We had a beautiful day at Manitoga on Friday with the Native Plant Society of New Jersey (of which I am the President). There are few landscapes with this sort of power. I can’t think of a better site to go to within a short drive of New York City. It has as much impact as Fallingwater and is far better than Johnson’s Glass House, and yet it is hardly known among architects. We need to do better.

Next up is my promised third installment of the Skeptic’s Guide to AI and Art. I have been working outside a bit lately, as it is that time of year, but I need to get these done.

As always, you can read this on my blog, https://varnelis.net/the-florilegium/on-russel-wrights-manitoga-and-the-mid-century-american-landscape/ (the in-text references to the citations will only work as links there, or rather, they will send you there if you click on them). Please do reblog, share, and like this piece if you enjoyed it or learned something from it. As long as my site sees more traffic and my Substack sees more growth, I’m a happy writer.

I have driven NY-9D many times, crossing the Hudson at the Bear Mountain Bridge just south of West Point. When built in 1924, the two-lane span was the longest suspended bridge in the world, an elegant example of America’s infrastructural prowess. From there, it’s a scenic drive to Dia: Beacon with a stop at the quaint village of Cold Spring for lunch at Le Bouchon or Garrison’s Antipodean Books, a store specializing in antique volumes on exploration and geography. Along the way, I would see a sign announcing “Manitoga. The Russel Wright Design Center.” I didn’t recognize Wright’s name and was confused by the name Manitoga, which like the Canadian province, means “place of great spirit,” only in Algonquin, not Cree. Eventually, my curiosity led me to discover the midcentury modernist home built by industrial designer Russel Wright, sited dramatically in an abandoned quarry turned swimming basin, surrounded by a landscape of native plants.

I was surprised—and a bit suspicious—that, as a historian of architecture, I hadn’t heard of Manitoga. Perhaps it was derivative somehow, I thought, a second-tier project by an architect manqué? Still, having been surprised by the similarly obscure yet compelling James Rose Center in Ridgewood, New Jersey, I put it on my list of sites to visit. Early last December, I noticed a slot available on a tour and signed up.

In early winter, with the herbaceous perennials dormant, the site and house revealed their brilliance. Where, twenty years later, Robert Smithson could only dream of transforming an abandoned quarry into land art, Wright and his wife, Mary, also a designer, had chosen this anthropogenic disruption to build on. Mary died soon after they purchased the property, but Russel persevered and created a meditation on the relationship between human intervention and ecological processes. Instead of the reductive, sometimes kitsch, geometries of land art, Wright created something at once naturalistic and artificial. The exposed rock face, the diversion of a stream into a waterfall to feed the pond, and the strategic positioning of the house itself—all demonstrated an approach to site that differed fundamentally from contemporaneous modernist practices of the mid-century period.

The other day, I went back to Manitoga, this time with a group from the Native Plant Society of New Jersey, and with the site in the late spring glory of the northeastern forest. What had been a skeletal forest landscape, filled with shades of brown against dark evergreens, revealed a hillside full of ferns, understory plants, shrubs, and trees. If native plants are very much in the avant-garde of design today, Wright had embraced the aesthetic power of local plant communities in the 1950s. Even if he made his living as an industrial designer—most noted for his American Modern line of dishes—Wright eschewed the industrialized domestic landscape that was rising at the time and that has decimated biodiversity and created a visual blight—in Pat Sutton’s words, “neat as a pin, ugly as sin”—across the continent.

In trying to understand Manitoga along with Dragon Rock, the house and studio complex—named by Wright’s daughter because of the way the rock it sits upon resembles a dragon sipping from the quarry pond below—conventional art historical categories fail us. Wright’s work exists in a liminal zone between architecture, landscape, and what Smithson might have called “sites of entropy.” To truly grasp Manitoga requires a temporal awareness—seeing the landscape not as a static composition but as a dialectic between geological time and human manipulation, between the industrial violence of quarrying and Wright’s approach to it.

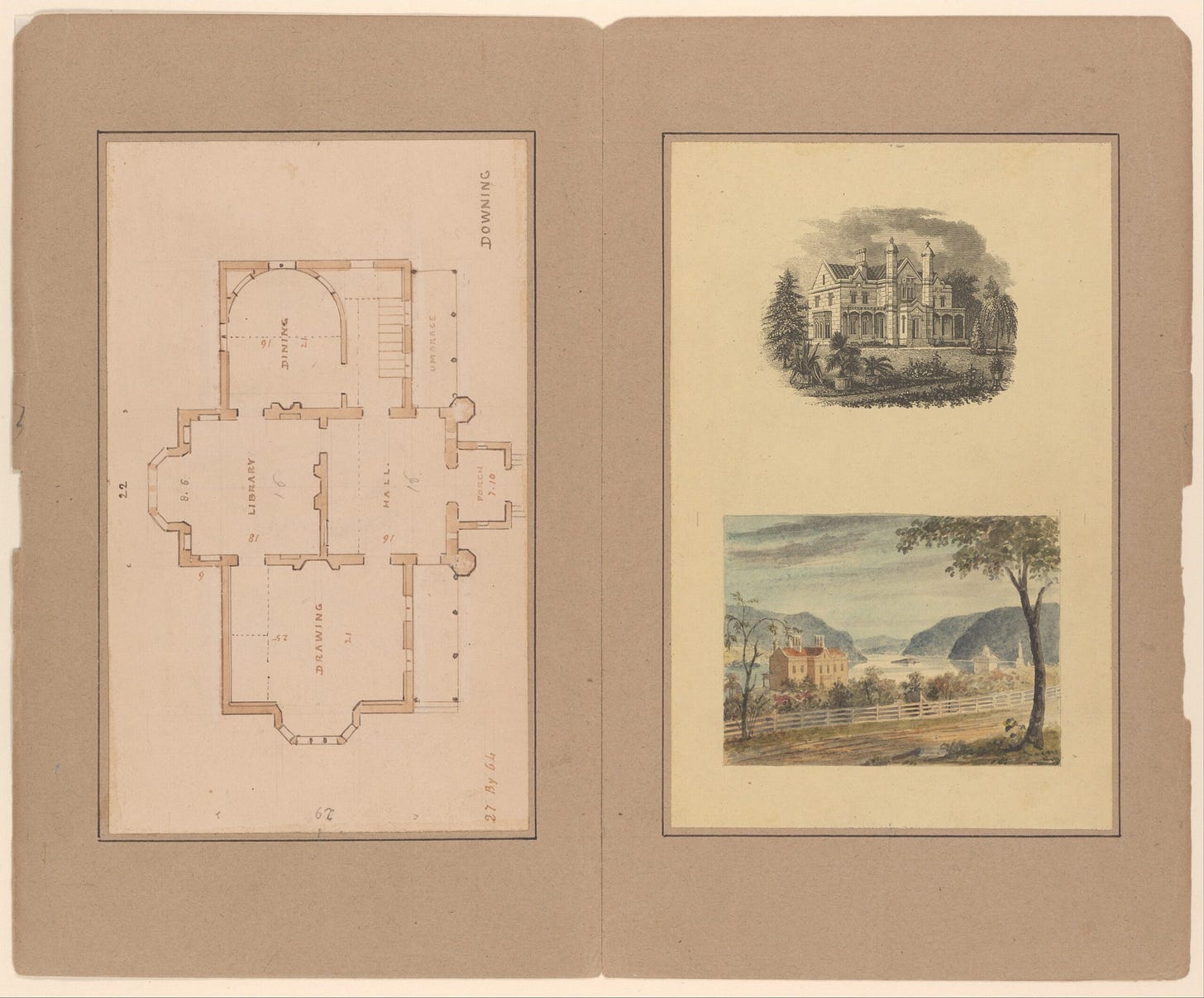

To come to an understanding of Wright at Manitoga, we need to first turn to its historical precedents in American landscape thinking and cross the Hudson to nearby Newburgh, where Andrew Jackson Downing practiced a century earlier. A nurseryman and writer as well as landscape and architecture theorist, Downing set out a framework for the American suburban domestic landscape and, in so doing, did more than anyone else to popularize the idea of suburban life as a desirable and morally superior mode of living.

The term “suburb” originates from the Latin suburbium, meaning “near the city.” Since antiquity, areas outside city walls have carried deeply ambivalent meanings. For the Romans, the inner suburbium housed those who couldn’t afford to live within the protected city center and housed activities deemed too noxious for urban life. Yet beyond this marginal zone, wealthy Romans established elegant villas in the near countryside as retreats from urban chaos. This contradictory legacy of suburbs as both zones of poverty and privilege persisted for centuries. In medieval and early modern Europe, the faubourgs of Paris and the suburbs of London acquired reputations as unruly, even dangerous spaces, yet simultaneously, elites from the Medici to the British aristocracy built country houses and villas on cities’ outskirts.

Downing’s vision emerged at a pivotal moment for the development of the suburb—America was rapidly industrializing, cities were growing denser, and a new middle class was seeking to define its identity. With the development of the railroad in the early 19th century, the term “suburb” became increasingly associated with desirable residential districts where the rising middle class could enjoy both proximity to urban opportunities and the tranquility of the countryside, using the railroad to bypass the slums on the outskirts of what would become known later as the “inner city.” Against this backdrop, Downing published his A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America (1841), followed by Cottage Residences (1842) and The Architecture of Country Houses (1850). In these works, Downing passionately advocated for the suburban villa—a home situated outside urban centers but still connected to civilization.

The suburban villa, in Downing’s conception, which he based on the ancient Roman villa suburbana, served multiple purposes beyond mere shelter. First, it provided a moral counterbalance to what he saw as the corrupting influence of city life. “The love of country is inseparably connected with the love of home,” he wrote in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, suggesting that domestic architecture and landscape could foster virtuous citizens.1 Second, it created a distinctly American aesthetic identity—rejecting the formality of European gardens in favor of the picturesque, with its emphasis on natural irregularity and scenic beauty. In the Treatise, Downing argued that “the formal and geometric style” of European gardens, with their “artificial and symmetrical forms” that imposed rigid order on the landscape were not as refined as the “modern or natural style” that imitated nature and worked with the inherent topography and vegetation of a site.2 Downing believed that landscape design should enhance rather than contradict the inherent character of a site. While not specifically advocating for native plants in the ecological sense we understand today, he nevertheless emphasized that gardens should harmonize with their surroundings and advocated the use of native trees in compositions.

Downing’s vision of the ideal American landscape was deeply tied to moral and physical health. He saw rural and suburban living as salubrious for body and soul, a preventative against the social and medical ills plaguing crowded cities. “Every external sign of beauty that awakens love in the young,” he wrote, strengthens attachment to home and “contributes largely to our stock of happiness, and to the elevation of the moral character.”3 This almost spiritual view of beauty as morality underpinned his work. Likewise, Downing championed the physical benefits of fresh air, sunlight, and space. He was remarkably progressive in advocating for proper ventilation, sewage disposal, and indoor plumbing, linking these directly to family health. His preference for spreading houses horizontally rather than vertically meant more windows for light and air, while his landscaping recommendations—planting trees and shrubs—improved the microclimate around homes.

Perhaps most revolutionary was Downing’s democratization of design through pattern books. Downing paired easy-to-copy architectural templates with comprehensive guides to tasteful living, covering everything from house plans to yard layouts, plant selection, interior furnishings, and heating systems. Written in accessible language for middle-class readers, Cottage Residences and The Architecture of Country Houses went through multiple editions and became style manuals for a burgeoning American middle class. By providing designs for different budgets—from elaborate villas to charming modest cottages—Downing reflected his belief that every American deserved a good home. The pattern books’ enormous popularity made picturesque suburban living seem both desirable and attainable, setting the template for American residential development for generations to come. The suburban villa, as envisioned by Downing, was not merely placed in the landscape but engaged with it through carefully designed relationships. Prospects and views were framed by strategic plantings. Approaches were choreographed to reveal the house gradually through winding paths. Ornamental grounds nearest the house gave way to more naturalistic arrangements at the property’s edges, creating a gradient of human intervention that mediated between domestic space and the wider landscape.

Downing’s premature death in 1852 at age 36—in a Hudson River steamboat accident—cut short his direct influence, but his ideas proliferated through his writings and through the work of his protégés, particularly Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, who would go on to design Central Park and establish landscape architecture as a profession in America.

Downing’s vision of domestic architecture and landscape found its most direct expression in the early planned suburbs that emerged shortly after his death. Llewellyn Park in New Jersey, established in 1853, was arguably America’s first planned suburb, explicitly following Downing’s model of picturesque scenery, winding roads, and villas set in park-like surroundings. Later developments like Riverside, Illinois, designed by Olmsted and Vaux in 1869, further refined these principles, creating carefully orchestrated landscapes where each house enjoyed naturalistic views and access to shared green spaces. These early suburbs were envisioned as preserving the moral and health benefits of rural life while maintaining access to urban amenities. Yet as suburbanization accelerated through the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Downing’s principles of site-specific design and harmonious integration with the landscape were gradually stripped away, while retaining his advocacy of a “finely kept lawn” adjacent to the house. By the 1950s, with developments like Levittown, the suburban ideal had been thoroughly industrialized and degraded. Mass production techniques enabled identical Cape Cod houses to be erected at the rate of 30 per day, while bulldozers scraped away existing vegetation to create blank slates for development. The contemplative relationship with nature that Downing prized gave way to standardized lawns maintained with chemical inputs, a homogeneous landscape as disconnected from its natural context as the urban tenements the suburbanites had fled. The industrialized suburb thus represented both the widespread popularization and profound reduction of Downing’s original vision.

As postwar suburbia expanded, a new residential phenomenon emerged, chronicled by August Spectorsky in his 1955 book The Exurbanites. Spectorsky identified a distinct social class choosing to live beyond the conventional suburbs, settling in rural areas within 50-100 miles of major cities. Unlike typical suburbanites in their Cape Cod houses, exurbanites were primarily “symbol manipulators”—advertising executives, writers, editors, artists, and other professionals whose work involved manipulating words, images, and ideas. Such taste leaders represented a cultural vanguard that, some 50 years later, Richard Florida would identify as “the Creative Class”—though with a crucial spatial inversion. Where Florida’s creatives would return to reinvigorate urban centers at the turn of the millennium, the postwar exurbanites fled them for pastoral settings. Mary and Russel Wright epitomized this exurban creative class. As industrial designers crafting modernist dinnerware for middle-class American homes, they shaped domestic taste—indeed, they published their Guide to Easier Living in 1950—while themselves seeking refuge from urban life in the dramatic landscape of Manitoga. Their choice to build not in suburbia but in an abandoned quarry 50 miles from Manhattan exemplified the exurbanite’s desire for a more authentic engagement with the landscape than cookie-cutter suburbs could provide, but did so in a unique, irreproducible manner.4

The relationship of exurbanites to both city and countryside was complex and often contradictory. While rejecting the conformity of suburbia, they nevertheless imported urban values, tastes, and amenities to their rural retreats. Commuting to Manhattan from genteel towns in Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, they sought what Spectorsky called “country living with city thinking.” Their gentrification of rural communities created tensions with locals and often involved the restoration of colonial-era homes or the construction of modernist houses in rustic settings. Their relationship with suburbanites was equally ambivalent—exurbanites generally viewed suburbs as bland, conformist environments lacking both urban sophistication and rural authenticity. Yet exurban communities like New Canaan, Connecticut, Princeton, New Jersey or New Hope, Pennsylvania functioned as exclusive enclaves, their real estate prices and cultural barriers effectively maintaining class separation from the mass suburbanization occurring closer to cities. The exurbanite phenomenon represented a new iteration of the villa tradition, where elites sought refuge from urban congestion while still maintaining the cultural and economic advantages of city life—yet another twist in the long historical dialectic between urban and rural ideals.

While documenting the exodus of creative professionals from urban centers, Spectorsky recognized the fundamental contradictions in their position. He observed how exurbanites often cultivated an image of rustic simplicity while simultaneously demanding sophisticated urban amenities—gourmet food shops, cultural venues, and high-end services. Their rural retreats became stages for performative rusticity that masked continued dependence on urban infrastructure and labor. Moreover, Spectorsky noted the paradoxical relationship between exurbanites and authentic rural life: they often romanticized local traditions and vernacular architecture while transforming communities in ways that priced out actual rural residents. Perhaps most damning was his recognition that exurbanites’ claim to have escaped urban social pressures was largely illusory—they had merely transported those same status competitions to new settings, creating enclaves that were desirable and exhaustingly social, much like life in the Hamptons today. Spectorsky chronicled the endless labor required to maintain this performative rurality—the ritual weekend mowing of vast lawns, the meticulous upkeep of swimming pools, the ceaseless battle against encroaching nature that contradicted the supposed embrace of country living. These maintenance rituals, often performed by hired help rather than the exurbanites themselves, revealed the fundamentally urban mindset that treated the landscape as something to be tamed and controlled rather than collaborated with or understood on its own terms.

Central to understanding both suburban and exurban development is Leo Marx’s concept of the “middle landscape,” which he explored in his 1964 study The Machine in the Garden. For Marx, the middle landscape represented an idealized space between wilderness and civilization—neither the untamed forest nor the crowded city, but a cultivated rural terrain that promised the best of both worlds. This concept had deep roots in American thought, from Jefferson’s agrarian ideal to Downing’s suburban villa. Marx pointed out that each generation reimagined this middle landscape according to its anxieties and aspirations. The postwar suburbs represented one manifestation of this dream—a domesticated nature of lawn and shade tree—while the exurban retreat offered a more rugged version, with its promise of authentic rural experience still within reach of urban commerce and culture. Wright’s Manitoga, poised between wilderness and civilization, exemplified this middle landscape ideal while complicating it. Rather than seeking pristine nature, Wright chose a site already marked by industrial use, suggesting that the true middle landscape of mid-century America existed not in an imagined pastoral ideal but in the creative reclamation of landscapes already transformed by human intervention.5

This tension between nature and technology that defined exurban life was precisely what Marx identified in his analysis of America’s long-standing ambivalence toward technology in the pastoral landscape. He cites Nathaniel Hawthorne’s account of sitting in the woods and being jolted by the whistle of a locomotive cutting through the tranquility. The exurbanites embodied this contradiction with particular intensity. The very machines they ostensibly fled—automobiles, commuter trains, telephones—were what made their rustic retreats viable. Their country homes often featured the latest modern amenities and architectural innovations, technological intrusions in supposedly natural settings. The exurban lifestyle depended upon a highly technologized infrastructure connecting rural outposts to urban centers, even as its participants romanticized their escape from urban mechanization.

As an exemplar of the exurbanite machine in the garden, there is no better—or more influential work—than Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut (1949). Deliberately situated a short drive after the last station on the Metro-North New Haven line, Johnson’s transparent pavilion represents a fundamentally different approach to the exurban condition. Where Wright embedded his home within the landscape, Johnson placed his atop it—a pristine box in a field of carefully manicured grass. The Glass House is a Corbusian “machine for living in,” depending entirely on mechanical air-conditioning for its habitability; without this technological intervention, the building would be uninhabitable in both summer and winter (in contrast, there is no air conditioning at Manitoga). Its relationship to the landscape is primarily visual rather than ecological or experiential. Johnson treated the surrounding woodland as scenery to be viewed through the house’s transparent walls, a picturesque backdrop rather than an environment to be engaged with. Over time, Johnson accumulated a collection of pavilions across the property—a brick library and guest house (which also contained the HVAC system for the transparent Glass House), painting gallery, sculpture gallery, second library and workspace, and a series of follies—creating what amounted to a modern day 18th century landscape or, less charitably, as a personal architectural theme park. Johnson’s main engagement with the landscape was a relentless excision of trees and understory plants from the formerly wooded site. For Johnson, the landscape was more like something to be viewed through the windows, as if on a television screen. This approach to the landscape as something to be viewed in a detached way, rather than engaged with as a living system, reveals the limitations of this strain of high modernism’s engagement with nature. Here, landscape becomes passive, meticulously composed yet fundamentally decorative and subordinate to the house—a stark contrast to the dynamic, immersive environment Wright created at Manitoga.

Johnson’s pristine modernism stands in stark contrast to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (1939), completed a decade earlier in rural Pennsylvania. Where Johnson placed his glass box atop the landscape as a pure geometric form, Wright anchored his structure into the site, dramatically cantilevering concrete terraces over a waterfall. The rivalry between these architects reflected fundamental disagreements about architecture’s relationship to nature and order. Johnson famously dismissed Wright as “the greatest architect of the nineteenth century,” while meeting Johnson at Yale, Wright said “Why, little Phil, I thought you were dead! Are you still putting up all those little houses and leaving them out in the rain?” Fallingwater neither dominates the landscape nor merely frames it; instead, the house emerges from it, with local sandstone walls rising from the same rock on which the house sits, stream water circulating through the house, and forest views penetrating every room.

This integration of architecture and landscape had roots in Wright’s Prairie Style as well as in a dialogue with his contemporary, landscape architect Jens Jensen. A pioneering Danish-American designer, Jensen advocated for what he called the “native landscape,” using indigenous plants of the Midwest to create naturalistic compositions that expressed regional identity and ecological relationships. His influence on Wright was profound, encouraging an architecture responsive to the horizontal expanses of the prairie landscape and the use of local materials, and, in turn, Wilhelm Miller would dub Jensen’s approach “the prairie style” of landscape gardening, appropriating Wright’s term for his own work architectural style of low-slung horizontal lines, deep eaves, and integration with the landscape. As Russel Wright would later do at Manitoga, Jensen generally rejected exotic imports, preferring native plants arranged according to their natural associations—what we now recognize as plant communities.

Fallingwater, though built in a wooded Appalachian setting rather than the Midwest prairie, carries forward this commitment to site specificity while also incorporating Wright’s growing fascination with Japanese aesthetics. Wright had been captivated by Japanese design since first seeing the Ho-o-den pavilion at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. His subsequent travels to Japan in 1913 and his work on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1916-1922) profoundly influenced his architectural thinking. The integration of indoor and outdoor spaces, the emphasis on horizontal planes, and the careful framing of natural views all reflect principles found in traditional Japanese architecture. Yet Wright created work that inspired by, not derivative of Japanese aesthetics. Beyond its cultural influences, Fallingwater also embodied a distinctly American social pattern—it served as an exurban retreat for the wealthy Kaufmann family, department store magnates from Pittsburgh seeking respite from urban life. In this sense, it reimagined the traditional country house for the industrial age, situated within driving distance of the city yet immersed in a seemingly pristine natural setting.

Russel and Frank Lloyd Wright knew each other and Russel sought out the elder architect, visting him in 1952, but despite its brilliant integration with its setting and Fallingwater represents a different approach than Russel Wright would take at Manitoga. Like the Glass House, Wright’s building still imposes a powerful human-designed geometry onto a pristine natural site, privileging formal drama over ecological processes. The massive concrete cantilevers—technological feats requiring extensive reinforcement—dramatically transform a previously untouched landscape. Fallingwater celebrates the creative genius of the individual architect rather than the collaborative dialogue with natural systems that Dragon Rock would embody. Where Fallingwater commands attention through bold formal gestures in a pristine setting, Manitoga would pursue a quieter, more reciprocal relationship with a damaged landscape. Both engage with their sites intimately, but to radically different ends: Fallingwater as an assertive architectural statement within nature, Manitoga as a healing conversation between human intervention and ecological regeneration.

Another, kindred approach—if in a different register—can be found in Charles and Ray Eames’s own home in Pacific Palisades (1949). Like the Wrights, the Eameses were industrial designers who shaped postwar American domestic life through their furniture and exhibitions. Their house, like Manitoga, represented a marriage of modernist principles with a respect for site conditions. The Eames House preserved a row of existing eucalyptus trees—admittedly not only non-native but quite invasive—and cut into the hillside behind them rather than dominating the site. The steel-framed structure functioned as a framework for living rather than a prescriptive environment, filled with collected objects, textiles, and plants that created a vibrant, evolving interior landscape. Like both Wrights (Frank Lloyd and Russel), the Eameses were deeply influenced by Japanese aesthetics—evident in their appreciation for natural materials, modular design principles, and the poetic juxtaposition of objects in space.

Unlike Johnson, who saw himself as a design aristocrat, the Wrights and the Eameses participated in a broader postwar project to reimagine everyday—or at least upper middle-class—American domesticity through a synthesis of modern design and casual living. The Eames House was part of Arts & Architecture magazine’s influential Case Study House program, which commissioned architects to design prototype homes for the postwar era. These houses were explicitly marketed to Southern California’s technical-professional class—aerospace engineers, defense industry scientists, and Hollywood creatives—who embraced technology while seeking a more relaxed lifestyle. Similarly, the Wrights’ 1950 book Guide to Easier Living promoted an informal, practical approach to home design that freed homeowners (particularly women) from burdensome domestic conventions.6 Tragically, Mary Wright passed away after a year long battle with breast cancer in 1952, shortly after the couple purchased the Manitoga property. Her absence makes direct comparison with the collaborative Eames practice somewhat poignant—Charles and Ray worked as equals throughout their lives, while Russel had to carry forward their joint ambitions alone.

A telling difference between Johnson and the Eames/Russel Wright approaches emerges in their attitude toward time and completion. The Eameses famously documented their house in the short film “House: After Five Years of Living” (1955), suggesting that a home was not truly finished until it had been lived in and layered with personal collections and artifacts. This philosophy of ongoing adaptation contrasts sharply with Johnson’s more static, sculptural approach to architecture. Russel Wright’s decades-long development of Manitoga—constantly adjusting paths, plantings, and water features and tinkering with the house—likewise embraced design as a continuing dialogue with place rather than a finite architectural statement. Both the Eames House and Manitoga were conceived not as pristine aesthetic objects but as evolving frameworks for living, where the machine was not simply placed in the garden but integrated the messy, accumulative nature of human habitation and, in the case of Manitoga, ecological processes.

In his account, Russel and Mary Wright took trains to Garrison in search of a suitable site with views of the Hudson (Russel’s desire) and a place to swim (which Mary wanted) and hiked around until they found the abandoned quarry, with its gouged granite walls, the forest stripped for industrial exploitation.7 After Mary’s untimely death in 1952, Russel continued their vision alone, and across two decades created an alternative synthesis that inverted the prevailing architectural paradigms of his time.

Where Johnson, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Eameses all reshaped relatively pristine sites for their architectural statements, Wright embraced disturbance and damage as design opportunities. He approached the scarred landscape not as something to be concealed or erased, but as raw material for a new kind of environmental art. Wright terraced quarry spoil piles into cascading moss gardens, repurposed industrial rubble for Dragon Rock’s walls, and ingeniously redirected natural run-off to create a pond whose high, dark water mirrors the cliff face. This practice of healing-as-design anticipated by decades our contemporary fascination with adaptive reuse and post-industrial landscapes. Wright understood that in a world increasingly marked by human intervention, true environmental stewardship must include the reclamation of damaged places, not just the preservation of pristine ones.

Wright’s design approach was also deeply informed by Japanese principles—notably, he had gone to Japan for the US State Department to help find Japanese goods to import. Having seen an article about young architect David Levitt’s New York apartment, which was informed by Levitt’s own time working in Japan, he hired Levitt and his firm Leavitt, Henshell and Kawai to design the house.8 Yet he avoided the superficial, appropriation of Asian motifs that characterized—and still characterize—so much of American borrowing from Japanese design (I discuss this at length in my previous essay, The Phantasmagoria of the Landscape: Japanese Gardens in America). Long fascinated by Japanese craft and garden traditions, Wright employed asymmetry, borrowed scenery (shakkei), and choreographed movement along sequential paths that reveal and conceal views in carefully orchestrated sequences. This Japanese influence paralleled the Eameses’ similar fascination—they too absorbed Japanese principles of modularity, adaptability, and the celebration of everyday objects. Both Wright and the Eameses understood that Japanese design offered not just visual motifs but a profound philosophy about the relationship between space, object, and human experience. When it came to the garden at Manitoga, Wright also largely rejected the American habit of importing cherries and maples to create simulacra of Oriental gardens. Instead, his plant palette is almost entirely Hudson Valley native—hemlock, white pine, mountain laurel, maidenhair fern—creating a landscape that feels simultaneously Japanese in its spatial principles and deeply rooted in its local ecology. His extensive cultivation of moss he found on the site recalls the spirit of Kyoto’s Saihō-ji temple, without feeling derivative. His approach invites comparison with the Sakuteiki’s ancient admonition to “follow the request of the stone,” suggesting that Wright had grasped the spiritual essence of Japanese garden design rather than merely its formal vocabulary.

Perhaps most revolutionary was Wright’s conception of architecture not as a machine for living but as a metabolic membrane between human and natural worlds. Dragon Rock features tree trunks that pierce roof openings, bringing living matter directly into the home. Glass walls slide away, erasing the boundary between interior and exterior. Summer breezes replace Johnson’s air conditioning, as the house was designed to be naturally ventilated through strategic openings that capture prevailing winds. The house is unquestionably a human intervention, but it is neither a technological machine indifferent to its setting nor a scenic prop framing picturesque views, but a porous threshold mediating light, moisture, temperature, and seasonal change.

As a designer of industrially produced objects, Wright had long been concerned with the role of the individual in the mass society. In the opening to their Guide to Easier Living, Russell and Mary wrote: “In this increasingly mechanized civilization, our homes are the one remaining place for personal expression, the place where we could really be ourselves. But in actuality they are more often than not undistinguished and without individuality, monuments to meaningless conformity.”9 He addressed how this mindset affected his thinking about his house in a 1961 lecture stating, “Dragon Rock, the house in Garrison, must not be thought of as a prototype—it is an exaggerated demonstration of how individual a house can be.”10

While Wright shares with the Eameses a deep commitment to integrating modern life with natural surroundings, their approaches differ in significant ways. The Eames House embraces industrial materials and prefabrication as expressions of postwar technological optimism; its steel frame and colorful, painted panels celebrate the machine aesthetic even as they are set off by the row of eucalyptus. The myriad objects that the Eames’s collected on their travels are the chief natural materials in the house while Wright, by contrast, purposefully incorporates both natural materials and technological ones in the house itself.

In doing the designing, I considered various types of materials. Here are some of the natural materials which are used in the house: lumber, in various conditions, sanded and finished, weathered, rough-cut, or lumber just with the bark removed. Leather, fur, stone, birch-bark, copper. This collection shows the extremely rich-textured natural materials, I think that they give on an impression that is too richa nd too resltless. Here are a few of the man-made materials used in the house: fiberglass, formica, foam rubber, metal foil, styrofoam.

These man-made materials are exactly the opposite of the natural ones. The natural materials are amorphic in shape and organic in texture. The machine-made ones have the repetition of the manufacturer: they are sleek, smooth. “what I have done is combine the two. The combination of the natural with the machine-made makes one type of material compliment or enhance the other.11

Where the Eameses created a container for their vast collection of objects—a cabinet of curiosities that reflected their omnivorous cultural appetite—Wright cultivated absence and restraint, allowing the surrounding landscape to become the primary visual experience. Yet both rejected the sterile monumentality of high modernism, so beloved by Johnson, in favor of homes that evolved organically through use and time.

Wright’s most profound contribution may be his counter-exurban ethic. Where Spectorsky’s typical exurbanite curated nature as a status accessory—a manicured backdrop for cocktail parties or weekend recreation—Wright practiced a deeper engagement that relinquished pictorial control and embraced natural processes. At Manitoga, fallen branches are left to rot, leaves to accumulate, rock surfaces to weather to lichened silver. Nature is not frozen in an idealized state but allowed to evolve, die, decompose, and regenerate. Gardening becomes an ongoing collaboration of curation with ecological systems rather than a weekly maintenance spectacle performed by hired help with gas-powered devices. This approach prefigured the current avant-garde in landscape gardening, challenging the prevailing consumerist relationship to landscape that characterized much of exurban (and suburban) development since World War II. Against Johnson’s machine-in-the-garden it dissolves the machine into the garden while acknowledging the damage we have wrought, transforming industrial ruin into ecological theater where human intervention becomes not an imposition but a catalyst for new kinds of natural beauty. Against the typical exurban approach to landscape as status symbol, it proposes a model of stewardship based on reciprocity rather than consumption.

Wright’s commitment to native plants at Manitoga represents one of his most visionary and ecologically significant contributions. While modern ecological restoration was still in its infancy, Wright intuitively understood the importance of working with indigenous plant communities rather than merely imposing exotic ornamentals. These weren’t arranged in conventional garden beds but placed according to their natural associations—ferns and mosses in damp ravines, blueberry shrubs along woodland edges, wildflowers in seasonal progressions of bloom. Wright didn’t merely preserve what was already there—the site had been ecologically devastated by quarrying—but actively reintroduced native species appropriate to the regional ecology. This approach dramatically differed from conventional landscaping of the era, which favored either exotic specimen plantings or formal arrangements. Unlike the typical suburban yard with its uniform lawn punctuated by non-native foundation shrubs, Manitoga’s landscape embraced seasonal change, ecological succession, and the subtle beauty of native plant communities. Wright recognized that the Hudson Valley’s indigenous flora possessed as much aesthetic power as any exotic import, while providing essential habitat for wildlife and requiring far less intensive maintenance. By rejecting the standard practice of clearing, grading, and replanting with exotic specimens, Wright demonstrated a profound respect for place and process that anticipated today’s native plant movement by half a century. His garden wasn’t a static composition but a dynamic system, incorporating natural cycles of growth, decay, and regeneration rather than attempting to freeze the landscape in a permanent state of visual perfection.

During our discussion, landscape curator Emily Phillips, who has done such fabulous work on the site, pointed out that Edith A. Roberts, who had been a professor of botany at nearby Vassar College, had written a book on native plants called American Plants for American Gardens (1929). One can only wonder if Wright could have missed that connection. That said, the only caution with regard to Wright at Manitoga is that while he did not plant Japanese red maple or cherry trees as specimens to invoke “Japaneseness,” but rather used Japanese principles of design, choosing to accentuate existing forms among his trees and shrubs that he found compelling and going so far as to hire he did plant a small number of plants we now consider invasive and inappropriate. Generally, however, these were not specimens but rather what he might have called “ditch plants” or weeds. Carolyn Levy Franklin, one of the founders of the Andropogon landscape design firm—a storied pioneer in restoration—listed “Queen Anne’s lace, daisies, chicory, goldenrod, and coltsfoot” as examples in her extensive “Design and Management” guide to Manitoga wrote, adding that “These largely European herbaceous plants speak whimsically of the intervention of man in the landscape, as does the iron ring still implanted in the largest boulder—a relic from the days of quarrying. These largely European herbaceous plants speak whimsically of the intervention of man in the landscape, as does the iron ring still implanted in the largest boulder—a relic from the days of quarrying.”12 Although this approach, similar to that of Claudia West and Thomas Rainer’s “post-wild” strategy, would be dangerous and inappropriate in any site without professional, on-site staff, at Manitoga, the landscape team works to keep invasives to a minimum and has removed the most dangerous non-natives.

But overall, Manitoga offers a stark alternative to the geometric domination that still characterizes much landscape design. By attending to the spirit rather than the specimens of Japanese tradition, honoring native plant communities without parochialism or sentimentality, and accepting entropy as co-author rather than enemy, Manitoga presents a model for post-carbon, post-industrial dwelling—one in which architecture and terrain enter a long, reciprocal conversation rather than a short and violent encounter. This is not just landscape design, it is a model for a reenvisioned land art. In an era of climate crisis and biodiversity collapse, Wright’s vision of design as a healing practice that enhances rather than replaces ecological function feels more urgent than ever.

I would like to thank Emily Phillips, Kathryn Tam, and Richard Rockwell at the Russell Wright Foundation for leading our tour as well as Sarah Pansy of the Foundation and Kim Correro, Head of Programs at NPSNJ for organizing our excursion.

1. Andrew Jackson Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), iii, https://archive.org/details/treatiseontheory41down.

2. Downing, Treatise, 10-15.

3. Alexander Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1852), vi, https://archive.org/details/architectureofco00down/

4. Auguste Comte Spectorsky, The Exurbanites (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1955). Mary Wright and Russel Wright, Guide to Easier Living (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950).

5. Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964).

6. Mary Wright and Russel Wright, Guide to Easier Living (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950). https://archive.org/details/mary-and-russel-wrights-guide-to-easier-living

7. Russel Wright, “Russel Wright Lecture” in Jennifer Golub, ed. Russel and Mary Wright: Dragon Rock at Manitoga (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2021), 137-150.

8. David L. Leavitt, “The Origin of Dragon Rock,” Manitoga / The Russel Wright Design Center, https://www.visitmanitoga.org/essay-david-leavitt. For the New York Times article, see here Betty Pepis, “Japanese Serenity in a Manhattan Apartment; Orient Visit Sparks Redecoration of Home,” The New York Times, November 28, 1955, https://www.nytimes.com/1955/11/28/archives/japanese-serenity-in-a-manhattan-apartment-orient-visit-sparks.html.

9. Wright and Wright, Guide to Easier Living, 1.

10. Wright, “Russel Wright Lecture,” 137.

11. Wright, “Russel Wright Lecture,” 139

12. Carol Levy Franklin, Design and Management Guide for Manitoga: A Preserve of The Nature Conservancy, Garrison, New York (December 1982), prepared under Grant #11-4213-264 from the National Endowment for the Arts, Design Arts Program, https://www.visitmanitoga.org/design-management-guide