community was not welcoming to people who didn’t contribute, and contributing was hard if you weren’t already part of the community. After Drupal released its eighth update, I was done with it. My friends who had developed sites with it were also glad to be rid of it. Joomla, I am told, had a similar trajectory. Today WordPress powers over 40% of all websites on the Internet; Drupal and Joomla, which were genuine competitors when I made my choice, have collapsed to a combined 3% of the CMS market and are still falling.

But such unwelcomeness was not arbitrary. Open-source communities developed particular cultures over decades, and those cultures had reasons for being the way they were. In the early days of shared computing, systems were fragile, resources limited, one careless user could bring down a machine everyone depended on. The sysadmins who kept these systems running developed a defensive posture that became encoded in community norms. The “Bastard Operator From Hell”—a satirical figure from early-nineties Usenet—captured something real: a sysadmin who treated users as “lusers,” sabotaged their work, hoarded knowledge, enforced arbitrary rules with sadistic pleasure. The satire resonated because it was barely exaggerated. The culture that emerged—the hazing, the gatekeeping, the suspicion of anyone who hadn’t paid their dues—was defensive in origin but became constitutive of identity. If difficulty is what marks you as a member of the tribe, then anything that makes the system more approachable cheapens what you achieved by surviving it. A recent blog post by Colin M. Strickland on Perl’s decline offers a case study: the language had a “significant amount of … ‘BOFH’ culture, which came from its old UNIX sysadmin roots” as well as “Perl IRC and mailing lists [that] were quite cliquey and full of venerated experts and in-jokes, rough on naivety, keen on robust, verbose debate, and a little suspicious of newcomers.” The people who had survived the brutality of early computing became invested in preserving difficulty as a mark of distinction. But the gatekeeping wasn’t only about identity—it was also governance, however crude. Ostrom showed that successful commons need boundaries, rules, monitoring. The hazing ensured that anyone modifying the commons understood what they were doing. The problem is that governance became identity, and the gates became ends in themselves.

So the barrier to participating in open source was double: technical complexity and social gatekeeping. The license said you could fork the code, take it, develop your own version. In practice, forking was expensive. You inherited the full complexity of the codebase, the technical debt, the implicit knowledge that existed only in the maintainer’s head. Successful forks were rare, usually occurring only when a community was large enough to sustain parallel development—LibreOffice splitting from OpenOffice, Illumos from OpenSolaris. For a single user who wanted one thing to work differently, forking was not realistic.

Today, the economics of forking are shifting. AI makes targeted modification possible for people who could not previously attempt it. You do not need to understand the entire system, just enough to make your specific change—and the AI can help you get that far. This is what I have been doing with ScanTailor, JPEGDeux, and code I could not have touched a year ago.

The collision this creates is real. Maintainers have given years, sometimes decades, of unpaid labor to projects the world depends on. They earned their positions by mastering difficulty, by surviving the gatekeeping, by understanding systems others could not. But users can now fork a project, modify it, bring dead code back to life—without permission, without apprenticeship, without going through the gates. Both groups have legitimate claims. The maintainers built the commons; the users were promised access to it.

The personal computer, in the 1970s and early 1980s, democratized access to computing: you could own a machine, use it for your own purposes, without institutional mediation. Open source, in the 1990s, democratized access to code: the licenses said you could read it, copy it, modify it, redistribute it. But reading and modifying required skills that most people did not have. The legal freedom was real; the practical freedom was not. That gap persisted for roughly forty years.

What AI coding tools do is close that gap. For the first time, the population that can modify software expands beyond the population that can write it. This is not an incremental improvement in programmer productivity. It is a change in who gets to participate.

One possible future is fragmentation: everyone maintaining idiosyncratic forks, no improvements flowing back to a common trunk. The traditional economics created pressure toward reconciliation; the cost of going it alone drove even rivals back together. If AI lowers that cost, the centripetal force weakens. Another possibility is relief: users who would have filed feature requests and bug reports now handle their own problems, reducing the burden on exhausted volunteers. A third possibility—the darkest one—is that the maintainers simply get routed around. Not rejected, just bypassed. The gate still exists, but nobody goes through it anymore. The years of unpaid labor, the careful stewardship of a codebase, the mass of implicit knowledge—none of it matters to the user who walked around.

I don’t know which of these will prevail, or whether the answer will be all of them at once, varying by project and community. But I want to be clear about the scale of what is shifting. Desktop publishing disrupted typesetters. Digital photography disrupted photographers. The web disrupted publishers. Each collapsed a barrier between conception and production, expanding who could make things. Software is more fundamental than any of them. Today software is infrastructure. Today software is how everything else runs. If the barrier to modifying it drops this dramatically, the consequences will take years to understand. What did vibe coding just do to the commons?