the Witching Cats of New Jersey (a Halloween Reprise), I of II.

Happy Halloween! A couple of years ago, I set out to make some AI-generated images that would look like a formal nineteenth-century portrait of an ancestor of our cat Roxy. This failed, but the results appeared rather evocative of ‘folk horror‘ and, after a few more iterations, I posted some “witching cats” to Instagram and some of my most valued friends asked that I produce more until I had a whole set of AI images as well as a backstory about the Witching Cats of New Jersey. Two years later, I am increasingly thinking that my recent work with AI imagery is done, but to bring it to a close I want to revisit all of my work with AI-generated imagery and update it before publishing it. This, then, is the first such effort. More on the way.

Note that this post is far too long for Substack. If you want to read the whole thing in one go, with a better experience, just visit https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/the-witching-cats-of-new-jersey/

The history of the European settlement of North America goes hand in hand with the history of occult practices—particularly witchcraft—on the continent. A large and unfamiliar land with an indigenous population that had recently died out under mysterious circumstances (now of course known to be largely due to disease brought by contact with Europeans) and in which esoteric movements were tolerated was fertile territory for individuals and groups with practices of worship at the edges of Christianity and even beyond. The very landscape itself seemed to encourage metaphysical speculation: vast forests that appeared and disappeared in the coastal mists, strange lights in the Pine Barrens (later attributed to bog gases but at the time thought to be spirit manifestations), and wildlife that bore little resemblance to European fauna. Even the most orthodox settlers found their religious certainties tested by what Cotton Mather would later call “the peculiar invisibles of the American sphere.”

Unlike Europe, where centuries of Christian orthodoxy had driven folk practices underground, the boundaries between accepted religion and forbidden knowledge remained porous in the colonies. While the Puritans of New England responded to this uncertainty with rigid control and occasional violent persecution, the middle colonies—particularly New Jersey—developed a more complicated relationship with the supernatural. Here, the practical concerns of survival often trumped theological purity. When crops failed or livestock sickened, even the most pious settlers might consult with indigenous healers or the “cunning folk” who had brought European folk magic traditions across the Atlantic.

This theological flexibility was particularly evident in New Jersey’s approach to familiar spirits—animals believed to serve as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual worlds. While Massachusetts ministers thundered against “the black dogs and cats that serve as Satan’s messengers,” New Jersey settlers developed a pragmatic mysticism. They accepted, and in some cases actively cultivated, relationships with animals that seemed to possess unusual abilities or awareness. This attitude would later prove crucial in the development of what became known as “the New Jersey school” of occult practice, characterized by its emphasis on animal intermediaries and its integration of indigenous, European, and African magical traditions.

Perhaps nowhere was this peculiar relationship between the material and spiritual worlds more evident than in the colony’s relationship with its felines. From the earliest days of settlement, observers noted something unusual about New Jersey’s cats—particularly the distinctive piebald or “tuxedo” cats that seemed to thrive in the colony’s peculiar atmosphere. These cats, according to multiple accounts, displayed an uncanny ability to appear in places they couldn’t possibly reach, to anticipate events before they occurred, and most disturbingly, to assume poses and attitudes that seemed almost human. As one anonymous diarist wrote in 1704, “Our cats here are not quite cats, nor yet are they something else—they exist in the spaces between what we know to be true and what we fear might be.”

While visiting the archives at Germantown College in New Germantown, New Jersey, I accidentally discovered their Witchcraft Collection. My research trip was focused on Paul Rudolph’s 1958 Science Center, one of his earliest explorations of sculptural concrete and a critical precursor to his later work at Yale. The building displays Rudolph’s emerging interest in complex spatial sequences and the manipulation of natural light, though here executed with more restraint than his later brutalist masterworks. I was particularly interested in the correspondence between Rudolph and the college administration about his decision to cantilever the laboratories over the surrounding pine forest, creating what he called “floating volumes of scientific inquiry.”

While examining the Rudolph papers in the college archives, I encountered a misplaced folder containing what appeared to be receipts for cat portraits commissioned from a “J. Rudolpha” in the 1780s. The Germanic surname variation had apparently led some student cataloguer to misfile these documents with Paul Rudolph’s papers. What caught my eye, however, wasn’t the name but the curious notations in the margins about the “particular qualities” of the cats being painted. The archivist on duty, Dr. Alistair Cailleach-Crone, noticed my puzzled expression and asked if I had stumbled upon “the cat papers.” What began as a simple inquiry about these mysterious receipts led to an invitation to view what Dr. Cailleach-Crone called “the full collection”—a vast assemblage of materials that would dramatically shift my research focus for the next several months.

The receipts, it turned out, were part of a much larger story—one that revealed an unexpected intersection between commerce and the supernatural in colonial New Jersey. As I explored the archives, a pattern emerged through merchant ledgers, ships’ logs, and personal correspondence, all pointing to a peculiar relationship between the region’s trading class and their feline companions.

Early New Jersey’s merchants viewed their relationship to the supernatural world as fundamentally practical. While their counterparts in Boston sought to cast out any hint of demonic influence, these pragmatic traders saw potential advantage in maintaining what one letter writer in 1772 called “a cordial relationship with the unseen.” Their ships plied dangerous waters, their warehouses faced constant threats from fire and vermin, and their ledgers balanced precariously between profit and ruin. In such circumstances, supernatural protection seemed less a luxury than a necessity.

Among all possible guardians against misfortune, cats held a special place in merchants’ estimation. Traditional maritime lore had long held cats to be harbingers of good fortune aboard ships, but New Jersey’s merchants seemed to attribute far more specific and unusual powers to their feline companions. The archives contain numerous accounts of cats that appeared to ward off storms, detect failing timbers before they gave way, and most remarkably, guide vessels through dangerous waters with uncanny precision. These abilities, combined with their more mundane but economically crucial talent for controlling vermin, made cats indispensable allies in maritime trade. It was perhaps inevitable that merchants would seek to honor—or perhaps curry favor with—these creatures through formal portraiture.

The fashion for commissioning portraits of cats began, according to account books in the Germantown Archives, with a series of successful voyages by the merchant vessel “Fortune’s Familiar” in 1763. The ship’s owner, Johannes Van Kattendijk, attributed his unprecedented run of good weather to the ship’s resident tuxedo cat, a notion that spread quickly through the merchant community of Perth Amboy. Van Kattendijk commissioned the first known “merchant’s familiar” portrait from J. Rudolpha, whose receipt book records not only the commission but also her growing unease with her subject. “The cat sits as no cat should,” she noted, “and fixes me with a gaze that knows too much.”

These early portraits followed conventional compositional formats—the cat positioned on a velvet cushion or before a painted ship—but subtle elements distinguished them from mere pet portraits. The cats’ eyes often seemed to follow viewers around the room. Their paws frequently rested on objects of occult significance: almanacs, strange instruments, or books whose titles remained deliberately obscured. Most notably, the cats’ shadows sometimes fell in directions that contradicted the painting’s primary light source.

Dr. Cailleach-Crone directed my attention to one particularly striking example from 1775: a portrait of a merchant’s cat named “Prospera.” The cat—a handsome black and white specimen—reclines with unsettling dignity on pink and crimson silk draperies aboard what appears to be a merchant vessel. Behind the subject, sailing ships dot the harbor at sunset. Strangely, a memento mori in the form of a skull is mounted in a classical-style display case, positioned so that it appears to gaze directly at the cat. The cat, in turn, meets the viewer’s eyes with an expression of self-possession.

“Note,” Dr. Cailleach-Crone said, “how the artist has captured not just the cat’s physical form, but its evident awareness of its own status. The skull, the silk, the ships—these aren’t just symbolic elements of merchant wealth. They’re statements of power. The cat isn’t merely being portrayed in its owner’s setting; it’s being shown as the true master of these domains.” He pointed to the way the cat’s black fur seems to absorb light while its white chest almost appears to glow with its own inner luminescence. “The merchants may have commissioned these portraits, but something in the artist’s handling suggests they knew who—or what—they were really serving.”

The painting’s original invoice, preserved in the Rudolpha folder, lists an unusually high price of 15 pounds, with a cryptic note: “Additional charge for subject’s insistence on specific and unpleasant requests. Artist requests no further commissions of this type.” J. Rudolpha’s account book, which spans the years 1763-1779, shows a disturbing and gradual shift in her terminology. Early entries refer simply to “cat portraits,” but later ones mention “capturing their true aspect” or “revealing their nature.” Her final entry, dated just before her disappearance in the winter of 1779, reads simply: “They are not what we thought. They never were.”

Benjamin West, visiting New Jersey in 1771, described the merchants’ cats as “possessed of a peculiar quality of stillness, unlike the general nature of their kind.” When commissioned to paint such a portrait himself, West found the experience unsettling. As quoted earlier in his notebook: “Damned cats and their owners. To the devil with them! These Jersey brutes love their animals but to have them sit for you would try any man’s patience. And half do seem to be possessed by the devil. I will never lose the scars from these accursed creatures, all claw and fang.”

Less well-known is West’s letter to his wife, discovered in the Germantown Archives, where he adds: “The merchant Kattendijk’s beast sat perfectly still for three hours, never blinking, never shifting. When I attempted to paint its eyes, my hands shook so severely I was forced to stop. The creature knew what I was about, of that I am certain.”

The archives contain several dozen examples of these merchant portraits, though evidence suggests many more were destroyed in the early 1800s when religious revival movements swept through the region. Those that survive share certain unsettling characteristics: the cats are predominantly black and white, their poses suggest human intelligence, and most disturbingly, their paws often appear unnaturally articulated, more like human hands than feline appendages. Dr. Cailleach-Crone pointed out that in several paintings, these prehensile paws are shown manipulating objects with an anatomically impossible dexterity. A ledger from 1780 lists standard prices: “For a simple cat portrait, 5 pounds. For a cat portrait with special qualities made apparent, 12 pounds. For a cat portrait with full powers manifest, price upon discussion and proof of worthiness.”

The religious revivals of the early 1800s drove many wealthy New Jersey families to destroy or conceal their cat portraits, marking the end of the formal merchant period. Yet rather than eliminating the practice, this suppression merely forced it to evolve. As Dr. Cailleach-Crone noted while showing me a series of small wooden panels from this period, “The cats simply found different ways to be seen.”

The transition is perhaps best documented in the curious case of the Van Kattendijk portraits. In 1801, following a series of fiery sermons at Perth Amboy’s First Presbyterian Church condemning “commerce with familiar spirits,” the Van Kattendijk family publicly burned their collection of cat portraits in what the local newspaper called “an act of Christian redemption.” Yet within a decade, similar images began appearing in the Pine Barrens, painted on boards scavenged from shipping crates still bearing the Van Kattendijk merchant mark.

The Pine Barrens proved fertile ground for such supernatural resurgence. This vast stretch of sandy soil and pitch pines had already garnered a reputation for strange occurrences, most notably the Leeds Devil (later known as the Jersey Devil). Its scattered communities of charcoal burners, glass makers, and bog iron workers developed their own distinctive folklore, mixing European traditions with local innovations. Here, away from coastal prosperity and religious orthodoxy, the witching cats found new expression in the hands of self-taught artists.

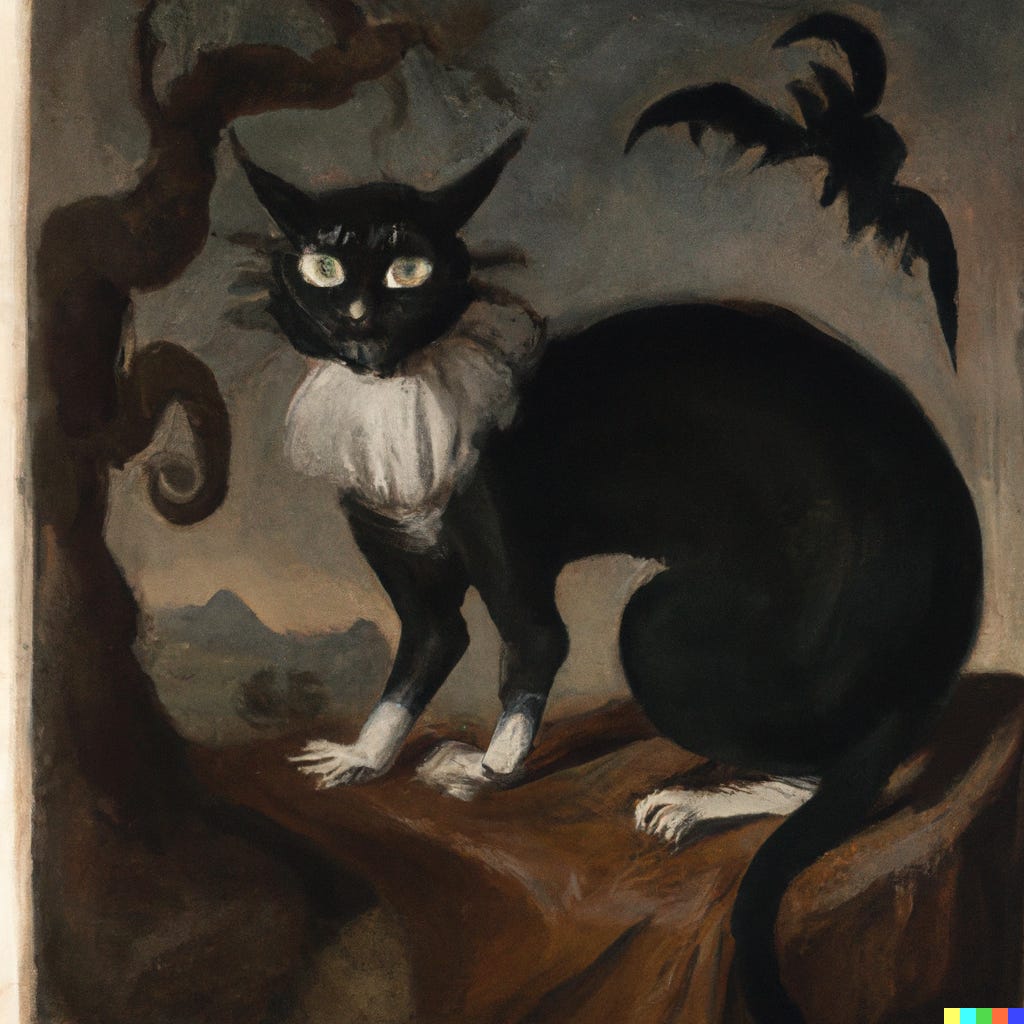

By the 1820s, the Witching Cats found a resurgence in the work of self-taught artists in the Pine Barrens, whose crude but powerful paintings captured something their more polished predecessors had perhaps feared to express directly. These artists, working with whatever materials they could obtain—often house paint on reclaimed wood—created images that abandoned any pretense of conventional felinity. Instead, they showed the cats as they perhaps truly were, or as the artists believed they had glimpsed them in the deep woods or through cabin windows on moonlit nights.

Artist Unknown, New Jersey 1820s, Germantown College Archives.

The Germantown Archives contain several striking examples. One shows a tuxedo cat in an unsettling upright pose, its unnaturally elongated arms ending in distinct human hands with articulated fingers. The figure is dressed in what appears to be a white shift or nightgown, but it’s the eyes—rendered in burning yellow—that draw and hold the viewer’s attention. Another depicts a similar creature beneath a crescent moon, wielding what appears to be a staff or scythe. In the foreground, a tombstone or marker bears the cryptic inscription “LOY.” The landscape behind it suggests the rolling hills of Sussex County, though rendered in a fever-dream intensity of greens and reds.

Perhaps most disturbing is the image of a cat in formal evening wear, complete with hat, raising a glass in what can only be described as a hideous mockery of human social ritual. The gesture seems deliberately calculated to unsettle—not a mere imitation of human behavior but rather a pointed demonstration that such behaviors can be performed, and thereby rendered hollow, by something that understands but does not share our nature. Dr. Cailleach-Crone noted that its other hand is positioned in a gesture found in several 17th-century grimoires, though he refused to specify its meaning.

These paintings often incorporate subtle symbolic elements—pointed ears that echo church steeples, tails that form binding symbols, whiskers that trace out protective circles. But it’s their directness that proves most disturbing. As one contemporary observer noted in a letter preserved in the archives: “These are not portraits of cats pretending to be human. These are portraits of something wearing a cat’s shape with increasing impatience.”

The most notorious piece from this period shows a cat mid-transformation, its white-gloved hands splayed to display red finger-length claws, its yellow eyes containing terror. The painting was reportedly found nailed to a Pine Barrens chapel door one morning in 1832, the nails driven through with such force they penetrated the oak boards completely. No artist ever claimed credit for the work.

Email length limit reached … see the rest at https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/the-witching-cats-of-new-jersey/