We stopped for lunch at a Connecticut rest stop on the way out to Rhode Island two weekends ago and I ate at Chipotle. Three days later, I was back at home with a new friend, Campylobacter. I wasn’t able to get my planned post out and this one, which was supposed to be a brief, little piece now covers 25 years of blogging and 30 years of having a Web site. No longer brief, at 8,400 words long, it’s the longest piece I have yet put on Substack to date, although in fairness, it does contain a full blog post by Lebbeus Woods inside of it. In the end, this is my most thorough reflection on my life on the net as well as my life as a blogger.

I should be back to a relatively normal schedule soon. In the works: another essay for the Skeptic’s Guide to AI and Art and more writing for the Florilegium. I should also work on my taxes.

As always, you can read this on my blog, https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/on-the-golden-age-of-blogging/. I’ve worked a lot on the design https://varnelis.net. Do take a look if you haven’t been. Finally, please do reblog, share, and like this piece if you enjoyed it or learned something from it. As long as my site sees more traffic and my Substack sees more growth, I’m a happy blogger.

In the April 3 episode of the Dwarkesh podcast, Scott Alexander (of SlateStarCodex fame) lamented: “I am so mad at myself for missing most of the golden age of blogging. I feel like if I had started a blog in 2000 or something, then—I don’t know, I’ve done well for myself, I can’t complain—but the people from that era all founded news organizations or something. I mean, God save me from that fate. I would have liked to have been there. I would have liked to see what I could have done in that area.”

As someone who participated in it directly, the reality of early blogging bears little resemblance to Alexander’s mythologized version. Still, prompted by Alexander’s romantic musing, I thought it worthwhile to spend a few days engaged in a kind of digital archaeology, excavating three years of my early blog posts (2000–2003) from an old hard drive, then converting and uploading these posts to WordPress. So this is not a single post, it’s 377 posts. All of these—save, of course, this one, another 8,000-word long-form monster that took three weeks to write, the sort of thing a 57-year-old produces looking back at days that, in retrospect, seem a whole lot better than they were—are brief, a link with a sentence or two of commentary, nothing more. This sort of blog—and indeed all blogs—evolved from “What’s New” pages, which were standard features on early websites. NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications)’s site, maintained by Mosaic (the first real web browser) developer (and present-day Venture Capitalist and right-wing extremist) Marc Andreessen included such a “What’s New” page, tracking new sites appearing online from June 1993 to June 1996, cataloging everything from fan pages on the TV show The Prisoner hosted at the University of Limerick to the South Bay Ski Club.

These early proto-blogs were remarkably minimal: brief updates, link collections, and fragmentary observations rather than the developed essays that define contemporary blogging. Justin Hall’s online daily diary, launched in December 1994 when Hall was still a high school student, pioneered personal disclosure online, creating an intimate window into his life that differed significantly from the curatorial approach of other early web pioneers. Justin’s diary was something of a real-life digital Dawson’s Creek, captivating for many readers.

In contrast, sites like Dave Winer’s Scripting News and John Barger’s Robot Wisdom (both in 1997) functioned more as a form of Internet DJing: brief observations, often snarky, sometimes just a link with a one-line comment—a far cry from the long-form posts that characterize contemporary blogging. Robot Wisdom, running on Winer’s complicated Frontier’s NewsPage software and where Barger coined the term “weblog,” exemplified this DJ mentality with its eclectic collection of links and brief commentary. Just as I would do, these early bloggers functioned primarily as curators rather than producing sustained arguments. The blog post as we know it today—a self-contained essay with developed arguments and sustained reflections—was still years away from emerging as the dominant form.

What united these diverse early web pioneers—from Hall’s confessional diary to Winer and Barger’s curatorial platforms—was a distinctive rhetorical approach that diverged sharply from institutional communication. They (We) employed an informal, conversational tone that established a direct relationship with readers—creating the sense of accessing an insider’s perspective. “Snark”—that knowing, ironic distance that signals the writer’s superior understanding of a situation—became a hallmark of this emerging style. This rhetorical strategy—common to Zines and to the Punk aesthetic that ruled the counterculture at the time—positioned the writer as a savvy guide cutting through official narratives to reveal a more authentic, personal truth. Unlike traditional media’s affected neutrality, these early web writers embraced subjectivity, making their positions and preferences explicit, often with cutting wit and cultural references that their intended audience would have understood.

Blogging was, above all, personal. So, with that in mind, permit me a digression into my personal experience and how it paralleled the experience of blogging. As a high school student in the early 1980s, I sold articles about programming the Commodore VIC-20 to magazines like Compute! and Creative Computing, and though these pieces never saw print, they provided crucial income for a teenage programmer. I was involved in BBS culture in the early 1980s, but only as an occasional user: my parents weren’t about to let me have a modem on their precious phone lines. During my early college years at Simon’s Rock (1984-1986), I ran a one-man software company, writing an expansion to the BASIC programming language that gave the VIC-20 the ability to draw rudimentary graphics such as circles and lines. I also wrote code for a friend’s software company that used UNIX machines. At the same time, I took a course in journalism with Andrew Pincus, journalist and music reviewer at the famous Berkshire Eagle. I was fascinated by the New Journalists Andrew introduced us to—Truman Capote to Tom Wolfe to Hunter S. Thompson—and the idea of saying utterly unacceptable things in print. It got me called into the Provost’s Office more than once. Unfortunately, when I joined the History of Architecture program at Cornell, I had less time for either tech or journalism. Compounding this, Cornell Information Technology standardized on the Macintosh campus-wide and while the Mac had a revolutionary interface, part of that magic was that it was deliberately difficult to program; the first Mac was intended as an appliance for professionals, not a hobbyist’s computer and was priced accordingly, costing $2,495 ($7,600 in 2024 dollars). This began a long hiatus from coding that only ended in the 2010s when I started to integrate tech and art. Nevertheless, appliance or not, I was fascinated by the emerging technologies of the day. At Cornell, I was able to use the Internet to regularly send e-mail to friends at other campuses and browse USENET for the first time, a natural evolution of my interests. I remember using Fetch, an FTP program to download software from the Funet software repository in Finland in 1989, marveling that my keystrokes were making a hard drive head halfway across the world seek some obscure sector I had selected.

In the summer of 1993, I witnessed firsthand the potential of the World Wide Web through an early version of the NSCA-Mosaic browser running on a SUN workstation. The Honolulu Community College’s “Dinosaurs in Hawaii” exhibit—one of the first fifty websites ever created—left me stunned with its (now primitive) integration of imagery and text on a page—more like a book or magazine as opposed to a command line interface or the interface of the competing Gopher system, something of a hybrid between a Hypercard stack and a set of file directories. My initial explorations were using the primitive MacWWW browser both at Cornell’s public computer labs and via the 14.4k US Robotics “Sportster” modem I had in my apartment, but once NCSA released the Mac beta of Mosaic in September 1993, I adopted it immediately, even earning a mention in the first Mac press coverage of the browser’s release.

By spring 1995, I had established my own hand-coded HTML website, a painstaking endeavor in the dial-up era where each update or correction required a lengthy time uploading to the FTP site, followed by checking on not one, but many, browsers (Microsoft Internet Explorer lagged behind web standards and was notorious for always failing to render a web site correctly). It also hadn’t been easy to find a web host. Hosting Internet sites was not easy and until I subscribed to the local Internet service provider—Homer Wilson Smith’s Lightlink, I had no way to put up anything on the Internet.

My first site was not much more than a curated collection of online architecture and humanities resources, a specialized directory or landing page for links that I used and expected others would want to use as well, plus “The Lair of the Chrome Peacock,” a page dedicated to the use and maintenance of the La Pavoni line of espresso machines. Like most early web users, I visited “What’s New” aggregators such as MacInTouch, which gathered scattered news from across the Internet and provided brief editorial commentary daily starting in 1994. This was, once again, the site proprietor as Internet curator/DJ, laying down a pattern of links and commenting on them daily. In the spring of 1996, I developed an idea for a web site titled “ARC * Wire,” “both a central clearinghouse for news on architecture and … a forum for new design work, theory, and criticism.”1. Not only would this site aggregate all new architecture links, I hoped it would also serve as a journal, even a successor to the 90s theory journal Assemblage, which was rumored to be finishing its run soon. I talked with some friends like David J. Lewis, then working at Princeton Architectural Press, and C. Greig Crysler, then editor of the Canadian architecture journal A/R/C about various ideas—including for a SPY Magazine style parody site called Cranked or 13th Floor, but again, the technical challenges were high, seemingly insurmountable.

I brought that idea with me after joining the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI_Arc) faculty in 1996. In March 1997, I was invited to a meeting at SCI_Arc with Paul Petrunia, then an undergraduate architecture student at the school and a nascent web developer, together with the school’s publications team to discuss replacing SCI_Arc’s static website—just a single image with a few footer links, not even utilizing the basic imagemap functionality common at the time. I proposed a revamped version of ARC * Wire called SCI * Arc * Wire (I uncovered the original proposal, time-stamped March 22, 1996, and posted it here) to transform the site into what would have not only been the first architecture blog but also a dynamic news platform that would have positioned SCI_Arc as not just a physical institution but as a global digital nexus for architectural discourse. My concept extended beyond mere updates to include a comprehensive archive of faculty works as well as invited essays in a journal format, effectively creating an authoritative online architectural publication establishing the school as an intellectual leader in digital space, rivaling Columbia’s GSAPP and the Architectural Association’s Design Research Laboratory. The school dismissed the idea and Paul agreed that it was likely technically unfeasible, a reasonable assessment given the era’s technology—it hadn’t worked out for me the previous year with ARC*Wire. Yet the concept seems to have resonated with him; that summer, he launched Archinect, which became architecture’s preeminent online hub, albeit without the academic focus I had intended for SCI * Arc * Wire. It was for the better, if the school had done it, the high degree of polarization there would have likely led to friction, controversy and an early dismissal from my job.2.

This pattern of dismissed ideas finding validation soon after became a recurring theme throughout the early web era, where technical limitations often temporarily delayed inevitable developments. The term “weblog” entered common usage in 1997 through Barger’s Robot Wisdom before being abbreviated to “blog”—a linguistic compression that, despite its inelegance, captured the medium’s emphasis on immediacy and informality. The true democratization of blogging arrived with Pyra Labs’ launch of Blogspot (now Blogger) in August 1999, which automated much of the technical drudgery that had previously limited participation. I launched this site in April 1998 as kazys.net. It was still a collection of links, but some of those links were now links to my essays. In May 2000, however, I successfully integrated Blogspot’s functionality into my site, marking my formal entry into what journalists were now calling the “blogosphere.”

In retrospect, I’m not entirely sure what my goals were in starting to blog, and this lack of clarity may have been a strength. Blogging represented the future, and like many others caught up in the era’s technological optimism, I wanted to participate in whatever that future might bring. Unlike many contemporaries gaining attention through confessional posting, I maintained boundaries between my intellectual work and personal life. I conceptualized my blog not as a diary but as a living archive of intellectual inquiry, a public workshop for developing ideas without academic publishing’s formal constraints. Instead, I conceived of the blog as a rolling record of intellectual preoccupations, a space for working through ideas in public without the pressure of formal publication.

Los Angeles became the central subject of many of these early posts, functioning as my laboratory for understanding emerging network structures. These entries—composed during brief intervals at home, at SCI_Arc’s computer lab, or via my PowerBook’s WiFi PCMCIA card between teaching obligations—formed an analytical portrait of a metropolis in transition. Los Angeles was evolving beyond its traditional identity defined by automobiles and entertainment into something more complex: a critical node within expanding global networks of capital, information, and culture. Through blogging, I could document this transformation in real time, without waiting for the slow machinery of academic publishing to validate these observations.

By 2003, my relationship with blogging had changed. The birth of Viltis, our first child, coincided with growing disillusionment with SCI_Arc, which under Director Eric Owen Moss had begun embodying the very architectural culture it once critiqued—becoming increasingly hierarchical, spectacle-obsessed, and hostile to critical reflection. Watching the institution drift from its radical origins toward conventional celebration of architectural celebrity and the ethical impropriety of working for the proto-Trumpian school director ultimately prompted my resignation in spring 2004. At the same time, blogging had become a bit of a chore. Who and what was I doing it for? I needed to take a break and I suspended the blog without notice—perhaps without knowing—at the end of July. Robert Sumrell and I worked on our growing radical architecture project AUDC, I enjoyed working more with the Center for Land Use Interpretation, became the President of the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design, a group that had the energy increasingly lacking at SCI_Arc, and in what free time I had, I plotted my next steps.

In fall 2004, I started Simultaneous Environments, a project mapping Los Angeles’s transformation from 1990 to 2005—charting its evolution from a city primarily defined by automobiles and Hollywood to one increasingly shaped by networked systems. This research eventually evolved into The Infrastructural City, which reframed Los Angeles through the lens of its exhausted infrastructures and stalled futures, while exploring potential responses to these conditions.

The next spring, Detlef Mertins invited me to spend the semester at the University of Pennsylvania, where my final attempt at securing a traditional history of architecture position collapsed under the weight of academic politics internal to the school. I redirected my interests toward more productive terrain. I spent the following year at USC’s Annenberg Center for Communications directing the Networked Publics project, running a team of scholars to investigate a topic that seemed very much of the moment. Recognizing our need for a collaborative platform, I taught myself the Drupal content management system in order to develop networkedpublics.org as a group blog. Knowing that this would be a challenge, I relaunched my personal site on the platform in May 2005.

By the time I returned to blogging, the architectural blogosphere had begun to take shape. Blogging offered a fundamentally new model of architectural discourse: informal, distributed, and networked writing operating outside established media channels. This emerging form functioned at a different cadence and register than traditional publishing—more immediate, conversational, and liberated from institutional gatekeepers. As disillusionment with conventional architectural criticism grew, the democratized access to publication allowed independent, critical voices to flourish with unprecedented speed.

Hyperlinking, the very core of the hypertextuality in HTML served as the structural foundation of this architectural blogosphere. My site, alongside platforms like Archinect and things magazine, utilized linking not merely as citation but as a fundamental architecture—creating pathways connecting architectural theory with digital media, technology, urbanism, and cultural critique. These hyperlinks functioned simultaneously as source documentation and conversation, weaving disparate topics into coherent networks. This interconnected structure mirrored the networked urban conditions many of us were analyzing—a digital form following intellectual function. RSS (Really Simple Syndication) had emerged (Aaron Swartz—whose death will always haunt MIT and JSTOR—was a co-developer of RSS), allowing individuals—or sites—to subscribe to feeds from multiple sites. With the release of the elegant NetNewsWire reader for the Mac in 2002, it became possible to have an aggregator that one could use to browse the news across multiple sites on one’s own desktop. Released in October 2005, Google Reader dominated the RSS market—even being used to provide aggregated feeds for desktop apps like Reeder, which became popular after NetNewsWire seemed to grow stale.

This networked structure of thought mirrored the networked urban conditions many of us were discussing—a form following intellectual function. By 2007 a vibrant architectural blogosphere had formed: Owen Hatherley’s Sit Down Man, You’re a Bloody Tragedy, John Hill’s A Daily Dose of Architecture (which actually originated in 1999 and is thus one of the first architecture blogs), Mimi Zeiger’s online extension of her legendary late-90s zine Loud Paper (the blog launched July 2007), Dan Hill’s City of Sound, Bryan Finoki’s Subtopia, Geoff Manaugh’s BLDGBLOG, Alexander Trevi’s Pruned, Enrique Ramirez’s aggregät 4/5/6, Adam Greenfield’s Speedbird, and Molly Steenson’s girlwonder all offered distinctive voices united by a skepticism toward the dominant architectural critics such as Nicolai Ouroussoff, Christopher Hawthorne, and Paul Goldberger, whose work primarily celebrated the “Bilbao Effect” and its proliferation of iconic buildings by celebrity architects.

Our resistance to architectural spectacle was collective, even if our tactics diverged. Owen pressed for a return to the egalitarian, even Communist, ethos of Britain’s post-war housing—what he later codified as Militant Modernism. Dan, Adam and I argued that real urban change would flow through broadband pipes, mobile networks, and APIs the soft circuitry governing streets more decisively than steel or concrete. Mimi channeled her Loud Paper zine into an online pamphlet that celebrated guerrilla exhibitions, pop detours, and what would later be called “tactical” interventions. Bryan compiled a field guide to military urbanism, tracking how border walls and carceral logics seep into everyday space. Geoff spun speculative tales of sinkholes, weather warfare, and underground worlds, recasting design as imaginative fiction. Enrique crafted deeply researched cine-spatial histories of oceans, flight, and media. Together we dismantled the Bilbao-era starchitect narrative from a dozen directions—left politics, network urbanism, zine culture, data infrastructure, martial geographies, landscape futures, and cinematic atmospheres. Critique thrived in polyphony.

In 2007, Lebbeus Woods launched his blog, an acknowledgment that the scene had become socially acceptable, even for established figures in architectural discourse. Lebbeus’s blog instantly rose to the top and he kindly engaged with the many students and young architects who were his fans until shortly before his death in 2010. And, unlike most avant-garde architects of his generation, he shared the anti-establishment ethos of the younger blogosphere. In writing of Jean Nouvel winning the 2008 Pritzker Prize, for example, he wrote (this is the April 1, 2008 blog post “Sic Transit Gloria,” in full):

Jean Nouvel has won the 2008 Pritzker Prize for Architecture. No surprise. The lack of surprise makes it is easy to view the Pritzker as establishment laurels for those who are already well-established. Like the Nobel Prizes, it is conferred on safe, already certified choices. Nouvel’s buildings are certainly of a high quality of design. At his best, he designs beautiful buildings. Who can quarrel? The Pritzker tries to remind us that the design of beautiful buildings within, or maybe—on occasion—closer to the limits of the accepted canon of beauty is the ultimate goal of architecture. People need enclosed spaces, and it is up to architects to design them in ways that satisfy the needs of body and soul. Or, at least, in ways that reassure us about what we already know. Nouvel works masterfully within the limits of what we already know.

So, is there a problem with any of this? Not at all. I say, let the rich bestow upon the famous whatever they like. Let the rituals of power play themselves out as they always have. It is quite a seductive spectacle. We all become part of it, say, by posting comments like this on blogs.

But I have to question how relevant the Pritzker Prize is for the expanding world of architecture. Whatever its claim to reward innovation and expand discourse, I would say not very. Its focus on buildings, and often expensive buildings, leaves out much of the most innovative work going on in the field today, by younger architects making smaller-scale projects, or experimental ideas that never get off the boards or out of the computer—ideas that get published and change our ways of thinking about what architecture is and can be. The Pritzker sends the message that unless one builds, and in a spectacular way, one will never qualify for “architecture’s top honor.” The catch-22 here is that to build you need clients, and to build spectacularly, like Nouvel, very rich clients, and they are seldom willing to risk sponsoring the genuinely new. So, the subliminal message is, don’t push the envelope too far.

The existence of the Pritzker reminds us that the powerful are not as self-assured as they like to appear. They need to engage continually in demonstrations of their power, such as getting on—in an upbeat way—the front page of the New York Times, as well as other major newspapers and magazines around the world. Oddly enough, the Times perennially rails against the Nobel Prizes, not least because its founder was an armaments manufacturer who bought respectability in posterity by creating prizes in his name for intellectual achievement. And it works. When we think of Alfred Nobel, his name becomes synonymous with Albert Einstein, Samuel Beckett, Toni Morrison, Martin Luther King, Jr. The Pritzker is sponsored by the Hyatt Foundation, not exactly “merchants of death.” Still, the formula works. By associating themselves with successful architects and the world of creative thought, they make a significant step up in cultural, and historical, terms. Their domain, and their power to affect the world, is extended and consolidated.

For the recipients of the Pritzker, it’s easy enough to understand why they would accept it, often with speeches of praise for the Prize and its sponsors. The money may be relatively paltry ($100,000, compared with the Nobel’s $1,500,000), but every bit helps and, after all, why not? What’s the harm? Only two have ever declined the Nobel, on principle: Sartre and Le Duc. So far, no architect has declined the Pritzker. If that were to happen, it really would ‘expand the discourse.’

All this we already know. So, why bother to write about it? Perhaps only to step back from the spectacle long enough to see its contour, and its limits. Only then is it possible to see its true place in the order of things, and the wider world that lies beyond.

LW

Unfortunately, at about this time, big, commercially-oriented blogs were established—notably ArchDaily and Dezeen. Part blog, part traditional media platform, these were professionalized, polished, and fluff-heavy, frequently aligned with marketing, project announcements, product placement, and sponsored content, devoid of independent voices, but perfect for the market. Their emergence marked the beginning of the transformation of architectural blogging from a space of critique to one of promotion.

The first discussion about blogs in architecture appears to be an April 2009 MIT panel I shared with Javier Arbona and Mark Jarzombek, titled “Blogitecture, or Architecture on the Internet.” I began my talk with a moment of reflection that holds up 16 years later: “I’m going to go back before the origins of architectural blogging … to the origins of the web and point out that I was there at the right time at many of these places and managed to miss every opportunity (almost).” At that moment, blogging had reached a crossroads—caught between its early promise of democratized critique and its emerging entanglement with the very spectacle it sought to evade. I noted that RSS feeds, comments, and trackbacks (in which one blog would notify another when it referenced it) broke the boundary between author and audience and transformed blogging into “a switching machine for data flows”—the Internet DJ now had the capacity for near-real-time feedback. This was a genuinely new form of writing and created the possibility of real back-and-forth dialogue among writers. Later that year I would participate in Helen Thornigton and Jo-Anne Green’s Networked: A (Networked) Book about (Networked Art) project, contributing a chapter to a book running on Commentpress, a fork of WordPress created by the Institute for the Future of the Book. The goal of this project being to create an open, interactive book in which readers could act as co-authors, leaving comments and creating a community-driven discourse while challenging the idea of the book as a static object.

Even as I celebrated the new technological transformation, however, I lamented that architectural discourse itself had slid from history to theory to criticism with both history and theory nearly extinguished while newspaper critics served mostly as publicists for what urban sociologist Harvey Molotch termed the “Growth Machine.” In an influential 1976 paper, Molotch described how local elites, developers, media, and institutions form coalitions to promote development regardless of actual public benefit—essentially viewing cities as machines for generating wealth rather than habitable environments.3. Architectural criticism had largely become subservient to this apparatus, celebrating spectacular buildings that served as capital magnets while ignoring broader urban conditions. Blogs, I felt, arrested that slide by giving dispersed voices a platform to challenge this hegemony, creating spaces for more critical, historically informed discourse outside the growth machine’s influence.

Javier, an architect and geographer, turned to statistics showing that bloggers were overwhelmingly affluent professionals; thus he explained, legal blogs flourished because lawyers possessed both the disposable time and the appetite for arguments about privacy and intellectual-property rights. Architecture blogs mirrored that class bias, he argued. and within architecture, authority followed a pyramid: sites like BLDGBLOG, Inhabitat, and Dezeen occupied the apex, their posts ricocheting through Archinect, Twitter, and Tumblr until even student blogs adopted the day’s talking points—such as open source, green, innovation— which had passed uninspected from Silicon Valley into design studios. Javier suggested that a discourse on labor rights was missing in the architectural blogosphere (oddly enough, such a discourse was about to take off, but wound up as a movement centered around Yale University, a questionable place to start a workers’ revolution). Arbona displayed A Daily Dose of Architecture‘s sidebar of abandoned blogs—a digital potter’s field—and rhetorically asked why enthusiasm so often curdled into silence.

But of course, if we both engaged in the all-too-predictable discussion about privilege in blogging, we were speaking from within the academy, a place of institutional security, if not comfort, that gave us both a voice and an audience. Our criticisms of spectacle, technology, and capital unfolded within the medium of an academic conference, a ritualistic site we naturally didn’t dare question, since being in the belly of the beast makes one reluctant to prod it. Blogging had promised to disrupt such privileged circuits—indeed, for a time it appeared it might. Take the potter’s field of blogs; is there anything wrong with giving something a try and then giving up on it? Or the argument that blogs are only for those with sufficient leisure time to engage in writing and the wealth to access the Internet? Reading, bowling, knitting, and Marxist activism are all leisure time activities only those relatively well off, on a global scale, can engage in. Why not, then, blog if that gives you joy and community? When it was fun, blogging was part of everyday life, not a form of labor. That sense of camaraderie, of participating in a distributed conversation that felt vital and immediate, was its own reward.

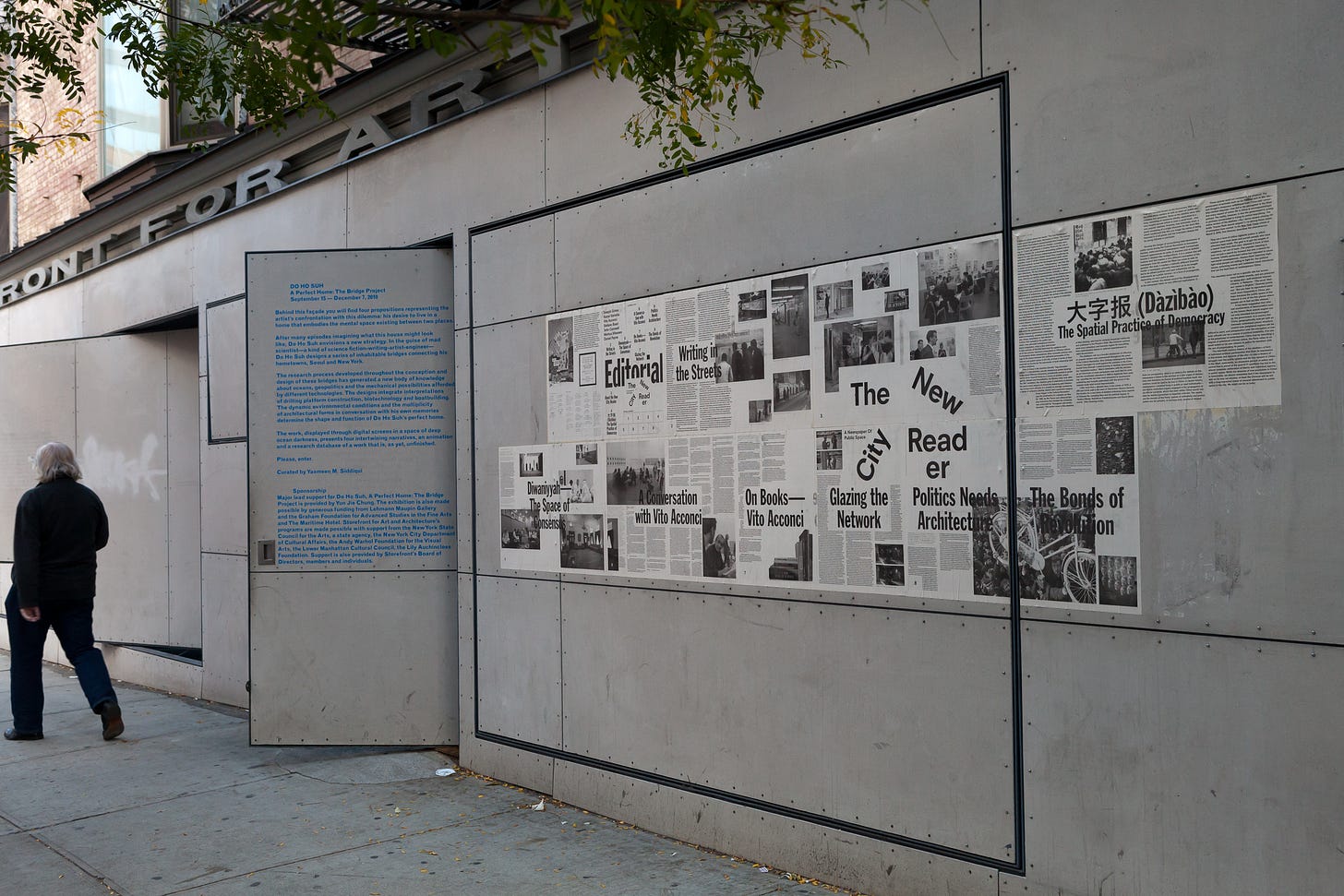

We took steps to mature as a critical movement. Mimi Zeiger organized an underground discussion group called LGNLGN which included virtually all the names mentioned so far, save Lebbeus Woods, and we sought to find ways to professionalize and expand our reach. In the end, the most substantive outcome was the New City Reader, a broadsheet newspaper co-edited by Joseph Grima and myself and published in 2010 as part of the Last Newspaper exhibition at the New Museum. This project represented an attempt to bridge the gap between online discourse and physical media, producing critical content that could circulate beyond the screen while maintaining the networked sensibility of blog culture.

But by the time the New City Reader was published, things had started to change. Just as the blogosphere reached its zenith of cultural influence around 2007-2008, social media began its ascent. Initially launched exclusively for Harvard College students in 2004, The Facebook opened up slowly, first to Stanford, Columbia, and Yale, then the whole Ivy League and downwards through the .edu hierarchy until it was accessible to the wider public in 2006. Dropping the definite article, Facebook reimagined online interaction through user profiles and explicit “friend” connections. Its defining innovation was the News Feed, an algorithmically curated stream introduced in 2006, aggregating updates from a user’s network, eliminating the need to proactively visit individual websites.

The launch of Twitter in 2006—co-founded by Blogger creator Evan Williams—marked another pivotal moment. Twitter pioneered “microblogging” with its 140-character (later 280) updates designed for real-time sharing. While Williams conceptualized it more as an “information network” than a social platform, its impact on attention flows was profound. The short, snarky posts that characterized early blogging found a natural home on these platforms, particularly Twitter, which seemed tailor-made for the Internet DJ mentality. But critics like Alexandra Lange observed that most architects—which isn’t the same as most bloggers—predominantly used these platforms for self-promotion rather than substantive discourse, missing opportunities for deeper engagement with the cultural implications of their work.4. Tumblr (2007) offered yet another variation, blending short posts, images, and links in a format closer to traditional blogging but still emphasizing brevity and multimedia content.

Facebook’s 2012 acquisition of Instagram for $1 billion marked a pivotal shift in online discourse, particularly for visually-oriented fields like architecture. Instagram’s image-first format fundamentally changed how architectural work was presented and consumed online. The platform’s emphasis on striking visuals, deemphasis on discussion, and its highly efficient distribution system accelerated what critics called “render culture”—where photogenic qualities often trumped practical considerations in architectural evaluation. For many architects and firms, Instagram became the primary platform for sharing work, with some projects seemingly designed more for their “Instagrammability” than spatial experience. This visual dominance particularly impacted architectural discourse, which had traditionally balanced textual critique with visual documentation. The “Like” button, introduced in 2009 further streamlined interaction, offering frictionless engagement but discouraging the substantive conversations that flourished in blog comment sections. These features created a compelling “walled garden” designed to capture and retain user attention within Facebook’s ecosystem. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter replaced the blog for many. Indeed, with the need to keep up with all three, and perhaps Tumblr, there was less time for blogging.

Discovery shifted from blogrolls and search engines to algorithmic feeds controlled by platform companies. Consumption habits changed dramatically, influenced by smartphones and mobile internet access, which favored bite-sized content consumed on the go. The Pew Internet & American Life Project documented a notable decline in blogging among younger demographics after 2006, coinciding directly with their adoption of social networking platforms.5.

Simultaneously, traditional architectural criticism started to collapse. The sycophancy of design criticism with regards to starchitecture, the speed and accessibility of digital platforms, a continuing decline in print readership, and a decline in newspaper finances caused by the rise of social media and Craigslist’s decimation of the advertising market contributed to less and less lengthy, rigorous critiques of the sort once found in print journals. Architectural analysis became increasingly fragmented, as the glossy, PR-driven sites Dezeen and ArchDaily took over. Unlike the independent blogs of the 2000s that frequently challenged dominant architectural narratives, these platforms largely reinforced them, prioritizing photogenic projects aligned with market trends, emphasizing aesthetic novelty and technological innovation disconnected from broader cultural or political contexts. This would soon be dubbed “Instagrammable architecture,” to refer to spaces or renderings conceived chiefly for shareable impact on an iPhone screen. Representation, especially in the schools, shifted to a pastel-toned isometric axonometry—a “post-digital” mode that fusing Archigram-style cartoons with Monument Valley-like pixel art. A 30-degree grid, uniform line weight, and flat vector fills equalize vending carts, solar panels, and structural bays, casting buildings as candy-colored storyboards. Dramatic stairs, chromatic backdrops, and razor-sharp geometries proliferated less for spatial experience than for social media potential. What resulted was an architectural discourse increasingly dominated by visual consumption rather than critical reflection—a pattern that has only intensified with subsequent platform evolutions.

Architecture itself reached an impasse by the 2010s. The problems that animated the energetic neo-avant-garde architecture of the 1990s and early 2000s—the return to modernism, the blob vs. the box, the pursuit of iconic buildings to trigger the ‘Bilbao Effect’, an architecture for the creative city, and the exploration of computational design’s potential for generating new material expressions—had been mined to death and exhausted. When these problems were seemingly ‘solved,’ architecture as cultural inquiry didn’t advance to new territory but instead floundered in a conceptual vacuum. Worse yet, from a philosophical perspective, architecture’s traditional proper object—the shaping of collective space—was now subsumed by computation itself. If computation had promised to revolutionize architectural form, it now redirected collective experience toward virtual spaces. Where young people interested in both art and technology once went into architecture, now they were lured in not only by the profits but also by the transformational promise of the Internet startup. The cure turned out to be the poison. The new commons ceased to be the plaza or the museum atrium and was now the space of the network, mediated through screens rather than physical structures. People, it seemed, could now only conceive of architectural space by taking selfies of themselves on Instagram. It wasn’t merely that architecture reduced itself to Instagrammable imagery; it was that architecture conceptually disappeared on Instagram, becoming merely another category of consumable visual content rather than a spatial art with social agency. Unlike previous moments of architectural crisis that generated theoretical breakthroughs, this exhaustion produced no corresponding illumination—only a sense of architecture’s increasing irrelevance to contemporary experience.”

Of course, as Hal Foster argues in his reading of the Freudian concept of Nachträglichkeit (deferred action) in The Return of the Real, cultural phenomena often operate through delayed recognition. The trauma or innovation registers initially without full comprehension, only to resurface later with renewed significance. Freud’s term suggests that meaning is assigned retroactively, as previously latent connections become visible. By this logic, the seemingly exhausted questions of architecture—how to shape collective experience, how to reconcile digital and physical realms, how to create meaningful intervention in increasingly privatized space—will likely one day return with renewed urgency under different conditions. But for now, architecture has entered a period in which it is for us, once again what Hegel would call “a thing of the past.” There is much to the idea of philosophy traveling through disciplines and to the recurrence of the death of architecture, but this digression is a matter for another essay.

Nor did starchitecture survive this period. According to Davide Ponzini, author of Starchitecture: Scenes, Actors, and Spectacles in Contemporary Cities, the symbolic significance of star architects declined markedly in the late 2010s. The death of iconic figures such as Zaha Hadid in 2016 further underscored this diminishing era, bringing to a close the dominance of a few celebrated architects like Frank Gehry, Norman Foster, and Rem Koolhaas. The cultural authority once held by these figures has significantly eroded, as critics increasingly challenged starchitecture for its extravagance, egocentrism, and inadequacy in addressing urgent environmental and social concerns. Ponzini suggests that these dramatic, spectacular buildings, often disconnected from their urban contexts, came to embody the contradictions and failures of urban development strategies that prioritized visual and symbolic impact over practical functionality, sustainability, and social inclusivity. Furthermore, as architectural discourse became fragmented across numerous digital platforms and diverse critical voices emerged, the unified cultural narrative and consensus that originally fueled starchitecture’s global prominence disintegrated.6.

But the blogosphere would not replace architectural criticism. On the contrary, the rise of social media was at the expense of the blog. Engagement on Facebook, Twitter, or Tumblr took far less effort and anyone could participate. In the words of Throbbing Gristle, “Move a fin and the world turns / Sit in a chair and pictures change”—no navigating to separate sites, no logging in, just dashing off quick replies with the potential for wider visibility. It was the greatest thing since television. And if social platforms initially drove significant referral traffic to blogs, they gradually optimized to keep users within their own ecosystems, shadowbanning content with external links, leading to measurable declines in external referrals to blogs over time.

In retrospect, the first sign of stress in the blogosphere was the relentless rise of comment spam. What had begun as a trickle in the early 2000s became a devastating flood by 2010-2013, with automated bots filling blog comment sections with word salad along with links to questionable pharmaceuticals and gambling sites. Comment sections, once the vibrant heart of blogging communities where authors and readers engaged in substantive dialogue, became battlegrounds between legitimate conversation and algorithmic pollution. Blog owners found themselves spending hours each week moderating comments or implementing increasingly complex CAPTCHA and authentication systems that created friction for genuine commenters. Services like Akismet emerged to filter spam but required constant updating to keep pace with spammers’ evolving techniques and were annoying to use. Many influential bloggers eventually made the painful decision to disable comments entirely, severing a core interactive element that had distinguished blogs from traditional publishing. This degradation of community interaction further pushed conversations toward centralized social platforms where identity verification and spam filtering were built into the infrastructure, accelerating the migration of both content creators and their audiences away from the independent blogosphere.

A severe blow to the blogosphere came in 2013 when Google shuttered Google Reader, its popular RSS aggregator. RSS (Really Simple Syndication) had been the technological backbone allowing readers to efficiently follow multiple blogs without visiting each site individually. Google’s decision, citing declining usage, eliminated the most widely-used tool for RSS consumption overnight. Bloggers reported massive subscriber losses—Andrew Chen famously lost nearly 100,000 subscribers instantly. The infrastructure supporting independent blog discovery and consumption had been significantly weakened, pushing more creators and readers toward platform-centric ecosystems. The RSS icon, once ubiquitous across the web, began its slow fade from prominence.

As social media platforms captured ever-larger shares of attention, Medium, launched in 2012 by Evan Williams, represented a particularly insidious development—the co-founder of Blogger and Twitter—now building a platform that would ultimately absorb and commodify the independent publishing ecosystem his first creation had helped establish. Presenting itself as a savior of quality writing with its clean design and superior reading experience, Medium encouraged writers and entire publications to migrate their content, positioning itself as an alternative to maintaining independent blogs. But Medium was less a defender of blogging, more its corporate undertaker. After amassing sufficient content and attention, in 2017 Medium abruptly erected paywalls around content that had previously been freely accessible. Writers who had built audiences on the promise of open distribution suddenly found their work locked behind a $5/month subscription fee, with compensation tied to engagement metrics like “claps” and later reading time—a direct extension of the attention economy logic pioneered by social media platforms. This bait-and-switch tactic converted independent blogs into undifferentiated “content” feeding Medium’s subscription machine. Like Facebook and Twitter, Medium demonstrated that centralized platforms ultimately serve their own interests, not those of the creators who supply their content. The Medium experiment demonstrated the eagerness of Silicon Valley billionaires to capitalize subcultures without regard for the damage it would do. Rather than supporting a diverse ecosystem of voices with distinctive identities and direct audience relationships, Medium homogenized content under a single brand and aesthetic, reducing creators to interchangeable suppliers for its subscription business. Medium represented not evolution but extraction—a corporate attempt to capture the value of blogging while eliminating its independence and diversity.

Compounding all this was a political rift. By the time of the 2016 election, political polarization online had grown—not merely the right vs the left, but also an increasingly shrill progressive woke left that attacked liberals and centrists who were concerned, above all, that Trump not be elected. Social media, which of course played a huge role in this process, became the focus of attention and the vibrant conversations once hosted in the blogosphere degraded into bickering on sites, where interaction—however unpleasant—required less friction. The blogosphere splintered.

But even amidst this narrative of decline, blogging continued, only less so within architecture now. While microblogging and social feeds captured mass attention, a distinct cohort of interconnected blogs—largely British Marxists and lovers of post-punk music—maintained and deepened the intellectual promise of the medium through rigorous, extended explorations of complex topics and longer form pieces. Mark Fisher’s k-punk, launched in 2003 was what Simon Reynolds described as “the central hub of a ‘constellation of blogs’ in which popular culture, music, film, politics, and critical theory were discussed in tandem by journalists, academics, and colleagues.”7. This loose collective included writers like Reynolds himself, Benjamin Noys with his “No Useless Leniency” blog, Matthew Ingram who ran Woebot, aforementioned architecture blogger Owen Hatherley as well as others engaged in sustained cross-blog conversations. Blogging, for this group, became a central site for developing theoretical concepts. Noys notably coined the term “accelerationism” as an object of critique, while Fisher explored the possibilities of “acid communism”—demonstrating how blogging could sustain serious intellectual work outside academic institutions, which they increasingly saw as precarious. Fisher’s blog, Ryan Meehan wrote, was a “as a release valve from the pressures of academic writing. It became an impassioned and authoritative node in the hyperactive mid-aughts blogosphere—a network that, viewed from the social media quagmire of 2018, seems romantically free.”7. Fisher’s explorations of concepts like “capitalist realism,” “hauntology,” and the “slow cancellation of the future” began as blog posts before evolving into influential books published on the Zero Books imprint. His suicide in 2017 left a void in online Leftist thought, but cemented his legacy as one of the most important cultural theorists of his generation.

Returning to Scott Alexander, his Slate Star Codex (later a substack called Astral Codex Ten), written anonymously until his identity was controversially revealed by the New York Times, became a central hub for the rationalist community and attracted a wider readership interested in science, medicine, philosophy, politics, and futurism.The blog’s long-form essays delved into often controversial subjects, employing detailed arguments and statistical reasoning in ways that some saw as intellectually rigorous and others viewed as a gateway for legitimizing fringe or socially harmful ideas. Alexander’s practice of noting the “epistemic status” of his posts and the blog’s highly engaged comment sections fostered a culture of rigorous discussion that stood in stark contrast to social media’s superficiality. Similarly, Gwern.net, the website of pseudonymous independent researcher Gwern Branwen, represented another facet of the long-form resurgence. Known for exceptionally deep, data-rich research on topics ranging from AI and machine learning to psychology and self-experimentation, Gwern’s distinctive style features extensive annotations, footnotes, and sidenotes, reflecting a meticulous research process and a commitment to comprehensive evidence. The site’s unique design prioritizes content accessibility while deliberately rejecting web bloat. Gwern, incidentally, claims to live off of about $12,000 a year in order to devote himself full time to his passion of blogging. Longform podcasts like Dwarkesh (Patel’s), which features in-depth conversations with thinkers on AI and related matters have helped introduce the idea of long-form thought with broader audiences, undoing the dopamine-heavy obsession with the social media post. In providing platforms for extended, nuanced discussions, these podcasts serve as complementary mediums to long-form writing, allowing ideas to develop and cross-pollinate across formats.

Starting in 2017, Substack began providing a simple, integrated solution for such writers to launch newsletters and charge subscriptions. The platform experienced rapid growth, significantly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching over one million paying subscribers by late 2021. This model built on the same core values that drove blogging’s initial success—the desire for independent expression, direct audience connection, control over one’s platform, and space to explore ideas in depth.

For me personally, this renaissance of long-form, thoughtful content and the ease of uploading long form posts to WordPress and Substack presents a new opportunity. Though the architectural blogosphere I was once part of has largely disappeared, many of the problems I tried to address then have reemerged with even greater urgency—the interplay of space and technology, the role of technology in our lives, and society’s relationship to the built and natural environment, topics that demand the kind of sustained, thoughtful engagement that quick social media posts can’t provide. As yet, I don’t see a longer-form architecture community taking shape, and I wonder if I would be part of it—although John Hill’s A Daily Dose of Architecture, now A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books is on Substack as is Enrique Ramirez, with his “A New Literary History of Architecture.” For his part Adam Greenfield continues to write regularly at Patreon.

To conclude, let’s turn back to Scott Alexander’s musing about blogging’s “golden age” and his missed opportunity. While some early web pioneers like Marc Andreessen did indeed parlay their online presence into tremendous wealth and influence, others experienced a far different trajectory. Consider Robot Wisdom’s Jorn Barger, the coiner of “weblog.” Despite his pioneering status, Barger later found himself “homeless and broke” in San Francisco, “living on less than a dollar a day,” as reported by Wired magazine in 2005.8. The contrast is stark: the very man who named the medium couldn’t convert his innovation into financial stability, while others built empires. Given Andreessen’s recent behavior, it’s hardly a matter of mental stability; it’s the usual matter of getting lucky.

This disparity highlights how blogs were never primarily vehicles for wealth creation, institution-building, or an expected source of income for most of us. We did it for the hell of it. Alexander gets it all wrong by focusing on remuneration or professionalization. Blogging had—and once again has—a “golden age” precisely because we had no stakes in it. Blogs were significant not as business ventures but as independent voices outside traditional media channels. And that endures today. The true power of blogging is in ownership and control over one’s means of intellectual production. Those bloggers who sought professionalization or institutional validation—including in the academy— found themselves reabsorbed into existing systems. Pace Alexander, the most enduring legacy of blogging isn’t found in those who “graduated” to mainstream success but in those who maintained their independence, creating an alternative intellectual commons that operated according to different values than the market or the academy.

Blogging taught us that intellectual communities can form and flourish outside traditional institutions. My own journey from architecture blogging to explorations of native plant design and AI Art illustrates how these distributed conversations allow for intellectual evolution that might be constrained within more rigid disciplinary boundaries. The networked thinking that characterized the architectural blogosphere—its ability to connect seemingly disparate domains through hyperlinks and cross-disciplinary dialogue—offers a model for approaching the complex challenges we now face, from climate adaptation to reimagining collective space in a post-pandemic time.

As Mark Zuckerberg’s recent acknowledgment that “social media is over” suggests, the pendulum is swiftly swinging away from the algorithmic feeds and dopamine-driven engagement mechanisms that dominated the 2010s.9. Whether this is because individuals are occupying themselves in AI chatbots, just watching more streaming TV to escape, or are interested in longer form writing is, as yet unclear. Likely, it is all of these. Blogging, in some form, will endure for some time to come. Rather than a discrete historical moment, blogging is an enduring mode of independent intellectual engagement that persists despite evolving technological contexts. While architectural bloggers may have failed to transform architectural labor practices or fully democratize discourse, we nevertheless established alternative pathways for developing and sharing critical perspectives, if only temporarily. That achievement, modest though it may seem, represents a meaningful contribution to culture and maybe that’s enough.

1. Kazys Varnelis, proposal for sci * arc * wire, https://varnelis.net/sci-arc-wire/

2. Kazys Varnelis, Proposal for SCI * Arc * Wire, https://varnelis.net/sci-arc-wire/

3. Harvey Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place,” American Journal of Sociology, Volume 8, Number 2 (September 1976) , 309-332, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2777096.

4. Alexandra Lange, “Opinion, It’s easy to make fun of Bjarke Ingels on Instagram,” Dezeen, January 7, 2014. https://www.dezeen.com/2014/01/07/opinion-alexandra-lange-on-how-architects-should-use-social-media/

5. Amanda Lenhart, Kristen Purcell, Aaron Smith, and Kathryn Zickuhr, Social Media and Young Adults, Pew Research Center, Internet & American Life Project, February 3, 2010, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/02/03/social-media-and-young-adults-3/.

6. Davide Ponzini and Michele Nastasi, Starchitecture: Scenes, Actors, and Spectacles in Contemporary Cities (New York: Monacelli Press, 2016), 190-192.

7. Simon Reynolds, “Music & Theory,” Frieze, September 18, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20160304073857/http://blog.frieze.com/music_theory/.

8. Paul Boutin, “Robot Wisdom on the Street,” WIRED, July 1, 2005, https://www.wired.com/2005/07/robot-wisdom-on-the-street/.

9. Kyle Chayka, “Mark Zuckerberg Says Social Media is Over,” The New Yorker, April 23, 2025, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/mark-zuckerberg-says-social-media-is-over

Adam Greenfield reminds me that his blog was originally v-2.org, which he also points out meant that for a time his blog and Enrique's blog were called the same thing. v-2 was a fabulous blog and I am remiss in leaving it out. Adam didn't quite do long-form blogging back in the early 2000s, but he certainly did more than just post links.

I also didn't include Michael Doyle's Burnlab—http://theburnlab.blogspot.com—more design than architecture but still a good blog.