Under oversaturation, as I analyze in this historical reflection, we reduce sites to shareable images, replacing personal engagement and memory with replicable moments, eroding interaction and attention.

It’s winter, so I have been writing more about my art practice and my reflections on history and theory. In the spring, there ought to be more essays on landscape as well, but my first career is in art and architecture, so onwards. You can find the essay on my site as well.

In 2013, I proposed a Network Architecture Lab symposium at Columbia centered on the topic of oversaturation—a concept that I envisioned encompassing not just what would become known as “overtourism,” but the crisis of cultural overproduction as a whole. Even though we had identified a funding source for the symposium, mysterious administrative forces kept throwing wrenches in the works. Perhaps it conflicted with the school’s larger agenda; after all, how could an institution premised on constant growth, endless publication, and global expansion confront the consequences of those conditions? Perhaps there was concern that donors might be turned off? It was still the heady era of post-GFC growth, when urban boosters hoped that a shiny new museum or concert hall would bring in tourists by the plane full. We tossed in the towel and moved on to other projects instead, things architects could more easily understand, things that weren’t going to get frowned on by the administration. Coined on travel industry website Skift some three years later, “overtourism” rapidly became a buzzword. But oversaturation was a broader concept, and as I am outside university supervision these days, it’s time to revisit and explore it in further depth.

As I started this essay a few months ago, I was in France on a variety of matters—visiting two shows on my father’s paintings (one at the Centre Pompidou and one at the Fondation Vasarely) as part of the Saison de la Lituanie en France, attending a residency in the Pyrénées, and exploring parts of the country that I had not previously visited. Besides France, I went abroad several times during the past year—to Japan, Berlin, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Overtourism dogged these travels, especially on the April trip we made to Tokyo and Kyoto. We had a miserable morning at the Sensō-Ji Temple in Asakusa, Tokyo, which tourists had overrun. Burned by this experience, we decided to skip such sites. In Kyoto, we passed on notable locations like the Fushimi Inari Shrine, Gion, and the Imperial Palace. This was disappointing, but we had our hands full going to locations off the beaten path. We didn’t take selfies—what, precisely, is the point of those?—but we were still tourists, no different than the folks wearing Disneyworld T-shirts, although we made efforts to be respectful of local life. For his part, our son—who is now pursuing a degree in game studies—took late-night trains out to distant suburbs to find obscure video games at used game stores, just like my father endlessly visited bookstores for art books and I looked for books on architecture. Obsessions with culture cross generations in a family of artists, even as the objects of that obsession may change.

Tourism is a foreign country for me. With my father as an artist in a single-income household, we weren’t wealthy; his time and money went into his book, map, and art collections. I have a dim memory of a couple of brief vacations at the beach—ordered by his doctor—while I was very young, but apart from one night at Niagara Falls in 1976, we did not spend a single night away except for his professional interests, and even those vanished after we left Chicago in 1979. When we went somewhere, it was a research project: museums were inspiration for an artist, not some kind of amusement. He was not a foodie. Eating was for sustenance only, the cheaper the better. Amusement parks and theater were nothing but wastes of money. Disneyworld was never in the cards; I didn’t even ask about it.

By the time I had graduated college and had the opportunity to travel, I was already an historian of architecture. My first trip abroad was a month in Italy on a Grand Tour that I’d received a scholarship for as part of my studies. The allowance for room and board were minimal, but it gave me the opportunity to see buildings firsthand. For an historian, travel to see buildings was a prerequisite. In retrospect, I wonder if I chose the profession to permit myself to travel or at least rationalize the activity to myself and my father. Still, it meant that my own travels always had a research component to them.

There is nothing new about all this. The practice of tourism itself can be traced back to the Grand Tour, a tradition that began in the 17th century as an educational journey for young European aristocrats, primarily from Britain. Designed to cultivate the intellect and refine the sensibilities of young aristocrats by exposing them to the art, culture, and architecture of classical Europe, the Grand Tour was more than mere travel—it was an immersive experience to shape the mind and character. The traveler often spent months or even years abroad, moving through the great cities from Paris to Florence to Rome, while a tutor (the cicerone) gave firsthand instruction on the sights and their relationship to the classics. Studying ruins firsthand, travelers would contemplate the fall of that empire even as Britain was building its own.

Tourism and imagery were tied together through their origins in the rise of print culture, which made classical literature and art widely accessible. Early print was dominated by the reproduction of Greek and Roman classics, sparking widespread curiosity about the landscapes and monuments of ancient Rome, Greece being occupied by the Ottoman Turks and inaccessible to the West, a condition compounded by the achievements of Renaissance Italy. The eighteenth century saw the emergence of travel literature and illustrated guides that created idealized representations of these landscapes, fundamentally changing how tourists experienced and interacted with places. This era was also marked by the rise of the “picturesque,” a concept first introduced by writer William Gilpin in his 1768 “Essay Upon Prints,” a short treatise on how to collect the emerging media. Gilpin’s “picturesque” was an effort to appreciate landscapes by treating them as mediated images through careful framing. This approach was augmented by devices like the Claude Glass, a small, portable, dark-tinted convex mirror named after the painter Claude Lorrain, whose idealized pastoral scenes set the standard for “proper” composition, this small, portable, dark-tinted convex mirror reflected back a softened, flattened, and slightly idealized image, making any view appear more like a painting. Using the device required an almost ritualistic set of actions: the viewer would face away from the scene, hold up the mirror, and adjust the position until the reflection achieved the desired effect. This peculiar choreography—turning away from reality to see it better—perfectly encapsulates how the Grand Tour taught travelers to experience place through representation. The Claude Glass transformed raw nature into composed views, making landscape itself into something that could be collected and consumed. Even more significantly, it trained viewers to expect mediated images and even prefer them to direct experience, establishing a pattern that would shape tourism for centuries to come.

But actual image-making was menial work, not something the British upper class could afford to be seen indulging in, moreover, it required extensive time for training that was better spent with the humanities, law, and other studies. Instead, the wealthier Grand Tourists acquired art and antiquities systematically, building personal collections while also transferring cultural capital from Italy to Britain, thus forming the basis of major British institutions like the British Museum.

To satisfy the growing interest in architectural imagery, artists such as Canaletto and Giovanni Battista Piranesi produced images of local sites for these audiences. Canaletto dominated the market for vedute (view paintings) in Venice, creating meticulously detailed scenes that satisfied tourists’ desire for perfect memories of their Italian sojourn. Canaletto’s vedute were prized for their apparent objectivity and precision—though he frequently adjusted perspectives and rearranged architectural elements to create more pleasing compositions. His capricci, blending real and imagined elements into fantastical compositions, appealed to collectors drawn to a more romanticized vision of the past, offering both documentation and escapism. His primary patron, Joseph Smith, the British Consul in Venice, effectively operated as his agent, selling Canaletto’s works to British travelers and eventually selling his own massive collection to King George III. This relationship proved so profitable that when British tourism to Venice declined during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-48), Canaletto followed his market to England, painting similar views of London for aristocratic patrons.

Many tourists saw Canaletto and Piranesi’s vedute before they ever visited Venice and Rome, creating a certain level of expectation. Some enthusiastically proclaimed that the real thing exceeded its image, but others were disappointed by the reality and the latter experience only increased as the eighteenth century wore on and living conditions in London improved.

The market for views was hierarchical. Canaletto’s oil paintings commanded the highest prices and greatest prestige, purchased by wealthy aristocrats as the ultimate proof of cultural refinement. Below these were watercolors and gouaches by artists like Francesco Guardi, who offered a quicker, more atmospheric, and more affordable alternative. At the bottom were etchings and engravings by artists like Piranesi and Giuseppe Vasi, mass-produced for less well-heeled tourists (Canaletto’s works were also reproduced for wider consumption as prints by Antonio Visentini and other engravers). Working in etching, a “lower” medium and initially catering to less sophisticated tastes, Piranesi transformed architectural representation through works such as his Vedute di Roma. These dramatic views of Rome’s ruins combined archaeological precision with theatrical imagination, creating images that were simultaneously documentary and fantastical. Where Canaletto presented a vision of Venice—then in decline—as a great and proseperous city, Piranesi’s Rome was a city of ruins, inhabited by as many cows and goats as people. Both artists heavily embellished their work. Canelleto’s Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons) series went further, using architectural elements from Roman ruins to create impossible, sublime spaces that would influence everything from Romantic poetry to surrealist art.

Piranesi transformed what was essentially a form of commercial art into something more profound: a way of experiencing architecture through imagery that was both documentation and affect, establishing patterns of visual consumption that would shape centuries of architectural representation. Today, Piranesi is now highly collectable: his Vedute di Roma was my father’s most prized possession and, although our family donated it to the Lithuanian National Museum, would be worth a small fortune today.

Photography’s role in tourism began soon after the medium’s invention, with figures like Maxime Du Camp and Francis Frith leading the way. Using photography to document their journeys, these early travelers created lasting visual records of the places they visited. Du Camp, who traveled to Egypt and the Middle East in the 1840s, captured images of ancient monuments and ruins, which were later published alongside his travel writings in Égypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie (1852). Believing that there was a large market for imagery outside of the traditional Grand Tour sites, Frith made several trips to Egypt and Palestine in the 1850s and 1860s. His photographs of ancient ruins and landscapes became highly sought-after souvenirs and were widely published in albums such as Egypt and Palestine Photographed and Described (1858-1860) and reproduced on postcards. Frith’s detailed and carefully composed images shaped how Europeans perceived these distant lands, blending tourism with a kind of visual ethnography.

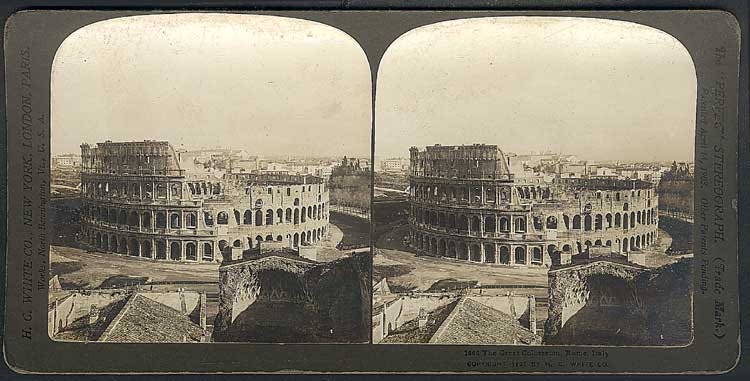

Nor was photography limited to merely emulating painting. New technologies created unprecedented opportunities for visual culture. In particular, the stereoscope allowed viewers to see distant sights in three dimensions. This required precise calculation: two photographs had to be taken simultaneously from points about two and a half inches apart (matching the distance between human eyes) using a special double camera and then precisely printed and mounted on cardstock. When viewed through the stereoscope’s lenses, the images merged in the viewer’s perception to create an uncanny sense of depth and presence. Exhibited at the 1851 exhibition at the Crystal Palace, the stereoscope captivated Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and the attendant publicity led to some 250,000 being rapidly manufactured and sold. The London Stereoscopic Company, founded in 1854, operating under the slogan “No home without a stereoscope,” sponsored photographers to travel the world and sold hundreds of thousands of stereoscopic cards. Underwood & Underwood, founded in 1881 in Ottawa, Kansas, became the largest American producer, publishing 25,000 cards per day by 1901 (I own a small collection of these that we found in the house my parents bought in Massachusetts in 1977). These companies employed photographers who followed established tourist routes across Europe and the Mediterranean, carefully positioning their double cameras to capture the same monuments and views that had attracted Grand Tourists. Specialized techniques enhanced the stereoscopic effect—positioning foreground elements to emphasize depth, using strong diagonals, and carefully calculating viewing angles to maximize the sense of space. Virtual tourism was possible for the first time, allowing distant spaces to be experienced in the parlor.

Another new photographic technology was the “magic lantern,” or lantern slide projector. Generally attributed to Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch scientist who also discovered the rings of Saturn, this technology was first developed sometime in the 1650s. Refined and popularized throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the magic lantern sent the light through a series of lenses to project images from glass slides onto a wall or screen. Initially, the device was largely used to produce spectacular displays of ghostly images such as skeletons, demons, and other supernatural figures to entertain and frighten audiences. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, educators and scientists began to recognize the magic lantern’s potential for illustrating lectures, using it to project scientific diagrams, landscapes, and other instructive images for audiences, a practice that became more widespread with the advent of photography and mass-reproduced glass slides. Institutions such as the Royal Institution of Great Britain and universities across Europe incorporated slide lectures into their regular programming. They were particularly important in fields that required visual examples, such as art history, architecture, and natural sciences. Art historian Heinrich Wölfflin pioneered formalist art history by putting two magic lanterns side by side. In doing so, he could compare and contrast different works of art in real-time, a method that became central to his comparative art historical approach and to art and architecture history courses until the era of PowerPoint.

As photography advanced, glass slides featuring photographs of paintings, buildings, and monuments were produced in increasing numbers, with firms like the Alinari Brothers playing a major role in documenting European art and architecture. Founded in 1854, Fratelli Alinari (the Brothers Alinari) specialized in documenting Italian art and architecture, producing thousands of photographs that became valuable resources for scholars and travelers alike. The Alinari Brothers’ photographs became staples in architectural study, particularly for scholars who could not easily visit the sites themselves.

These early travel photographers laid the foundation for a visual culture of tourism as well as for the forensic use of photography in the history of architecture. Architectural historians relied heavily on such visual documentation to inform their studies and deliver lectures. Soon, universities and museums developed slide libraries. Institutions like Columbia University, the Courtauld Institute in London, not to mention my own Cornell University amassed vast collections of slides, including images by photographers such as Frith and the Alinari Brothers together with images taken by their own faculty on research trips. These collections enabled architectural historians to compare buildings from different time periods and geographic locations, contributing to the development of the comparative method in architectural study.

Historians of architecture took up photography themselves, using it as a direct tool for research. Banister Fletcher used photography extensively to illustrate his arguments in his A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, employing Wöllfflin’s comparative method to create visual arguments that textual descriptions alone could not achieve. Many historians like Nikolaus Pevsner and John Summerson were also known to document their travels through photography, capturing the buildings they studied in meticulous detail. Their images, often included in their writings, provided not only records of their subjects but also a means of interpreting the architectural qualities of the structures. Pevsner’s surveys of British architecture, for example, relied on photographs to convey stylistic details that were otherwise difficult to express in text.

While historians of art and architecture honed these practices within the academy, the travel slideshow was developing for a broader public and, eventually, as a middle-class pastime. Travel slideshows emerged from the learned societies of the early 19th century, where geographical societies used painted slides to illustrate lectures about explorations and discoveries. Lecturers at the Royal Geographical Society, for example, initially relied on drawings, maps, and hand painted images transferred to glass slides. The advent of photography in 1839 gradually transformed these presentations. By the 1850s, explorers were beginning to use photography to document their journeys, though the cumbersome nature of early photographic equipment limited its use in the field. The Royal Geographical Society began collecting photographs in the 1850s, with Roger Fenton becoming its first official photographer in 1852. Photographic slides became increasingly common over subsequent decades. More portable cameras and dry-plate photography made it more practical for explorers to document their journeys photographically. When the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888, photography was already central to its mission of documenting the world. Starting with their 1896 volume, the National Geographic Magazine styled itself as an “illustrated monthly,” featuring photographs of distant lands and peoples and cementing the relationship between travel and photography.

Through the early decades of the twentieth century, the lantern slide lecture gradually moved beyond elite scientific societies and universities to broader cultural institutions. Libraries, local history museums, and civic organizations regularly hosted slide-based travelogues, as did camera clubs and photographic societies. The Eastman Kodak Company recognized and encouraged this democratization of travel photography, developing increasingly portable cameras and, in 1934 introduced 35mm still film in daylight-loading cassettes with Kodachrome color slide film coming two years later. World War II accelerated this transformation as millions of American servicemembers traveled abroad, many carrying 35mm cameras and returning with images of far off places that they shared with their communities.

By the 1950s, travel and photography had become inextricably linked for the American middle class. The postwar economic boom made both more accessible: the 35mm camera became a standard possession while paid vacation time and the interstate highway system created new possibilities for travel. Even as international trips remained expensive, they were no longer the exclusive domain of the wealthy. A middle-class family might save for years for a single European tour, but such trips were now conceivable. The Kodak Carousel slide projector, introduced in 1961, allowed travelers to more easily show color slides at social events by eliminating the need to hand load slides. Living rooms would be transformed into makeshift theaters as neighbors gathered to see images of the Grand Tour, now documented in Kodachrome. Travel slideshows became a form of cultural capital, letting middle-class Americans demonstrate their sophistication while sharing their experiences with those who couldn’t afford to travel themselves. In practice, however, many amateur slideshows were guaranteed to induce sleep in darkened living rooms, and were often dreaded by invitees.

In Soviet Lithuania, slide lectures were rare and highly anticipated events, offering glimpses of the Western world. For example, the Nasvytis brothers—leading architects who served as professors at the Vilnius Civil Engineering Institute and had gained enough trust from the authorities to occasionally travel abroad—would organize presentations. Only a select group could attend: other architects and professors, cultural figures deemed ideologically reliable, and students whose records suggested they would not cause trouble. Knowing that the presentations were monitored for ideological conformity, the brothers carefully curated these presentations, selecting images that could pass official scrutiny while conveying developments in Western architecture. They had to maintain a delicate balance, showing enough to educate but not so much as to suggest the superiority of Western achievements. Such presentations were part of a broader pattern in which certain cultural figures—primarily established artists, architects, and academics who had demonstrated loyalty to the system—were permitted limited engagement with the West, always with the understanding that this privilege could be revoked.

The shift from careful documentation to ubiquitous capture traces the rise of photography into oversaturation. When the Kodak Brownie democratized photography in 1900, it remained a deliberate act—each image had to count. Even as production grew—from one billion photographs annually in 1930 to ten billion by 1970—photography retained its role as the intentional documentation of significant moments and places. The development of Kodak’s inexpensive, easy-to-use, but low-quality Instamatic in 1963, followed by Polaroid’s SX-70 in 1972, and Fujifilm’s disposable camera in 1986 all contributed to the rise of more casual—and more frequently taken images—but it took the arrival of digital photography, smartphones, and finally the launch of Instagram in 2010 to transform our relationship to images entirely. We now produce more photographs every day than were taken in entire years of the pre-digital era. With 1.3 billion images shared daily on Instagram alone, photography has moved from documentation to constant ambient production, from captures of the significant to an endless stream of the everyday.

I have repeatedly asked myself if, having left the academy behind for independent practice, I have merely joined the endless ranks of tourists. And even if I now travel like my father, for ideas for my art and writing, what does it mean to photograph buildings when likely as not, one can find similar—or better—images on the Internet with a simple search? The methodical documentation that characterized architectural history—the careful positioning to capture essential details, the systematic recording of building elements—seems increasingly disconnected from contemporary practice. Where Pevsner and Summerson’s photographs served as both evidence and analysis, today’s architectural photography operates in an environment of infinite reproducibility and instant access. Academics can just download images from the Internet instead of making pilgrimages to the monuments. The photographer’s craft, once essential to architectural history, has been simultaneously democratized and devalued by digital abundance. Slide libraries have been liquidated, just as card catalogs have been hauled to the landfill. And what of the tours of architecture, led by historians and organized by the Society of Architectural Historians as well as so many universities and museums? Are these research or tourism? What of the visits to other cities we make under the aegis of “research” for exhibitions, such as my visits to Hong Kong for the 2014 MoMA “Tactical Urbanism” show? What about botanical photography? Am I really doing any good, hiking with iPhone in hand, documenting species with iNaturalist?

The lines between scholarly documentation and tourist snapshot, between analysis and consumption, between purposeful recording and compulsive capture, have blurred to the point of disappearance. When every angle of every significant building is already available online, what distinguishes the architectural historian’s photograph from the tourist’s? Perhaps only the increasingly quaint notion that our images might contribute to some larger project of understanding.

In reflecting on the Grand Tour and its modern counterpart, I see a fundamental shift in how we relate to the act of travel. The Grand Tour was predicated on the idea of cultivation—of educating oneself through prolonged exposure to other cultures and histories. Today’s tourism, in contrast, seems predicated on consumption. We no longer seek to deepen our understanding of the places we visit; instead, we literally consume them by reducing them to a set of aestheticized images and move on.

The tourist photograph functions as a contemporary Claude Glass—a way of transforming reality into something consumable, shareable, and aesthetically pleasing. Sites like the Pantheon, the Eiffel Tower, or Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Shrine are now experienced through the screen of the smart phone, just like the social media the images are destined for. As visitors line up to take their photos, these sites become less about personal exploration or historical engagement and more about capturing a replicable moment, one that will be instantly validated by likes and shares on social media. How can one even see these sites anymore?

But it isn’t only the immediate experience that is threatened by the image, the actual memory of the experience is as well. Neuroscientists call this phenomenon the “photo-taking impairment effect”—the act of capturing an experience outsources its memory to the device, leaving the mind empty. In focusing on documenting the moment, we lose the cognitive and emotional engagement necessary to form lasting memories. What remains is a shallow trace of the experience, stripped of reflection and depth, replaced instead by the image itself. This phenomenon parallels the experience of Piranesi’s tourists, who arrived in Rome clutching engravings of ruins they had never seen, only to find their imaginations already colonized by someone else’s vision. Just as these engravings predetermined their expectations, today’s Instagram feeds serve as the preordained script for how places must be seen, photographed, and shared.

This reduction of memory to image reshapes how we interact with cultural heritage. Instead of spaces for contemplation, we get backdrops for a personal brand. Every photograph becomes both a proof of experience and a barrier to engagement, perpetuating the very oversaturation that alienates us from the spaces we visit. Even as these sites gain visibility, their existence dissolves into the noise of infinite replication.

In this way, modern tourism can be seen as both a continuation and a departure from the Grand Tour. The framework of travel remains—the movement through culturally significant sites, the desire to encounter the foreign—but the internal experience has changed. What was once a journey of intellectual and personal enrichment has become an exercise in superficial documentation. The modern tourist moves quickly, capturing images and moments to be shared, but rarely pauses to reflect on the experience in any lasting way.

While the transformation of tourism offers perhaps the most visible manifestation of this cultural condition, oversaturation extends far beyond the overcrowded sites and Instagram-optimized viewpoints that characterize contemporary travel. As I suggested for the symposium over a decade ago, oversaturation describes a state where systems of cultural production exceed their capacity for meaningful absorption or engagement—but it manifests as more than mere excess. It emerges when the imperative to produce overwhelms the possibility of reception, creating a peculiar state where increased production actually diminishes the capacity for meaningful engagement. We see this not just in overtouristed sites where crowds make it impossible to truly see a monument, but across all domains of cultural production: in the academic world where more papers are published than could ever be read, in an art market where more exhibitions open each night in any global city than anyone could possibly attend, in media landscapes so crowded that attention itself becomes the scarcest resource. The tourist’s compulsion to document rather than experience mirrors the academic’s pressure to publish rather than think, the artist’s need to exhibit rather than develop, the writer’s push to post rather than reflect. In each case, the system demands constant production while making deep engagement increasingly impossible.

Potential responses to oversaturation seem to fall into predictable patterns that ultimately reinforce the system they aim to resist. Consider how movements like slow food, farm-to-table, and local food initiatives, while seeking to resist global homogenization, actually intensify certain forms of tourism and consumption. The small local restaurant becomes internationally famous precisely for being local, drawing food tourists from around the globe who take shots of the careful plating for social media. The farm-to-table movement creates new forms of destination dining where the “authentic” local experience becomes more hyperlocal than the local ever was in the first place. A neighborhood pasta maker in Bologna or a tiny sushi restaurant in Tokyo becomes a mandatory stop on global circuits of food tourism, their very resistance to globalization transforming them into nodes in global networks of consumption and content production. Any tie to local culture is, ultimately, gone.

Former practices of resistance have been absorbed into this system of cultural oversaturation. The Situationists’ dérive—their practice of aimless urban wandering—has been commodified into “off the beaten path” tours advertised on Airbnb Experiences. Psychogeography becomes Instagram “hidden gems” guides. Even urban exploration, once a transgressive practice, has been transformed into “ruin tourism” complete with designated photo spots and hashtags. Anyone can take a tour of Chernobyl, with time for plenty of photographs. The system doesn’t just resist critique—it metabolizes it, transforming opposition into content.

Oversaturation produces spaces where physical and digital presence create reinforcing cycles of visibility. Consider how a single viral photo can transform an obscure location into a must-visit destination, generating more photos, more visibility, more visitors, until the original site is completely transformed by its own fame, destroying the very qualities that made a place attractive in the first place—a quiet beach becomes crowded with influencers, a contemplative temple becomes a selfie backdrop, a local café becomes a tourist trap.

Consider Les Deux Magots in Paris, once a revolutionary intellectual hub of the avant-garde, now one of the city’s most notorious tourist traps. The preferred café of Surrealists like André Breton and writers like Simone de Beauvoir, where artists and existentialists engaged in heated debate, it now serves primarily as a site of cultural performance where tourists can cosplay at being Parisian intellectuals. The café’s fame as a site of cultural production ironically destroyed its capacity to produce culture, replacing genuine intellectual exchange with its simulation. Yet even this transformation has become content —the café’s website proudly markets its history of artistic patronage, turning its own commodification into a selling point. Here we see how oversaturation operates across time: the cultural capital accumulated by generations of artists and intellectuals becomes transformed into tourist capital, which then generates its own forms of content about the loss of authenticity.

This transformation—from site of cultural production to site of cultural consumption— exemplifies how the drive for content creation has begun to exhaust not just physical spaces but cultural forms themselves. Just as overtourism can destroy the very qualities that made a destination attractive, cultural oversaturation depletes the meaning-making capacity of our systems of cultural production. When every moment must be documented, when every experience must be shared, when every observation must be transformed into content, we begin to lose the ability to distinguish between meaningful cultural engagement and mere performance of engagement. The documentation imperative becomes a form of cultural strip-mining, extracting content value while depleting the underlying capacity for meaning.

This oversaturation manifests across multiple domains: in the glutted academic job market where PhDs far outnumber available positions, in an art world where more exhibitions open each night than anyone could possibly attend, in conferences nobody attends, in media landscapes so crowded that attention itself becomes the scarcest resource. Yet production continues, driven by institutional imperatives and professional requirements that seem increasingly disconnected from any meaningful measure of impact or engagement. The academic must publish, the artist must show, the tourist must document—not because these activities serve any clear purpose, but because stopping would mean becoming invisible in a system in which visibility is everything.

This is oversaturation. Tourism is merely the most visible symptom of a broader condition—one where systems of cultural production have exceeded their capacity for meaningful absorption or engagement. The system demands constant production while simultaneously making meaningful engagement with that production increasingly impossible. What emerges is a kind of cultural attention deficit disorder—a system that requires overproduction to maintain itself while ensuring that no single piece of content receives too much sustained attention. The constant flow of new content keeps users engaged while preventing any single piece of content from demanding the kind of sustained attention that might interrupt that flow. The tourist moves quickly from site to site, the academic skims rather than reads, the art viewer passes briefly through exhibitions. This, not cinema (pace Benjamin) is how art is perceived through distraction today.

The virtualization of physical space creates new forms of cultural geography. Sites are no longer organized around historical or cultural significance but around their potential for content production. The “most Instagrammable” spots become the new centers of cultural gravity, while spaces resistant to photographic reproduction—however historically or culturally significant—fade into obscurity. This reorganization of space around platform logic produces a topography organized not by physical or cultural features but by the ability to generate engaging content.

The parallels between academic metrics and social media validation reveal a deeper convergence in contemporary culture. Just as scholars carefully time their paper submissions and cultivate citation networks, tourists and influencers optimize their posting schedules and build engagement pods. Both systems create eerily similar behavioral patterns—strategic timing, network cultivation, content optimization—homogenizing all forms of cultural validation into a single, universal metric of attention. The academic h-index and the influencer engagement rate become functionally equivalent measures in an attention economy that increasingly fails to distinguish between forms of cultural capital.

This homogenization of cultural metrics points to a broader crisis in how we assign and measure value. When everything must be quantified—from tourist footfall to citation counts to social media engagement—we create systems that inevitably demand more production, regardless of whether that production serves any purpose beyond feeding the metrics themselves. But how do you critique a system of overproduction from within institutions that require constant production to justify their existence?

The smartphone emerges not just as a tool of documentation but as both metaphor and mechanism for this condition. Just as it collapses the temporal stages of tourist experience into a simultaneous present of planning-experiencing-documenting-sharing, it also collapses traditional distinctions between producer and consumer, professional and amateur, meaningful contribution and mere content. The academic writes papers while scrolling through social media, the artist documents their process while checking their likes, the tourist experiences a place while planning how to present it—all participating in a system of continuous partial attention that paradoxically produces more while experiencing less. What’s particularly striking is how institutional responses to oversaturation often exacerbate the very conditions they claim to address. Universities respond to the glutted academic job market by creating more temporary positions, demanding more publications, and creating more documents to fill out. Art institutions address declining attention spans by programming more shows, more events, more content from the usual suspects. Tourist sites manage overcrowding by implementing time-slot systems and virtual queues that transform experience into yet another form of scheduled content consumption. Each solution feeds back into the system of overproduction, creating what we might call “saturation spirals”—self-reinforcing cycles where attempts to manage oversaturation just lead to exponentially higher amounts of it.

This system creates new forms of professional precarity that span seemingly disparate fields. The adjunct professor piecing together teaching gigs mirrors the gig economy worker managing multiple car-share platforms, the artist maintaining visibility across multiple venues echoes the influencer juggling multiple social media accounts. All are caught in a saturation spiral, facing the necessity of constant production and self-documentation not for any intrinsic purpose but merely to maintain visibility within oversaturated systems.

The relentless drive for content creation has begun to exhaust not just physical spaces but cultural forms themselves. Just as overtourism can destroy the very qualities that made a destination attractive, cultural oversaturation depletes the meaning-making capacity of our systems of cultural production. When every moment must be documented, when every experience must be shared, when every observation must be transformed into content, we begin to lose the ability to distinguish between meaningful cultural engagement and mere performance of engagement. The imperative to document becomes a form of cultural strip-mining, extracting content value while depleting the underlying capacity for meaning.

These examples point to a fundamental transformation in how cultural value is produced and consumed. The local restaurant that becomes a global destination, the academic paper that circulates more as a citation than as a text to be read, the artwork that exists primarily as social media content all reflect a system where the metrics of attention have become more meaningful than the cultural experiences they supposedly measure. The irony of oversaturation is that it produces not just an excess of content but a scarcity of attention, creating an attention paradox where increased production leads to decreased engagement.

This paradox manifests differently across domains but follows similar patterns. In academia, the pressure to publish leads to the slicing of research into “least publishable units,” creating more papers but less comprehensive analysis. In the art world, the proliferation of biennials and art fairs creates a constant cycle of production and display that is strongly proscribed to avoid either failure or success and leaves little time for artistic development or critical reflection. In tourism, the race to document and share experiences prevents the very forms of engagement that might make those experiences meaningful. Each domain faces its own version of the same crisis: how to maintain relevance in a system that demands constant production while making sustained attention increasingly impossible.

The institutional structures that emerged to support cultural production—universities, museums, publishing houses, tourism bureaus—now find themselves generating content to justify their existence, even as that content contributes to the very oversaturation that undermines their original purpose. The university must produce more research, the museum must mount more exhibitions, the publisher must release more titles, the tourist site must accommodate more visitors—each institution caught in a cycle of expansion that seems increasingly divorced from any meaningful cultural purpose.

What makes this condition particularly difficult to address is how it transforms even failure into content. The unfilled academic position becomes data for studies on the job market. The overlooked artwork becomes evidence of systemic inequality. The overtouristed site becomes fodder for articles about overtourism. The system doesn’t just resist critique—it metabolizes it, transforming opposition into content that feeds back into the very systems being criticized. Even this very analysis, attempting to understand the condition of oversaturation, necessarily participates in the production of content about overproduction.

Perhaps the most telling symptom of oversaturation is how it has begun to exhaust our capacity for imagination itself. The constant demand for new content, new experiences, new forms of engagement leaves little space for the kind of slow, cumulative development that genuine cultural innovation requires. We find ourselves in a strange temporal loop where the future becomes increasingly difficult to imagine precisely because we’re too busy documenting the present to reflect on where it might lead.

As forms of resistance become questionable, the academic who writes about the need for fewer publications still needs to publish that critique to ensure professional advancement. The artist protesting the commodification of art still needs to show in galleries and build their social media presence. The tourist seeking “authentic” experiences creates new circuits of authenticity tourism. The rejection of my proposed symposium on oversaturation now seems inevitable—not because the topic wasn’t important, but because addressing it would have required institutions to confront their own role in producing the condition. Universities, with their emphasis on global reach and quantifiable outputs, have become key drivers of cultural oversaturation. The academic system’s demand for constant publication, the pressure to maintain global networks, the emphasis on measurable impact—all contribute to the very processes the symposium would have critiqued.

The result is a kind of cultural vertigo where we can no longer distinguish between meaningful cultural production and mere content generation. When everything becomes content—from the tourist’s snapshot to the scholar’s research, from the artist’s process to the influencer’s post—we lose the hierarchies and frameworks that once helped us evaluate cultural significance. This flattening of cultural production creates a crisis of meaning not because meaning has disappeared, but because the systems we’ve built to produce and circulate cultural content make it increasingly difficult to distinguish what matters from what merely exists.

This condition raises fundamental questions about the future of cultural production. How do we maintain the possibility of depth in a system designed for constant circulation? How do we preserve spaces for reflection in an economy of attention that demands constant engagement? How do we resist the imperative to produce when visibility itself has become a form of survival? These questions become particularly urgent as artificial intelligence promises to accelerate content production even further, creating new forms of automated oversaturation that exceed our current capacity to even imagine.

The future that emerges from this condition seems to point in two contradictory directions. On one hand, we see the potential for ever-increasing acceleration—more content, more platforms, more metrics, more demands for attention. AI-generated content, automated curation, algorithmic recommendation systems all promise to increase production while further diminishing the space for human attention and reflection. The tourist of the future might navigate through augmented reality overlays, experiencing places through layers of digital content while generating new content through automated systems. The academic might publish in real-time, their thoughts instantly transformed into citable units of content. The artist might become primarily a curator of AI-generated variations on their style. What can exist beyond the event horizon of a “saturation singularity”—a point where the sheer volume of content production creates a gravitational collapse of culture?

To conclude, I’d like to reflect on my own relationship with photography, after some experimentation with photography in college, I returned to it as a graduate student in the history of architecture, producing a library of some 15,000 images for teaching, but this was a purely documentarian effort. I began to more consciously photograph landscapes—or rather human activity within them—when I worked with the Center for Land Use Interpretation in the late 1990s. But the Center’s approach to photography was studiously anti-photographic, deliberately eschewing the aestheticized vision of landscape photography in favor of what Hardin Farocki might called “operational images.” While clearly influenced by Bernd and Hilla Becher’s systematic documentation of industrial structures and the deadpan approach of New Topographics photographers like Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams, CLUI’s photography pushed further toward pure documentation. Their photographs functioned more as visual data than art objects, cataloging human interventions in the landscape with an almost bureaucratic neutrality. This approach—treating photography as information rather than expression—aligned with their broader mission of understanding how humans use and transform land.

The Center’s method suggested that even the most prosaic image could reveal something significant about our relationship to landscape if properly contextualized within larger systems of land use. Their Land Use Database, for instance, collected thousands of workmanlike photographs of sites ranging from military installations to mining operations, waste facilities to water infrastructure. Each image served as a data point in a larger investigation of how we shape, and are shaped by, our environment. This approach resonated with my own growing interest in infrastructure and its role in shaping urban space. Such a method of “anti-photography” offered a way out of both the romanticism of traditional landscape photography and the self-conscious artistry of much contemporary work. It proposed that the most revealing images might be those that appeared least obviously photographic.

Later, my approach to photography changed further when I reconnected with architect and longtime family friend John Vinci in Vilnius, Lithuania around 2000. Vinci, who taught history of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, introduced me to the technical precision of the Contax G2 rangefinder. Inspired, I acquired a G2 for myself, as well as a G1 loaded with black-and-white Scala slide film as a backup for when, inevitably, the G2 would break and have to go back to Japan for repairs. While the influence of CLUI’s operational imagery and its documentarian, even bureaucratic approach to infrastructure remained central to my practice, the technical capabilities of the Contax allowed me to expand my focus. I began to explore spatial and material conditions with greater intensity, pushing beyond neutral documentation toward a more intensive examination of spatial and material conditions.

These new tools and techniques empowered me to refine my visual methodology, which I first showed in my books Blue Monday and The Infrastructural City, both published with ACTAR. In these projects, my photographs continued to examine buildings and infrastructural landscapes, yet I brought a heightened attention to surface, texture, and detail. Despite this added focus on materiality, I maintained a distance from the dramatic, polished perspectives that dominate architectural photography. Avoiding the heroism and theatrical lighting often associated with commercial architectural photography, I opted instead for a more analytical detachment that positioned the structures as embedded within, rather than separate from, the broader urban systems they were part of. This approach allowed me to document the built environment without romanticizing it—photography became a tool for investigation rather than mere aesthetic representation. My framing then was carefully neutral, presenting the structure frontally but without attempting to monumentalize it. This approach draws from both the systematic documentation methods of the Bechers and the emphasis on contextual relationships that characterized the work of photographers like Lewis Baltz, but pushes toward a more deliberately ordinary presentation that reveals how buildings actually exist within urban systems.

Most recently, in my “Wastelands” project, I set out to document the overlooked and forgotten spaces of the state, focusing on the collision between infrastructural, industrial, and residential uses with a former glacial lake that has both uninhabitable areas and a tendency to flood at inopportune times. This work reflects my attempt to resist the attention vortexes of contemporary culture by concentrating on spaces that exist outside the circuits of content production. Again, I hope to avoid both the dramatic or aestheticized presentations common in photography, creating an alternative to the endless stream of highly curated images that dominate today’s visual world.

But it’s also a relatively natural impulse to want to document what I see, to record it as a memory, a memento or souvenir even, notwithstanding the photo-taking-impairment-effect. This summer, starting in Riga and continuing through Tallinn and then France, I experimented with a strategic form of imperfection using a disposable camera lens mounted in a plastic lens body to create images with inconsistent focus and strong vignetting. These monochrome images create a deliberate distance from both the hyperrealistic imagery of the iPhone and the precision of the 60mp mirrorless Sony alpha, recalling instead some earlier forms of travel photography. The technical limitations become a form of temporary resistance to oversaturation—the images resist easy reproduction, refuse the logic of instant shareability, and create moments of uncertainty that demand slower, more careful viewing.

This experimental photographic practice embodies the very paradox that my proposed symposium would have explored: how to critically examine a system of overproduction while necessarily remaining implicated within it. Where that academic initiative was stymied by institutional constraints, these photographic strategies offer a temporary mode of investigation—one that acknowledges its contingent nature and makes no claims to escape the system, yet still strives for a momentary distance through deliberate technical choices and careful attention to method. While such resistance may be fleeting, perhaps these moments of defamiliarization, of slower, more considered engagement suggest possibilities for individual responses to oversaturation.