The Phantasmagoria of the Landscape: Japanese Gardens in America

After two posts on art and AI and two on economic transitions in the age of AI, it’s time for a lengthier Florilegium essay. If most of those posts are on native plants, this one is instead inspired by my trips to Japan where we saw the amazing gardens there as well as my inevitable disappointment at seeing the simulations back in the United States, particularly the greatly reduced efforts that appear in our suburban gardens.

At some point—not in the next missive from this Substack and perhaps not even in the next post for the Florilegium—I will set out my first attempt at a coherent aesthetic philosophy based on the native plants of the Northeastern American seaboard and what Lawrence Buell dubbed “The [American] Environmental Imagination.”

As always, you may read the post on my site, https://varnelis.net/the-florilegium/the-phantasmagoria-of-the-landscape-japanese-gardens-in-america/ Don’t expect the footnote links to work on Substack as they are hard coded to my site.

Also, I ask only that if you appreciate this post, please spread it widely.

Last April, we spent a week in Tokyo and Kyoto during Sakura, the cherry blossom season. The bloom’s unpredictability makes timing difficult, but our visit coincided fortuitously with spring break. Our son, newly admitted to NYU to study video game development, wanted to visit the epicenter of gaming. Shortly after arriving, we walked to Shinjuku Gyoen Park, where blossoms formed canopies over gravel paths, their fallen petals gathering at tree bases and along the edges of still ponds. In Japan, Sakura transcends visual delight to embody mono no aware, a sensitivity to life’s ephemeral nature central to both Buddhist philosophy and Shinto practice. Hanami, the viewing of cherry blossoms, thus becomes more contemplative ritual than casual custom—an affirmation of beauty’s inevitable passing.

During our visit, we made the journey to Saihō-ji in Kyoto (the opening image in this essay), a Rinzai Zen temple founded in the 8th century but redesigned in 1339 by the renowned priest Musō Soseki. Unlike gardens designed primarily around seasonal blooms, Saihō-ji (known today as Kokedera or “Moss Temple”) offers a different approach to the garden experience. Before entering, visitors must copy sutras by hand, a meditative practice preparing the mind for deeper engagement. The garden, now carpeted with over 120 moss varieties, wasn’t planned this way—Soseki originally created Japan’s first dry landscape garden (karesansui) with white sand and green pines—but emerged naturally after floods and neglect transformed the landscape. The garden doesn’t aim to dazzle but to engage deeply, creating a space where the slow work of time becomes tangible through surfaces that change with moisture and light.

This profound attention to natural processes stands in stark contrast to common American garden practices. Unlike my neighbor who uses a gas-powered leaf blower to sanitize his hardscape, Japanese gardens intentionally accommodate change. Fallen petals remain visible for a time underneath cherry trees. Bare branches become essential compositional elements. Moss advances gradually across surfaces. Rather than masking natural cycles, garden caretakers embrace them, creating environments where visitors experience time’s passage directly.

My experiences in Japan prompted deeper reflection on how Japanese garden aesthetics are frequently misinterpreted in American adaptations. I planned to document these thoughts for The Florilegium, but such reflections were abruptly overshadowed by a stark personal encounter with mono no aware: during our train ride to Narita, we received a call that our cat Roxy was dying. She passed away the next morning with us by her side. This spring, it is time to revisit the blooms—and set down my reflections. Sakura season has long passed in Tokyo, but in northern New Jersey, the trees at Branch Brook Park—home to more Japanese cherries than even the National Mall—are just past their peak. In Japan, these bloom dates have been recorded since the 8th century, forming the world’s oldest phenological dataset, now critical to climate science. In a previous essay for the Florilegium, “On Keeping a Phenological Diary,” I wrote about such seasonal tracking across various cultures. This year, I walk around the garden daily and look for changes, recording them. I worry about what I see: the aftermath of a four-month drought last fall, heavy browse from starving deer, a sudden cold snap in April. My Maidenhair ferns (Adiantum pedatum) are late—other plants they normally outpace are already leafing out. My Foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia) is sluggish. Many of the young trees I planted last year are taking too long to show signs of life. Is it Vascular Streak Dieback, the latest horror to appear in our area? Still, taking these notes grounds me. It connects me to temporal rhythms larger than my own—to the pattern of return and disappearance, presence and loss.

Returning to Saihō-ji, I was struck by the beauty of the place—it was clearly artificial and yet natural in a way few Western gardens are—and I found myself reflecting on how superficial the American idea of Japanese landscape is. What we’ve adopted are fragments divorced from context—isolated specimens and decorative elements without the underlying philosophy or ecological sensitivity that gives them meaning. Even when Americans claim to embrace Japanese garden philosophy, it often rings hollow—filtered through the commercialized lens of wellness retreats, corporate mindfulness seminars, and pop-culture interpretations of Zen that bear little resemblance to centuries of authentic practice. The flowering cherries that frame the Washington Monument, the Japanese maples that punctuate suburban yards, the Kousa dogwoods that have replaced their American cousins—these botanical immigrants have so thoroughly colonized our landscape that we scarcely recognize them as foreign. But looking at the journey from Shinto shrine to suburban development reveals a complex history of cultural fascination, diplomatic exchange, ecological disruption, and philosophical misunderstanding.

The introduction of Japanese gardens to the American aesthetic begins in Philadelphia in 1876, at the Centennial Exposition, the first World’s Fair held in the United States. The Centennial Exposition featured numerous wonders: the Corliss Engine symbolizing the triumph of steam power, gadgets like the telephone and the typewriter, the debut of foods like Heinz Ketchup and Hires Root beer, a Women’s Pavilion, showing women’s contributions to knowledge, art, and industry and the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America’s “Total Abstinence Fountain” featuring a giant Moses as a centerpiece. Amidst all this technology were pavilions sponsored by foreign nations to showcase their accomplishments. The United Kingdom showed not only its industrial accomplishments, but also designs like Owen Jones and Christopher Dresser, Germany showed precision engineering and a 50-ton cannon, while France showed off luxury goods and high design alongside mechanical devices.

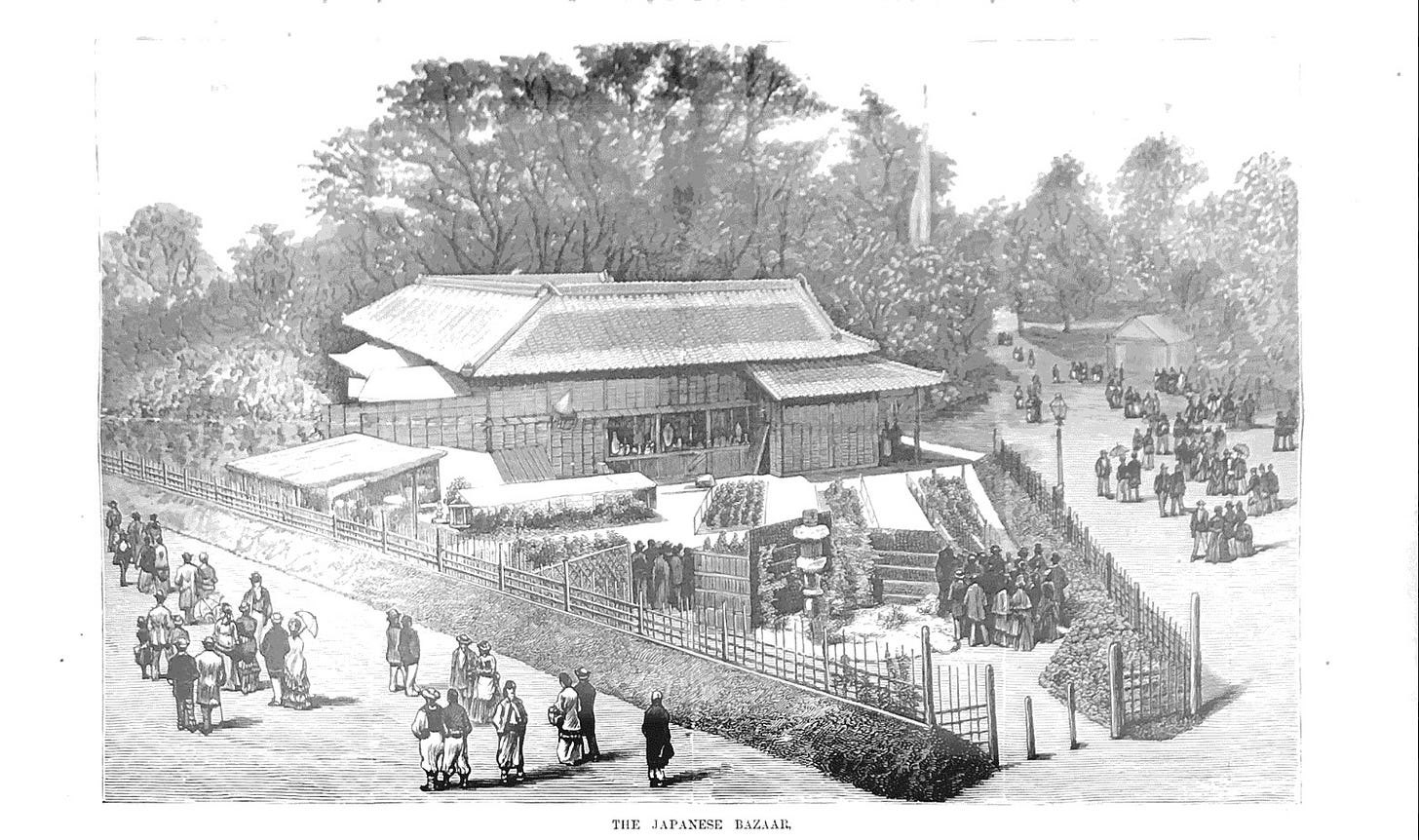

The most stunning exposition, however, was the Japanese Commissioner’s Building as well as a Japanese Bazaar and garden, unlike anything Americans had seen before, with their curved-roof pavilions, delicate teahouse furnishings, manicured paths, and living botanical curiosities. With the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan had reopened to the world after centuries of Tokugawa isolation and sought to assert its cultural presence and gain international recognition. Japan’s display at the Exposition was thus a strategic act of aesthetic diplomacy, which the country used to distinguish itself from a generalized “Orient” perceived to be in decline. The pavilion and garden suggested that Japan, unlike China or America, was both ancient and modern, exotic but disciplined. The local audience responded with enthusiasm. Of the Commissioner’s Building, contemporary observers deemed “the finest piece of carpenter work ever seen in this country.” The Atlantic Monthly captured the prevailing sentiment when it observed that the Japanese designs made everything else at the exhibition look “commonplace and vulgar” with their clean lines and simple elegance. A bazaar building sold porcelain, lacquerware, textiles, and decorative objects that embodied Japanese aesthetic principles. Most noteworthy was America’s first authentic Japanese garden, that challenged Western notions of landscape. Thompson Westcott’s Centennial Portfolio, which started out its entry on the Japanese Bazaar by saying “The Japanese are certainly the Yankees of the Asiatic continent” described the garden:

The little piece of ground which surrounds this building has been enclosed and fixed up in Japanese garden style. The flower-beds are laid out neatly and fenced in with bamboo. Screens of matting and of dried grass divide the parterres. There is a fountain guiltless of jet d’eau from which the water trickles. At the southern entrance a queer-shaped urn of granite on a pedestal, shows marks of great age, being weather-worn and dilapidated. It must have done garden service years before Perry opened Japan to the Western nations, and it was carved by Niphonese who had never seen a foreigner, and who never could have expected that their work would be transported thousands of miles to be inspected by millions of strangers. The garden statuary is peculiar. Bronze figures of storks 6 to 9 feet high stand in groups at certain places, and a few bronze pigs are disposed in easy comfort in shady places.

The legacy of this introduction to Japanese culture continues in Shofuso, a Japanese cultural center and garden built in 1953 on the site of the Japanese garden in 1876 Centennial Exposition, but it is not the same as the one built in 1876 (curiously the house was originally installed at the Museum of Modern Art in 1954). 1.

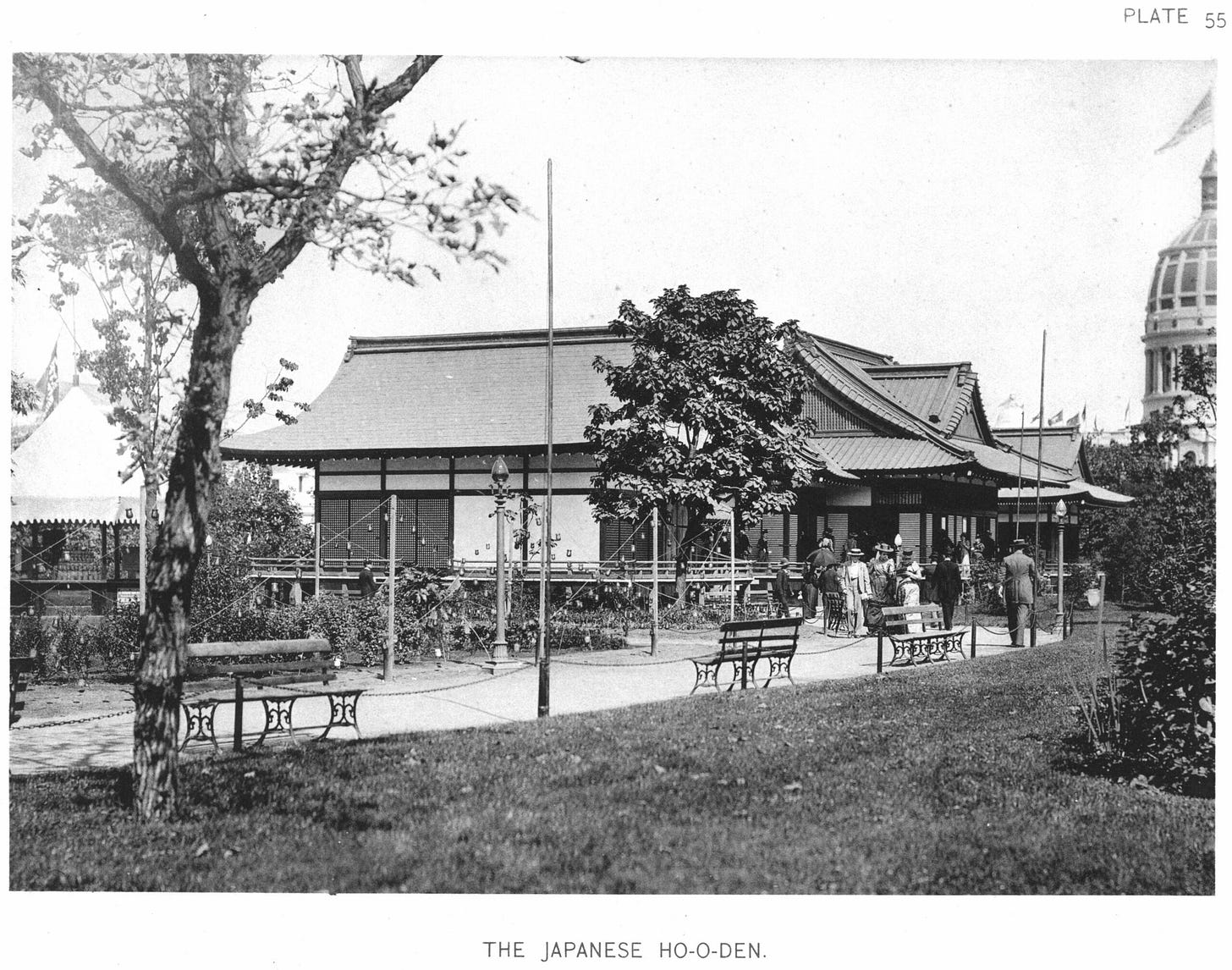

Other fairs followed. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Japan mounted a far more ambitious display: the Hō-Ō-Den, or Phoenix Hall, an architectural pavilion modeled on a 10th-century temple, constructed on Wooded Island in Jackson Park. The design, by architect Masamichi Kuru was a deliberate cultural projection to assert civilizational parity. Inside, curators including Okakura Kakuzō arranged artwork, objects, and furnishings to present Japan as refined, orderly, and timeless, a counterpoint to the noisy spectacle of the fair’s neoclassical White City. Thousands crossed the bridge to Wooded Island to experience what the Chicago Tribune described as an oasis of calm. Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as Charles Sumner Greene and Henry Mather Greene (Greene & Greene of Pasadena) visited, the latter stopping by while moving from Boston, where they had studied, to Pasadena. Japanese design was not only admired—it began to shape American modernism.

The 1894 Midwinter Exposition in San Francisco featured a “Japanese Village” so popular it became permanent. Landscape designer Makoto Hagiwara, who had helped install it, convinced city officials to let him expand the site. The result was the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park, the first public Japanese garden in the United States. Hagiwara spent the rest of his life tending and enlarging the garden, importing teahouses, sculpted pines, and stone lanterns. Visitors marveled at dwarf trees and koi ponds. The garden became both spectacle and sanctuary—a transplanted aesthetic shaped as much by the American desire for the exotic as by Japanese craft.

The Japanese garden aesthetic spread quickly from world’s fairs into books, nurseries, private estates, and botanical institutions such as the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Lafcadio Hearn’s essays from Japan and articles in The Century and Harper’s brought tales of moss gardens, stone basins, and lantern-lit evenings to an upper-middle-class readership eager for cultural sophistication. Wealthy collectors commissioned “authentic” tea houses and gardens for their grounds. Henry E. Huntington’s estate in San Marino, California, boasted one of the most elaborate examples. On the East Coast, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden established its Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden in 1915, designed by Takeo Shiota. Combining a pond, hills, wooden bridges, lanterns, and native Japanese plantings, it was one of the first Japanese gardens in an American public garden and remains among the most historically significant. Unlike many contemporary imitations, Shiota’s design was rooted in traditional principles and carefully attuned to site, season, and spatial movement, however, it also helped cement an emerging consensus among American garden designers that Japanese garden design could be achieved through the use of tropes such as Torii gates, wooden bridges, lanterns, and that it needed to rely on Japanese plants outside of their native context.2.

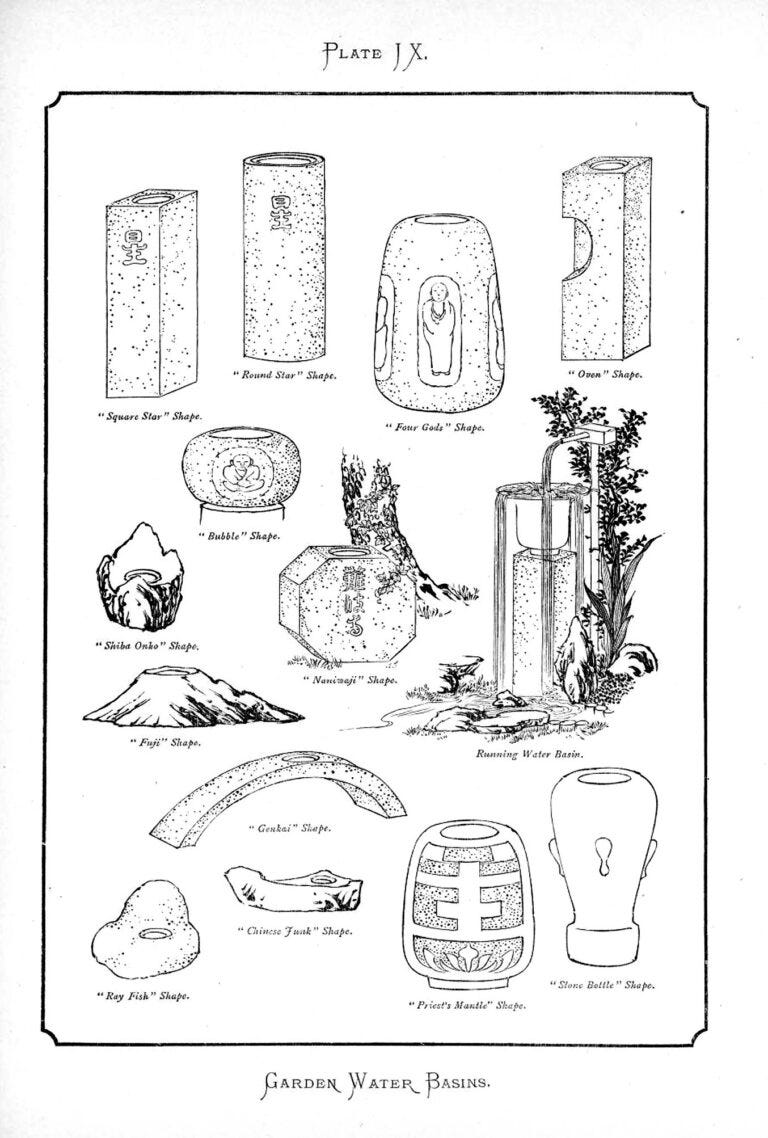

This reduction of Japanese gardens to their visual elements was intellectually formalized in the West by Josiah Conder’s influential 1893 book Landscape Gardening in Japan. Conder, a British architect employed by the Meiji government from 1877 to 1888—notable also for teaching Masamichi Kuru of the Hō-Ō-Den—documented Japanese garden traditions with unprecedented thoroughness for Western readers. Despite his technical rigor and apparent admiration for Japanese aesthetics, Conder’s approach overlooked the spiritual and philosophical essence of these gardens. His text meticulously catalogs decorative elements—stone lanterns, stepping stones, garden bridges—while presenting them as isolated objects rather than integral parts of a coherent philosophical system. In the book’s nearly 300 pages of detailed observations and measurements, garden elements are classified according to rigid typologies: “Eight Views,” “Eight Attractions,” “Seven Ancient Arrangements.” This taxonomic approach—treating complex cultural practices as collections of discrete, classifiable objects—transformed living traditions into Linnean taxonomies, reducing centuries of practice to reproducible formulas. By breaking down garden design into a catalog of elements that could be selected and arranged according to Western aesthetic preferences, Conder inadvertently created a framework for cultural appropriation that divorced Japanese garden elements from their original meanings and contexts. His illustrations further reinforced this taxonomic approach, presenting garden elements as decontextualized specimens to be collected and arranged, much like botanical specimens in a natural history museum. As Michel Foucault argues in The Order of Things, such taxonomic impulses are never neutral but encode historically specific epistemologies and power relations. Conder’s classifications reduced Japanese gardens to a lazy aesthetic, disconnected elements stripped of philosophical, spiritual, and historical nuance, easily appropriated or commodified within Western cultural frameworks.” 3.

Key also to taxonomic reduction of the Japanese garden to elements is that it allowed it to be sellable to a bourgeois audience for whom it was a symbol of status. In his Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin writes of the apartment.

The private individual, who in the office has to deal with reality, needs the domestic interior to sustain him in his illusions. This necessity is all the more pressing since he has no intention of allowing his commercial consideration to impinge on social ones. In the formation of his private environment, both are kept out. From this arises the phantasmagorias of the interior, which, for the private man, represents the universe. In the interior, he brings together the far away and the long ago. His room is a box in the theater of the world.4.

In shifting from rural working farms to suburban pleasure gardens, the domestic landscape embraced the same logic Benjamin identified within bourgeois interiors. Both interiors and gardens collected exotic elements transformed into “dream images”—visual fragments stripped of their original context yet invested with illusory meaning, composing the “phantasmagoria” of middle-class existence. By “phantasmagoria,” Benjamin refers to how the bourgeoisie surrounded themselves with objects that created an appearance of authenticity and connection to distant cultures, while actually reinforcing their separation from those cultures. Japanese garden features, detached from cultural and spiritual foundations, were marketed as symbols of authenticity and timelessness—allowing suburban homeowners to feel connected to ancient traditions while actually participating in their commodification. Paradoxically, the mass reproduction of these elements—the widespread commercialization of stone lanterns, wooden bridges, and exotic plants—eroded the very authenticity they claimed to preserve. For Benjamin, this reveals a core contradiction: collectors sought authenticity through precisely those mass-produced (or industrially propagated) items that inherently undermined genuine cultural meaning.

Chief among these —and easiest to incorporate into American gardens were Japanese plants, which catered to a nineteenth century fascination with exoticism . Already by the 1880s, nurseries on both coasts had begun importing and promoting Japanese plants. Parsons & Sons Nursery in Flushing, New York, and the Theodore Payne Nursery in California were among the earliest to offer specimens such as Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Japanese bamboo (Phyllostachys spp.), and Japanese flowering cherry (Prunus serrulata). These were often advertised as exotic novelties or hardy Eastern ornamentals, stripped of their cultural significance and sold to American gardeners eager for the unusual. The propagation process was meticulous and time-consuming—plants collected in the 1860s often weren’t commercially available until the 1880s. At Parsons Nursery, Swiss propagator J.R. Trumpy developed specialized grafting techniques for challenging species like Japanese maples, reportedly grafting “10,000 plants with his own hand” in a single year. Nurseries capitalized on the exotic appeal and novelty factor of these plants—Kissena Nurseries advertised in 1876 that “Their Japanese Department now includes more than 150 varieties… Many of these varieties are unknown in Europe,” highlighting their exclusivity and positioning them as must-have curiosities for status-conscious garden collectors.5.

Contemporary academic discourse interprets Western fascination with Japanese aesthetics through the lens of Edward Said’s Orientalism, emphasizing Western exoticization and romanticization of Eastern cultures. But by focusing exclusively on Western texts and perceptions, this framing reinforces the power dynamics it critiques. Japanese officials, artists, and intellectuals in Meiji-era Japan (1868–1912) were neither passive nor simply appropriated; they intentionally selected and exported cultural elements to shape international perceptions. Figures such as curator Okakura Kakuzō, author of The Book of Tea (1906), strategically promoted an image of Japan designed to resonate with Western audiences as part of Japan’s broader geopolitical ambitions. By positioning itself as the authentic repository of Asian culture, Japan sought cultural and political advantage over China, then viewed by Western observers as diminished. Historian Kendall Brown points out that these major American fairs also coincided with key moments in Japan’s imperial expansion. The Chicago Columbian Fair of 1893 took place on the cusp of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, while the San Francisco Mid-Winter Exposition occurred during that conflict itself. The subsequent St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition marked the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. These weren’t merely coincidental timings—they reflected a sophisticated strategy of cultural diplomacy on Japan’s part. While front-page headlines described a rapidly militarizing Japan engaged in territorial expansion, visitors to the fairs encountered an entirely different vision: a Japan of tranquility, artistic refinement, and natural harmony. This dual presentation allowed Japan to assert its status as a modern power while simultaneously cultivating a non-threatening image through its gardens and cultural displays. In the exhibition halls, Japan showcased its industrial and technological advances, demonstrating it could compete with Western nations. In its gardens and pavilions, however, it presented itself as the refined repository of Asian aesthetics and spirituality—a feminine counterpoint to its masculine, modernizing public image. 6. While Said’s critique importantly highlights Western projections onto Eastern cultures, the Japanese case underscores a crucial distinction: cultural appropriation wasn’t solely imposed externally but was also actively shaped by Japan’s deliberate self-presentation. This recognition doesn’t negate the ecological or philosophical issues resulting from superficial Western appropriations; rather, it emphasizes the complexity of these historical interactions as intentional, reciprocal processes.

It was against this backdrop—of aesthetic fascination, cultural projection, and botanical commerce—that Japanese cherry trees entered the American landscape not just as ornament but as diplomatic symbol. Central to this shift was Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, a travel writer whose interest in Japanese culture began at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Captivated by the Japanese pavilion and garden she immediately began writing articles, reporting from the exposition. She soon became a travel writer and traveling to Japan in the 1880s, became a major advocate for the country and its aesthetics. After returning in 1885, Scidmore proposed planting cherry trees along the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. Her advocacy met bureaucratic indifference until 1909, when she gained the support of First Lady Helen Herron Taft, who had lived in Japan and shared Scidmore’s enthusiasm. Their timing coincided with Japan’s own efforts to promote goodwill abroad. Consequently, the city of Tokyo, supported by chemist Jokichi Takamine and other officials, gifted thousands of cherry trees to the United States.

The first shipment in 1910, infested with insects, was destroyed. But a second, healthier consignment of over 3,000 trees arrived in 1912. On March 27, 1912, Taft and Viscountess Chinda, the Japanese ambassador’s wife, planted the first two Yoshino cherries along the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C. The ceremonial act was framed as a gesture of friendship, not politics. The symbolism, however, ran deep. Japan selected twelve varieties of cherry tree to showcase its geographic and botanical diversity; in return, the United States sent flowering dogwoods to Japan. 7.

The planting of cherry trees at Branch Brook Park, initiated by Caroline Bamberger Fuld in memory of her sister, likewise emerged within this cultural milieu shaped by Japonisme and botanical diplomacy. While the planting in Newark lacked the explicit diplomatic orchestration of the National Mall’s event, it nonetheless reflected similar desires—to bring Japan’s iconic seasonal experience into the American landscape and imagination. Like Scidmore, Bamberger Fuld had been captivated by seeing the trees in Tokyo and became determined to not only bring them to Branch Brook Park, a park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted’s sons in the firm’s characteristic fashion of a series of lawns and wooded areas. She was also determined to plant more than at the National Mall and imported so many that the park had to be extended. 8. Today, a vast array of individuals from a Pakistani bride in a niqab wedding dress to Japanese teens dressed in Lolita fashion gather under the trees, echoing Japan’s centuries-old tradition of hanami.

Without denying the cultural importance of either the National Mall or Branch Brook Park to Americans, Japanese Americans, and the Japanese, we need to reflect more deeply on the consequences of such exchanges. The aesthetic appeal of these plants has often blinded us to the colonialist impulses behind such trade as well as the ecological consequences. In my earlier essay, “A Trip to Lithuania and the Baltics,” I explored how invasive species travel along networks established through global trade and colonial exploration. Carl Peter Thunberg, a Swedish naturalist and student of Linnaeus, accessed Japan under the pretense of being Dutch as a physician for the Dutch East India Company. Although the Japanese authorities strictly confined Dutch traders to Dejima, an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay, Thunberg’s medical skills in treating syphilis—known locally as the “Dutch disease”—earned him limited freedoms. This allowed him brief excursions into Nagasaki and participation in a diplomatic journey to Edo (present-day Tokyo). Thunberg documented numerous plants previously unknown in Europe, notably Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), winged euonymus (Euonymus alatus), and Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii). Many of these species later became ecologically disruptive in North America. Half a century later, Philipp Franz von Siebold, another physician-botanist connected with Dutch trading interests, expanded significantly on Thunberg’s groundwork. Unlike Thunberg, Siebold managed extensive plant nurseries both in Japan and subsequently at Leiden, actively introducing living plants into European horticulture. Among his most consequential introductions were Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), now notorious for aggressively reshaping Western landscapes, and Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), widely planted ornamentally but invasive throughout the southeastern United States. Siebold’s botanical collections and nursery distributions solidified European fascination with Asian flora, embedding it firmly in Western garden aesthetics and, unintentionally, contributing to severe ecological disruption abroad. Although the introduction to Japanese gardens in the late nineteenth century led to the first burst of interest in Japanese plants, their spread into in middle-class gardens was, like the rise of Hibachi restaurants, a product of return of GIs from the Pacific Theater and Occupied Japan.

Many plants initially imported for ornamental purposes have escaped cultivation in the United States, significantly disrupting local ecosystems, reducing biodiversity, and altering habitats. Invasive species from every continent can now be found in the United States, but Japan poses a particular problem because its climate closely mirrors that of the northeastern United States, enabling Japanese plants to thrive aggressively and the historical enthusiasm for Japanese horticulture that I have described in this essay has resulted in widespread introductions lacking natural controls. From Japan, invasive plants include Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), Winged Euonymus or Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus), porcelain berry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus).9. Nor is this a one-way transaction. North American species, such as Tall Goldenrod (Solidago altissima, also known as Late or Canada Goldenrod), White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima), Lance-leaved Tickseed (Coreopsis lanceolata), and Cutleaf Coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata), all introduced to Japan as ornamental plants, are considered invasive and have aggressively spread and displaced native vegetation. Raccoons (Procyon lotor), popularized as pets after the 1977 anime Rascal the Raccoon, also became widespread invasive pests in Japan, significantly contributing to the decline of local wildlife.

The ecological impact of Japanese ornamental plants in North America extends beyond simple displacement of native species, creating complex cascading effects throughout ecosystems. Japanese barberry offers a particularly alarming case study in interconnected harm. Research demonstrates that barberry infestations significantly reduce “numbers and diversity of arthropod communities in forests” where it spreads, particularly affecting generalist predators like ants and spiders. This disruption ripples upward through the food web to impact birds and larger predators. Even more concerning, multiple studies have established a direct relationship between Japanese barberry and ticks carrying Lyme disease. Similarly, the popular Kousa dogwood’s seemingly benign presence masks a more insidious threat—researchers have determined that the anthracnose fungus devastating native flowering dogwoods was likely imported on Kousa dogwoods, which had co-evolved with it and thus had a degree of resistance. This pattern of imported plant, imported disease, and devastated native species extends to many ornamental introductions, creating far-reaching ecological consequences that reverberate through entire ecosystems.10.

Ironically, Kousa dogwoods brought anthracnose blight to North America, devastating native flowering dogwoods, yet are cynically marketed today as disease-resistant alternatives. For example, the Arbor Day Foundation promotes Kousa dogwood for being “more resistant to diseases and insects than flowering dogwood,” emphasizing its hardiness without acknowledging the ecological trade-offs. This marketing persists despite scientific evidence showing that Kousa dogwood is now officially classified as an invasive species in some regions, with researchers noting there is “commonly a lag between when a plant species is introduced into a new home and when it begins to behave invasively,” a pattern now clearly emerging with Kousa dogwood.11. In my own garden, mature specimens planted by previous owners evoke conflicting feelings: their beauty delights me, yet their invasive potential troubles me deeply. For now, I manage this tension by removing any seedlings to minimize ecological impact.

Meanwhile, trade in exotic ornamental plants continues, its environmental and ethical costs wildly out of line with the value it produces. Estimates suggest that the trade is valued at over $50 billion globally and is growing rapidly, driven by consumer demand and fueled by consolidated corporate supply chains. The majority of profits accrue not to independent growers but to multinational breeders, biotech firms, and factory-scale growers who supply big-box retailers and online platforms. Companies like Costa Farms in the U.S., Dümmen Orange in the Netherlands, and Syngenta Flowers in Switzerland dominate production, propagation, and global distribution. Royalties on patented cultivars, economies of scale, and vertical integration ensure that profits concentrate at the top. Meanwhile, in the United States, scientists have concluded that the primary pathway for invasive plants is the horticultural trade: 40% of invasive plants were originally introduced for horticultural purposes. Globally, the UN estimates that invasive species now cause over $423 billion in damage annually, a figure that does not account for intangible ecological loss.12.

The planting of Japanese species in the United States is almost inevitably done as Linnaean “specimens”—without any further regard for where their ecology, the Japanese garden aesthetic, or the philosophy behind it. Add some concrete lanterns or other “Japanese” garden furniture, and the effect is supposedly complete. While cultural mixing is integral to human society—appointing guardians to police against “cultural appropriation” is an open door to xenophobia and racism—the American reduction of Japanese garden aesthetics to marketable tropes exemplifies cultural appropriation divorced from deeper understanding. This reduction commits symbolic violence against the Japanese garden tradition, deeply rooted in Shinto, Buddhist practice, and Japan’s unique natural conditions. At its core is the principle of harmony—gardens are intended not to dominate or impose order upon the landscape, but rather to reveal, clarify, and intensify the inherent beauty and subtle rhythms of nature. A garden in this tradition is less an artistic creation imposed upon the earth than a mindful collaboration with it, shaped through careful observation and responsive design. Indeed, the true appeal of Japanese gardens—even for Western observers—is found not simply in exotic appearances but in their sensitive integration with and reflection of their natural environment. This is the essential quality worth emulating—not through literal reproduction but by adapting the underlying principles. Beyond aesthetics and imported specimens, authentic Japanese gardens fundamentally respond to the unique conditions of a specific site. The 11th-century gardening manual Sakuteiki emphasizes this principle, advising gardeners to “follow the request of the stone” and to carefully consider the natural tendencies of water, plants, and earth. Japanese gardening emphasizes indigenous plants appropriate to local conditions. Unlike the Western tradition, which imposes geometric order irrespective of existing conditions, the Japanese approach collaborates sensitively with the landscape. This counters Western preferences for symmetrical, perfected forms by highlighting simplicity and irregularity. Gardens become places to reflect upon life’s transient nature. Western culture frequently reduces Japanese aesthetics to kitsch—miniature Zen gardens with sand rakes on executive desks exemplify such superficial appropriation.

Yet my visit to Japan did not leave me disillusioned. On the contrary, Saihō-ji inspired me to think about the possibility of a new garden aesthetic paralleling the Japanese tradition, but firmly rooted in the local ecology and cultural history of the American Northeast. This is the task ahead: not merely imitating the Japanese aesthetic, but cultivating our own, grounded deeply in our regional ecology and cultural identity. Just as Japanese gardens evolved through centuries of attentive observation of landscapes and seasonal rhythms, our Northeast native garden philosophy must emerge from similar attentiveness to our own ecological context.

Why plant Japanese cherry trees (Prunus serrulata) when we have native Eastern redbuds (Cercis canadensis) that are equally beautiful, with their myriad tiny blooms attached directly to branches, the delicate petals they scatter across the ground, and their heart-shaped leaves unfurling afterward? Why not reflect on the impermanence of life through the spring ephemerals of the Northeast—the delicate flowers of sharp-lobed hepatica (Hepatica acutiloba), Virginia spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), or rue anemone (Thalictrum thalictroides)? What of the white bracts of the flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), as beautiful as those of the Kousa (Cornus kousa)? Why not ponder the three-part symmetry of white trillium (Trillium grandiflorum), the emerging shoots of Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum biflorum), or the choreographed unfolding of the Northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum)? Our native landscapes offer their own meditations on impermanence, resilience, and renewal—qualities that Japanese garden aesthetics have long celebrated in their own flora.

The new Northeastern garden will embrace a distinct seasonal rhythm: not the carefully staged progression of bloom that characterizes many Western gardens, nor the restrained minimalism of karesansui, but rather the dramatic transformations unique to our climate—the stark sculptural forms of winter giving way to the ephemeral urgency of spring, followed by the layered complexity of the summer woodland and the fiery crescendo of autumn.T his approach requires not just substituting native plants for exotic ones, but developing a fundamentally different relationship with time, change, and place—one that honors both our ecological inheritance and the contemplative possibilities that Japanese garden philosophy has long recognized. By rejecting both the colonial impulse to collect exotic specimens and the suburban compulsion toward ornamental control, we might create gardens that truly belong where they grow—gardens that deepen our connection to the living landscapes of the Northeast rather than imposing fantasies borrowed from elsewhere. This is the task that lies ahead: not to imitate another culture’s aesthetic achievements, but to cultivate our own garden tradition, rooted in the specific ecology, history, and seasonal rhythms of this place

1. Karl Bareis, “Beginnings of Japanese Influence on American Design—The International Expo of 1876,” Kezurou‑kai USA, February 28, 2023, https://kezuroukai.us/beginnings-of-japanese-influence-on-american-design-the-international-expo-of-1876/. The quote from the Atlantic is from “Characteristics of the International Fair,” The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 38, no. 225 (July 1876), 85–91, https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/archives/1876/07/38-225/132121881.pdf. The most comprehensive source on the arrival of the Japanese garden in the United States is Christian Tagsold, Spaces in Translation: Japanese Gardens and the West (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). The quoted description is from Thompson Westcott, Centennial Portfolio (Philadelphia: T. Hunter, 1876), 50. ↩

2. For more, see Tagsold. ↩

3. Josiah Conder, Landscape Gardening in Japan (Tokyo: Kelly and Walsh, 1893); Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences (London: Routledge, 1994). ↩

4. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 9. ↩

5. Peter Del Tredici, “The Introduction of Japanese Plants Into North America,” *The Botanical Review* 83(2) (2017): 109-132. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317835179_The_Introduction_of_Japanese_Plants_Into_North_America ↩

6. Kendall H. Brown, “Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940,” SiteLINES: A Journal of Place, vol. 4, no. 1 (Fall 2008), 13–16, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24889323. See also Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978). ↩

7. Diana P. Parsell, Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023). ↩

8. Mark Di Ionno, “The Story behind Branch Brook Park’s Cherry Blossom Trees,” NJ.com, March 2016, https://www.nj.com/news/2016/03/the_story_behind_branch_brook_parks_cherry_blossom.html. ↩

9. National Invasive Species Information Center, “Terrestrial Plants,” https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/plants; A. J. Downing, ed., The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, vol. 25 (1870): 161, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Horticulturist_and_Journal_of_Rural/QRPWxM8UOGEC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA161; Peter Del Tredici, “Untangling the Twisted Tale of Oriental Bittersweet,” Arnoldia 71, no. 3, https://arboretum.harvard.edu/stories/untangling-the-twisted-tale-of-oriental-bittersweet/; National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan, “List of Regulated Living Organisms under the In vasive Alien Species Act: Plant Kingdom,” https://www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/etoc8_plants.html. ↩

10. Ed Ricciuti, “Impact of Invasive Japanese Barberry Cascades Through Local Food Webs,” Entomology Today, September 13, 2019, https://entomologytoday.org/2019/09/13/impact-invasive-japanese-barberry-cascades-through-local-food-webs-arthropods-insects/. Kristen Cole, “Lyme Disease-Toting Ticks Abundant on Common Invasive Plant, New Study Finds,” Trinity College News, April 18, 2023, https://www.trincoll.edu/news/lyme-disease-toting-ticks-abundant-on-common-invasive-plant-new-study-finds/.Trinity College Kim Krieger, “Controlling Japanese Barberry Helps Stop Spread of Tick-Borne Diseases,” UConn Today, February 27, 2012, https://today.uconn.edu/2012/02/controlling-japanese-barberry-helps-stop-spread-of-tick-borne-diseases/. and Thomas Christopher, “The imported kousa dogwood was once hailed as substitute for dying native dogwood trees. Now it’s classified as an invasive species,” The Berkshire Eagle, September 14, 2023, https://www.berkshireeagle.com/arts_and_culture/home-garden/thomas-christopher-be-a-better-gardener-kousa-dogwood-invasive-species/article_561980b2-4da7-11ee-8ec5-db1eabf34a6e.html↩

11. ”The Kousa Dogwood,” Arbor Day Foundation, March 12, 2019, https://www.arborday.org/perspectives/kousa-dogwood. ↩

12. Evelyn M. Beaury, Miranda Patrick, and Bethany A. Bradley, “Invaders for Sale: The Ongoing Spread of Invasive Species by the Plant Trade Industry,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 19, no. 10 (2021): 550–556, https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/fee.2392. ↩