I have a new blog post up on varnelis.net. The text and some imagery is here, but the original post has many more images in the slide galleries so I encourage you to go there for more.

In 1770, Pierre Lecouille was born in the small Burgudnian village of Montagny-les-Beaune. He was destined to become one of France’s most visionary architects and draftsmen although he has been little known until recently. Inspired by Phillippe Duboy’s book on Jean-Jacques Lequeu, I have become interested in this period and, in turn, the work of Lecouille, a close contemporary of Lequeu.

The son of a winemaker, Pierre’s artistic talents were evident from an early age. He would spend hours sketching the rolling vineyards and charming villages that surrounded his childhood home, capturing the interplay of light and shadow on the landscape with an uncanny precision. Pierre’s natural talent caught the eye of a visiting Parisian architect, Henri de Gévaudan, who was struck by the young boy’s ability to convey not just the physical reality of the landscape, but also the underlying emotional tenor of the scenes he depicted. Recognizing the potential in the young artist, Gévaudan took him under his wing and brought him to Paris.

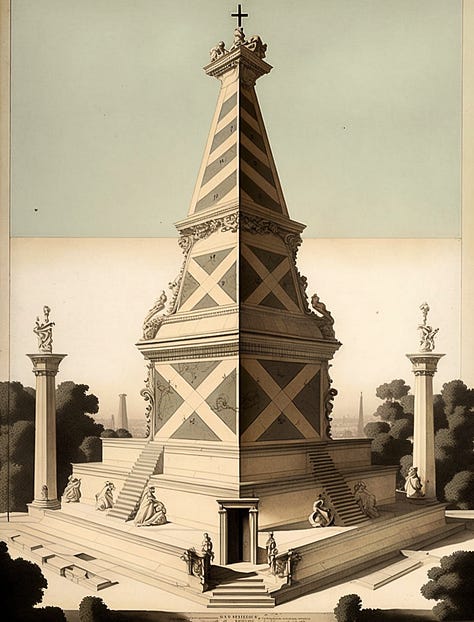

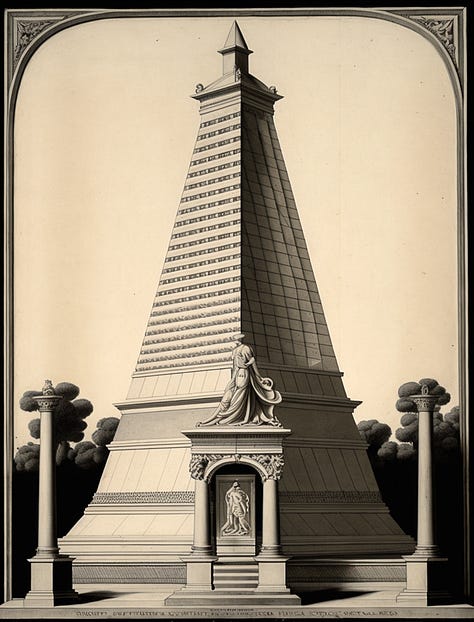

In Paris, Pierre was exposed to the works of visionary architects Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.. Profoundly moved by their daring designs, which sought to encapsulate the ideals of the Enlightenment in built form, Pierre was inspired to take his own work in a similar direction. As a young designer, his diaries reveal a mind preoccupied with death and he turned out fantastically inventive funerary monuments, which he even turned into a lucrative occupation for a brief period of time. Although most of the cenotaphs he designed were of the sort of scale a minor courtier or gentleman might build for himself, others were of vast size, resembling Egyptian pyramids and intended to honor kings and powerful advisors.

As France was swept up in the turmoil of the French Revolution, Lecouille proved his ideological flexibility, turning on a dime to design vast prisons to house the enemies of the revolution and, more menacingly, developing his Éclabousser, or splattering machine, an alternative to the guillotine that proved quite unpopular because it was far more like the barbaric breaking wheel that the guillotine was supposed to replace, even if it did have the advantage of turning the deceased into pulp (which he called “veau” or veal) that would then be mixed with gypsum to encourage the growth of grapevines (this did not work).

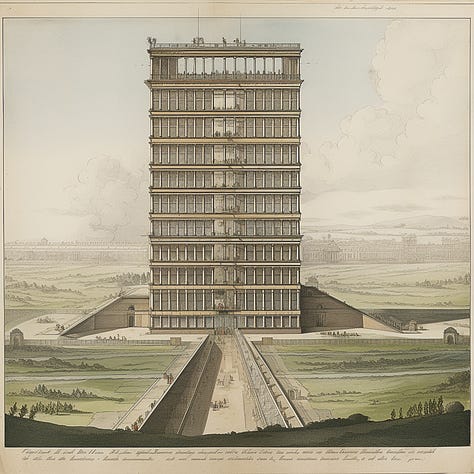

Lecouille survived the Revolution and found himself drawn to the radical ideas of social reformers. In the 1810s, he was among the first to embrace the theories of Charles Fourier. Fourier’s concept of the phalanstery—a utopian community designed to foster cooperation and mutual support among its inhabitants—resonated deeply with his own architectural and social vision. Lecouille devoted himself to the creation of a series of visionary architectural designs for his own interpretation of Fourier’s phalansteries. His drawings, executed in delicate washes of sepia ink and watercolor, depicted vast, monumental structures that seemed to emerge from the landscape itself.

Lecouille’s innovative designs drew upon the architectural principles of the ancient world, but they were also infused with a distinctly modern sensibility. He believed that architecture should not only be beautiful but should also serve the needs of society and contribute to the happiness and well-being of its inhabitants. In his utopian communities, Lecouille imagined a world in which the divisions of social class and wealth were erased, and people lived together in harmony and mutual support.

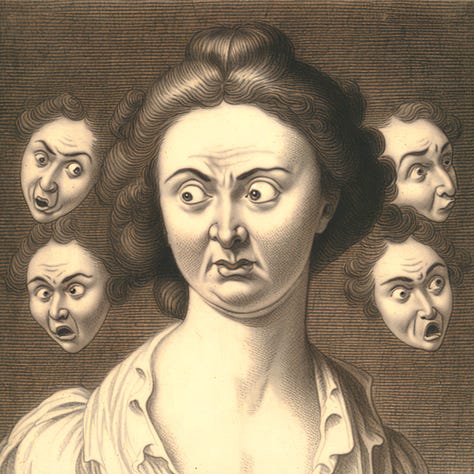

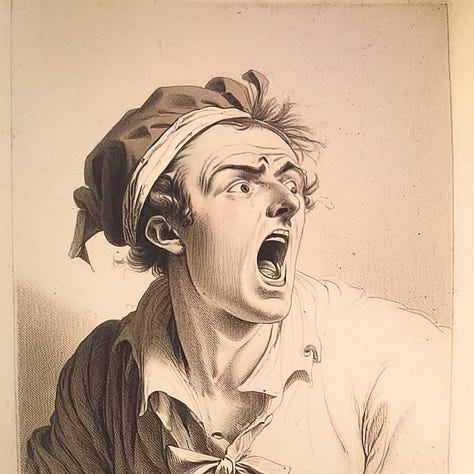

Like Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Lecouille not only worked in architecture, he also conducted physiognomic studies, drawing a series of disturbing faces which were long thought to be inmates from an asylum but are now understood to be images of other architects, their wives, and even self-portraits.

Though Pierre Lecouille’s visionary designs were never realized during his lifetime, his work has left a lasting impact on the world of architecture and urban planning. His drawings and writings, which were published posthumously in a folio entitled “Les Rêves d’un Architecte” (The Dreams of an Architect), continue to inspire architects and urban planners to this day.

Pierre le Couille passed away on October 9th, 1845, leaving behind a legacy of incredible, visionary designs that have since become emblematic of the utopian aspirations of the Enlightenment. His work remains a testament to the power of architecture to not only reflect but also shape the society it serves, and to the enduring dream of a more harmonious, egalitarian world.

This is the first of three drafts of Critical AI Art Projects that I am going to send out this week. I have been working too long on getting more thorough descriptions of these out the door, and, after talking with my good friend Lev Manovich, I realize that perfection is our enemy here. By the time the text is improved, the image generation technology will be too (although not always: most of these were made with Midjourney 4, version 5 being a bit of a step back) and a vicious spiral starts. This text and these images aren’t exactly where I’d like them to be, but it’s a start. I’ve revised the other projects substantially since I published them and sitting on these won’t get them moving forward.

Like all of my Critical AI Art projects, Pierre Lecouille doesn’t exist, except as the output of an AI image generator. But in Lequeu: An Architectural Enigma, Philippe Duboy suggests that Marcel Duchamp fabricated Jean-Jacques Lequeu’s drawings while he worked at the Bibliothèque nationale de France from 1913 to 1914 (Lequeu’s name turns out to be a dig at Duchamp’s arch-nemesis, Le Corbusier, LeQ (“the dick”) to LeC, but also sounds remarkably like L.H.O.O.Q). I had the privilege to see the drawings attributed to Lequeu at the Morgan Library in 2020, right before COVID closed down the city. It was a delight, but it also made me receptive to Duboy’s (otherwise controversial and often-dismissed) thesis.

Lequeu/Duchamp demonstrate the construction at the heart of histories, including histories of art and architecture. Historians are storytellers, weaving histories that can be as much fiction as fact. Who really knows if Lequeu’s work was a great deception by Duchamp, or if Duboy’s work was the deception? Historians—and readers of history—create their own meanings and interpretations of history. Thinking of Roland Barthes S/Z for a moment, we might recall his juxtaposition of “readerly” texts that don’t challenge the reader to participate in the creation of a text’s meaning with “writerly” texts that invite readers to actively construct meaning.Lecouille suggests that the history of architecture can be writerly, a way of parrying an architecture history that has grown old and is unable to accept new interpretations (except as dictated by academic politics) as well as counteracting the popular and simplistic use of AI in the architectural academy that envisions creating furry or feathery blobs. Let’s investigate AI image generators for what they are, a glimpse into our collective unconscious.