This is a bit more theoretical, quite a contrast to the last piece on skunk cabbage, but that’s the nature of the Interminable Flights Substack and indeed of the mindset of a synthesist: bit of a cabinet of curiosities.

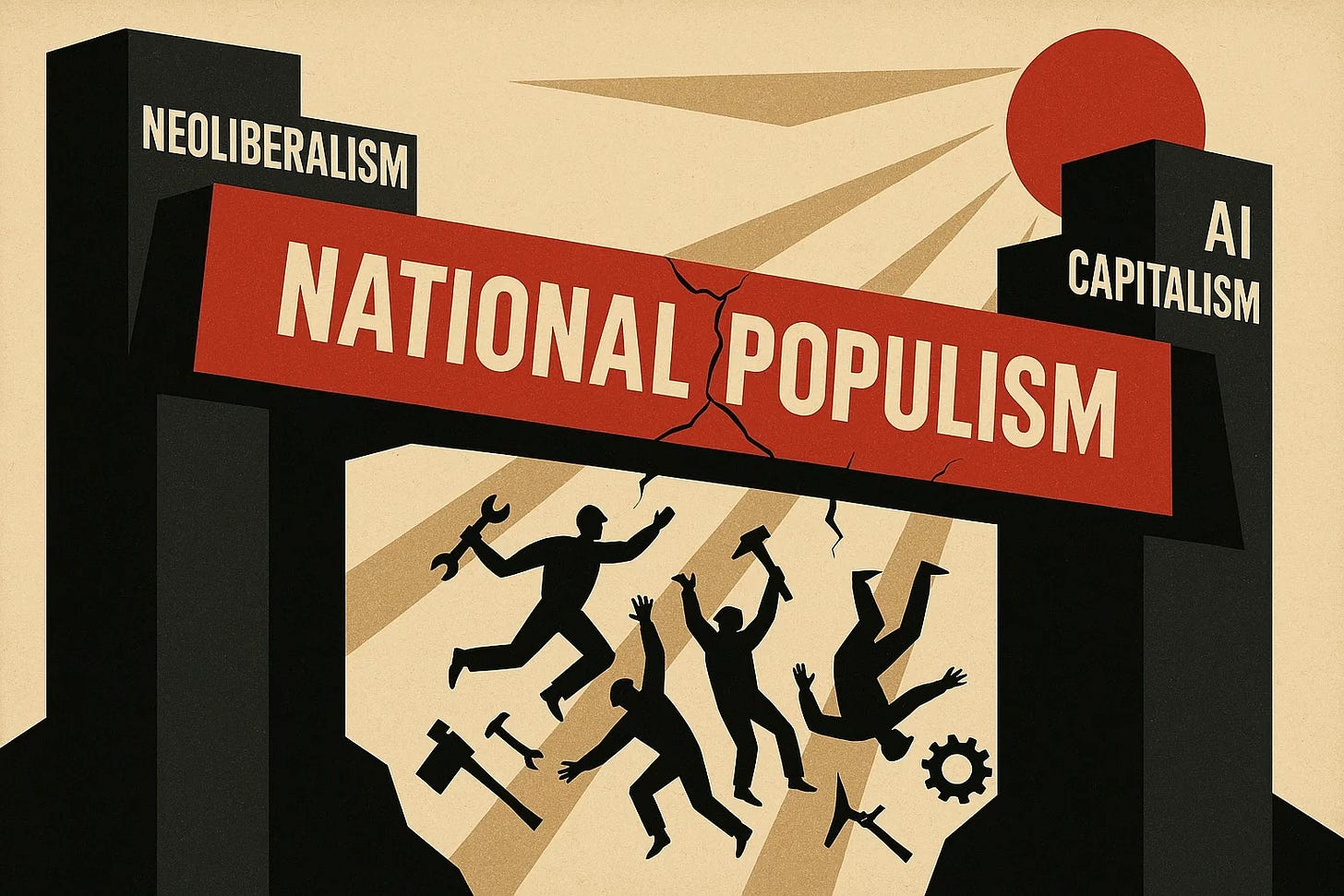

Like many of you, I have been trying to make sense of the current political landscape in the US and elsewhere, but I have also have been working on updating my argument about Network Culture—a historical phase marked by digital networks and neoliberal economics—and exploring what comes next. The result is this new essay on National Populism, not merely as a political ideology but as a transitional form emerging during capitalism’s shift from neoliberalism to what I term “AI Capitalism,” in which artificial intelligence becomes central to economic activity. There aren’t references to art or architecture here—those will come later, once the cultural outlines of this moment become clearer.

My interest is in how National Populism serves as a stopgap amid profound economic transformation. Populist movements promise restored manufacturing, national sovereignty, and cultural revival, yet in practice their policies accelerate financialization and deregulation, ironically undermining these promises. The tragic irony is that the National Populist base itself suffers the most: their legitimate grievances about economic dispossession are channeled into a movement that intensifies rather than resolves their obsolescence.

I don’t have the time to figure out how to make the footnote links work on Substack so they link to my site. You can just scroll to the bottom of this piece if you want to read them.

As always, this work can also be found at https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/national-populism-as-a-transitional-mode-of-regulation/

For two decades, beginning at SCI_Arc and concluding at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation, and Planning, I taught a course called Network City. In that course, I employed the Regulation School’s framework of regimes of accumulation and modes of regulation to explore urban transformations accompanying the shift from Fordist mass production to post-Fordist flexible specialization. Through case studies such as the Park Avenue business district in 1950s New York, the shopping mall, the suburban office park, the so-called “creative city” movement, the Bilbao-effect, and the dot.com workplace we examined the interplay of economic structures, governance models, and spatial organization underlying contemporary networked urbanism. Since the 2024 election, several former students and colleagues have reached out, expressing frustration as they try to make sense of the changes underway today. This prompted me to reflect at length on the phenomenon of Trumpism—better known as MAGA, or more appropriately, National Populism.

Although my focus here is on the American manifestation of National Populism, which makes global news daily, this phenomenon extends beyond the United States, appearing in countries like Brazil, Argentina, Hungary, and India. Between 1990 and 2018, the number of populist leaders in power worldwide jumped fivefold (from 4 to 20), reflecting a global shift in political dynamics.1 Globally, 2024 was a bad year for most incumbents, but right-wing populism maintained its strength overall, gaining ground in countries like Germany and France. No longer an outlier, such parties are now firmly part of the political landscape.2 While China’s authoritarian populism differs substantially in structure and goals, it too reflects the global turn toward reactionary politics, with the Chinese Communist Party making more appeals to national identity and cultural restoration similar to other populist movements. Unlike my Network City project, I am not going to use this essay to write about the architectural and urbanistic manifestations. There is, as yet, no clarity to these—and I am still working on interpreting its cultural logic—but the general contours of ongoing societal shifts have become clearer. I should add that while I am increasingly wary of academic narratives in which capitalism is presented as the chief animating force of history, it only makes sense to talk about capitalism when we are talking about socioeconomic developments.

Contemporary progressivism struggled to offer a compelling vision capable of addressing the economic and social anxieties fueling populist resentment. Indeed, its efforts seem to have backfired, with the progressive politics of the Biden administration—elected to be a moderate caretaker administration—driving the Democrats further and further away from their core constituency while alienating many among the minorities Democrats sought to court with their vision of identity politics. This ideological failure created an opening that National Populism eagerly exploited.

While analyses of National Populism in America commonly emphasize its political dimensions in America—nationalism, isolationism, and identity politics—its economic role as a mode of regulation has generally been overlooked. I argue that National Populism should be understood not merely as a political ideology but as a transitional regulatory mechanism emerging during capitalism’s shift from neoliberalism toward a new economic order dominated by artificial intelligence—what I term “AI Capitalism.” Even if this transformation remains largely unconscious—it is hard to believe that Trump himself has any grasp of its full dimensions and certainly his rank-and-file supporters do not—and poorly theorized, it is well underway and will inevitably provoke profound conflict in the years ahead, not just between Republicans and Democrats, but within the GOP as well.

Before proceeding further, I should clarify what I mean by regimes of accumulation and modes of regulation, two concepts central to the French Regulation School’s approach to political economy, made popular in the United States by David Harvey’s Condition of Postmodernity.3 A regime of accumulation refers to the way capitalism organizes production and consumption to enable profit and growth over an extended period. It encompasses specific technologies, labor processes, consumption patterns, and capital-labor relations that allow value creation and capture. The Fordist regime of accumulation, for example, featured mass production, unionized labor, rising wages, and mass consumption, while the flexible accumulation regime that followed emphasized global supply chains, precarious employment, and debt-fueled consumption.

A mode of regulation, by contrast, comprises the institutional forms, networks, and norms that stabilize a given regime of accumulation. This includes everything from formal laws and financial systems to cultural practices and modes of state intervention. The Keynesian welfare state was the mode of regulation that supported Fordism, while neoliberalism and the attendant monetary policy ultimately emerged as the regulatory framework for flexible accumulation. As Harvey concludes, broader cultural logics correspond to these modes, characterized by modernism and postmodernism respectively. In each case, the mode of regulation attempts to temporarily manage capitalism’s inherent contradictions and crisis tendencies through specific institutional arrangements.

In “Almost Anything,” my essay on the work of architect Kevin Roche that modernism had three main cultural phases—its nascent pre-World War 2 state, high modernism of the postwar era, and the late modernism of the 1960s and 1970s when the ideology was exhausted. In turn, postmodernism was succeeded by network culture, a concept I explored as neoliberalism’s final cultural and economic logic, a period characterized by decentralized networks, fragmented identities, and pervasive commodification of digital interaction (it is arguable that a pop art-rock culture preceded postmodernism as a logic of flexible accumulation even as it overlapped with late modernism.4 However, network culture represented neoliberalism’s final cultural phase, inadvertently amplifying its inherent contradictions rather than stabilizing it. Through the deregulation and amplification of information flows, fragmentation of the polity into “networked publics” and the collapse of stable identities, network culture eroded political consensus, generating fertile ground for populist narratives.

Like network culture, National Populism is transitional in nature. Modes of regulation don’t last forever. They emerge in response to the contradictions of prior systems, stabilize a regime of accumulation, and eventually break down. Its primary features—economic nationalism, identity politics, and anti-intellectualism—suggest a complex effort to manage the transition between economic regimes, even if it seems unlikely that its proponents have any idea of (or plan for) what it might evolve into.

Political scientist Cas Mudde defines populism as a “thin-centered ideology” that splits society into two antagonistic camps: “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite.” Populists claim to uniquely represent the true people’s will against self-serving establishment elites. Importantly, populism is “thin” because it does not on its own offer a detailed economic or policy program – it attaches to a “host” ideology. In the case of National Populism, the host ideology is nationalism or nativism. National-populist movements thus frame the elite as globalist traitors and champion the people as the native citizens of the nation-state, often scapegoating immigrants or foreign influences for domestic woes.5

According to John Judis, populism is fundamentally driven by questions of economic distribution—who gets what— even if the anger often expresses itself in cultural terms. In Western nations, decades of neoliberal globalization allowed corporations to outsource jobs and chase lower wages abroad, while domestic workers felt left behind. By the 2010s, this translated into voter frustration with mainstream parties and openness to outsiders promising to upend the status quo. Specifically, Judis underscores that both left and right populists (from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump) challenged at least one pillar of post-1970s neoliberalism: the free movement of corporations and capital across borders. In practice, right-wing national populists tend to combine cultural backlash with economic nationalism—opposing free trade agreements, advocating tariffs or protection for local industry, and pledging to bring back manufacturing jobs. They often pair this with welfare chauvinism (maintaining or expanding welfare benefits for native citizens only) and skepticism of immigration. This agenda is offered as a corrective to the dislocations and inequities that globalization (and now technological change) have created.6

At the same time, many scholars emphasize that National Populism is a symptom of deeper structural changes. Economic insecurity, regional inequalities, and the decline of traditional industries set the stage for populist resentment. Cas Mudde and others observe that while populists loudly critique elites, most still operate within a capitalist market framework, often proposing few concrete changes to the economic system. In fact, once in power, populist leaders frequently implement a mix of contradictory policies—tax cuts and deregulation benefiting businesses and investors, alongside trade protection or fiscal stimulus to appease working-class supporters. This inconsistency hints that National Populism may be less an enduring model and more an interim balancing act.

The current wave of technological innovation—centered on artificial intelligence, automation, and data—is ushering in what I term “AI Capitalism.” This is a rather natural term, but it seems that it was introduced by Nick Dyer-Witheford, Atle Mikkola Kjøsen, and James Steinhoff in their book Inhuman Power: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Capitalism as “actually-existing AI Capitalism.” Of course, a book written over six years ago is ancient history in AI terms and their reference is to the earlier use of narrow AI or machine learning algorithms. Just as “actually-existing socialism” was a reference to the deeply flawed nature of Communist regimes, the authors use the phrase to refer to the difference between machine learning and the generalist AI of the sort that ChatGPT and other LLMs have offered in the years since. Still, the authors get a lot right, emphasizing how major tech corporations “see the cognitive and biological limits of the human as a barrier to accumulation” and aim to bypass those constraints using machine learning, automation, and predictive analytics. In their framework, AI is not just another industry but a means of cognition—an infrastructure that is fast becoming a general condition of capitalist production, much like electricity or global supply chains in earlier eras. They also share my view that AI Capitalism will have a profound impact on labor, making vast numbers of workers obsolete, critiquing both right-wing and left-wing perspectives that downplay the threat of automation, arguing instead that AI-driven job displacement will be deep and systemic. They document how AI does not merely assist workers but actively records human labor in order to replace it—Amazon’s robotic warehouses, AI-driven call center automation, and algorithmic surveillance are all part of this trend. Indeed, they also understand that the result of this automation will be an ever-growing surplus population that capital no longer requires, making permanent unemployment and precarity central features of AI Capitalism. More than that, they propose that even the narrow concept of machine learning, makes AI an essential form of infrastructure, such as water or energy:

“If AI becomes the new electricity, it will be applied not only as an intensified form of workplace automation, but also as a basis for a deep and extensive infrastructural reorganization of the capitalist economy as such. This ubiquity of AI would mean that it would not take the form of particular tools deployed by individual capitalists, but, like electricity and telecommunications are today, it would be infrastructure—the means of cognition—presupposed by the production processes of any and all capitalist enterprises. As such, it would be a general condition of production.”7

In both their analysis and mine, “AI as infrastructure” will be controlled by oligopolistic firms—tech giants who are investing billions to advance AI and capture its benefits. My own view of AI Capitalism—which also draws upon general consensus in business and tech journalism and commentary on AI—is that it represents an emergent stage of capitalism in which data and AI algorithms become core components of economic production, augmenting and replacing intellectual and creative laborers the way that factory labor was replaced under post-Fordism. While new jobs will also be created (and optimistic scenarios suggest overall employment can remain stable in the long run), the transition will be tumultuous. Entire sectors – from manufacturing to clerical office work – are being reshaped.

AI Capitalism, then, is characterized by the extensive automation of labor, including not just manual tasks but also cognitive and decision-making processes, the centrality of data as a commodity, with companies collecting and monetizing vast troves of information to train algorithms, winner-take-most markets due to network effects and high R&D costs, leading to dominant tech conglomerates and increasing ties between big tech and the state, especially as governments seek AI advantages for national security and economic growth.

Note that my view of AI Capitalism does not require significant advances or breakthroughs over present-day technologies. It does not require sentient AI, but rather simply extrapolates current trends on a relatively predictable curve. It is entirely possible that the growth curve could be much faster—although increasing challenges with training new models, continuing problems with hallucinations, and the cost of compute and energy for that compute—suggest that is unlikely—just as it is possible that there will be barriers that will be extremely difficult to surmount. The slow implementation of full-self-driving vehicles is an example of the latter.

Financialization and inequality are another hallmark of the current era. Enormous wealth is being generated at the top of the economic pyramid, especially in finance and tech, but it’s not trickling down. Corporate profits and stock valuations have hit record highs in recent years, even as populist anger at “elites” grows. Such inequality and financialization fuel the very grievances populists leverage. Workers see the “Wall Street and Silicon Valley elite” amassing fortunes while their own jobs feel precarious. AI Capitalism promises greater productivity and new innovations, but it is also disruptive and disorienting. It is automating away livelihoods, rewarding a transnational investor class, and concentrating economic power in a few tech firms. Moreover, its key resources —data, code, capital—flow easily across borders, making it a fundamentally global system. This new paradigm has yet to fully mature or be guided by updated regulations and social contracts. National Populism can be seen as a reactive adjustment: a political attempt to grapple with these economic tremors using the familiar tools of nationalism and statism, even if, at present a tenuous alliance between the National Populist administration and AI Capitalism exists. It is unlikely to hold for much longer. AI is not merely an extension of neoliberal capitalism but a break from it. The rise of AI Capitalism represents a structural shift that National Populism cannot fully contain—one that will provoke deeper economic and political crises as AI advances.

History offers parallels that help us understand National Populism’s role as a transitional mode of regulation. The interwar period of the 1930s provides perhaps the most instructive comparison. With the Great Depression, the earlier liberal capitalism faced a profound crisis of legitimacy. That economic order, which had dominated since the late 19th century, could no longer deliver stability or growth. Into this vacuum stepped reactionary movements that mobilized workers disenfranchised by economic collapse and technological change.

These movements, particularly fascism in Europe, presented themselves as defenders of national workers against both international finance and communist revolution. Like National Populism—which directly references them—they promised to restore national greatness through economic autarky, rearmament, militaristic foreign policy, and the protection of traditional industries. Yet despite their frequent anti-capitalist rhetoric, their actual economic function was quite different. Rather than reversing industrial capitalism, they accelerated industrial concentration, technological modernization, and the development of new production methods while miring their respective economies into deeper crisis. The historical irony is that fascism, particularly in Germany and Japan, served as a bridge between liberal capitalism’s collapse and the emergence of postwar Fordism-Keynesianism. By forcibly reorganizing economic institutions and centralizing industrial capacity, it inadvertently prepared the ground for the corporatist, mass-production economy that would follow.

Political economist Karl Polanyi later analyzed this period as a kind of “double movement.” Free-market capitalism in the early 20th century had disembedded itself from society, leading to rampant inequality and instability. Society then pushed back with a countermovement demanding protection from the market’s ravages. This counter-reaction took both progressive forms (social democracy and the New Deal’s welfare capitalism) and regressive forms (fascist or ultra-nationalist regimes). In Polanyi’s view, fascism was a path where democracy was sacrificed to safeguard capitalism through authoritarian means, once liberal democracy seemed unable to cope.8

Of course, the New Deal in the United States offers a democratic counterexample to fascism’s transitional role. Facing the same global Depression, the Roosevelt administration established new regulatory frameworks, labor protections, and social welfare systems that facilitated the shift to Fordist mass production without abandoning democratic institutions. Similarly, Scandinavian countries navigated the post-WWII transition to coordinated market economies through negotiated compromises between capital, labor, and the state. These examples remind us that while economic transitions inevitably create disruptive pressures, societies retain agency in determining how those pressures are managed.

Today’s national populism can be seen as a similar search for a stopgap solution amid economic upheaval. As in the 1930s, we see widespread disillusionment with liberal elites and international cooperation. Populist leaders invoke economic nationalism—tariffs, border walls, strongman negotiation against foreign competitors—to shield people from global market shocks. In the United States, for example, Donald Trump’s administration has taken a distinctly 1930s-style approach on trade, imposing sweeping tariffs to protect domestic industries. However, these measures can at best provide only fleeting relief before they backfire. Despite tariffs on China and other nations, the overall U.S. trade deficit soared to its highest level in over a decade during Trump’s first term (the combined trade gap hit $679 billion in 2020, up from $481 billion in 2016.9 While the bilateral deficit with China shrank, U.S. companies simply shifted imports to other countries. This underscores a key point: Nationalist economic policies struggle against the structural realities of globalized production.

Today’s transition differs significantly from the 1930s, though the pattern of reactionary politics during economic transformation remains instructive, with “America First” directly appealing to quasi-fascist nativism of that era. Our moment is unique due to the fundamental break in the relationship between technology and human labor. Previous technological revolutions transformed labor without eliminating its centrality to production. This isn’t simply another step in automation but a complete restructuring of capital-labor relations, potentially rendering human labor largely superfluous to capital accumulation. This explains why conventional economic responses—neoliberal flexibility or neo-Keynesian stimulus—appear increasingly inadequate. It also explains also why National Populism will not be able to maintain its tenuous alliance with AI Capitalism and why National Populism is doomed to policy failure.

With neoliberalism unravelling, National Populism functions as a holding pattern that obscures deeper transitions to an AI-driven, increasingly post-labor capitalism. While its rhetoric centers on jobs, sovereignty, and cultural restoration, the economic forces it unleashes point in a different direction altogether—one that will ultimately make its core constituencies obsolete.

This transition explains many of National Populism’s contradictions. On the one hand, it promises to restore manufacturing jobs and industrial prosperity; on the other, it accelerates financialization and deregulation in ways that undermine those very promises. Protectionism and economic nationalism are at odds with the borderless nature of AI Capitalism, yet numerous tech leaders such as Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Palmer Luckey have aligned themselves with the movement while others, notably Sam Altman, Mark Zuckerberg, and Tim Cook have taken pains to pay tribute to Trump.

Several key tensions highlight this contradiction:

Global Supply Chains vs. Tariffs: As noted earlier, populists can slap tariffs on imports, but multinational companies often reroute rather than truly reshore production. Modern manufacturing relies on components sourced worldwide. Complex industries like AI and electronics depend on rare earth minerals from Africa, semiconductors from East Asia, and engineering talent from everywhere. Efforts to localize entire supply chains face high costs and resistance from industry.

Labor Automation vs. Job Promises: National populists frequently campaign on restoring lost industrial jobs (coal mining, steel, factory work), but the harsh reality is that many of those jobs have been eliminated more by automation than by trade. For instance, U.S. manufacturing output is near historic highs, but it employs far fewer workers than decades ago, because robots and software allow far higher productivity per worker. The push for AI and productivity improvements directly undercuts the promise of traditional jobs.

Skilled Immigration and Tech Talent: AI Capitalism is fueled by human talent – engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs often drawn from a global pool. Yet the nationalist thrust of populism includes harsher immigration restrictions and xenophobic rhetoric that can drive away needed talent. In particular, while many Indian Americans—who now dominated Silicon Valley leadership—supported Trump’s candidacy and he named Tulsi Gabbard as Director of National Intelligence and Kash Patel as Director of the FBI, anti-Indian rhetoric has increased among National Populists since the election. An uneasy tension masks a potential flare-up.

Data and the Digital Economy: Data flows are intrinsically transnational – an AI system might train on user information from millions of people across dozens of countries. Nationalist policies that demand strict data localization or “internet sovereignty” can conflict with the way digital businesses operate. The nation-state finds it hard to assert economic control when information itself ignores borders.

National Populism emerges as a transitional form managing contradictions in a system under profound transformation. Its base consists primarily of people made obsolete by neoliberalism yet unable to participate in AI Capitalism—remnants of an industrial proletariat rather than knowledge workers or financial elites. This demographic differs from both Marx’s proletariat and the neoliberal precariat, presenting capitalism’s greatest challenge since the industrial revolution. With their economic function eliminated, this class’s cultural grievance becomes weaponized political force. Their value lies in political disruption rather than economic production. Though economically redundant, they remain consumers and political actors with legitimate grievances. Yet National Populism’s solutions cannot address the technological forces causing their obsolescence, and their political mobilization ironically accelerates the transformation threatening them.

This surplus position explains National Populist leadership’s unusual relationship with its base. Unlike traditional movements promising material improvements, it offers psychological compensation—dignity, recognition, and transgressive identity politics. Leaders provide cultural and political meaning to those capitalism has discarded rather than economic salvation. This impending abandonment explains populist culture’s increasingly apocalyptic tenor. End-times thinking, conspiracy theories, and decline narratives provide psychological framework for populations sensing their economic redundancy.

Prominent economic advisers to National Populism exemplify this contradiction. The Trump administration’s first term demonstrated this pattern: corporate tax cuts, financial deregulation, and trillion-dollar deficits expanded financialization while ostensibly supporting “forgotten Americans.” In the second term, massive cuts to government programs have been accompanied by promises for further tax cuts. Far from challenging Wall Street dominance, these policies intensified the dominance of financial capital over investment in infrastructure or manufacturing. Similarly, other National Populist regimes have expanded sovereign debt while reducing capital controls, allowing financial speculation to flourish under nationalist cover.

Expanded debt—both sovereign and personal—creates the financial infrastructure that AI Capital requires. AI-driven finance depends on massive data flows, algorithmic trading systems, and complex financial products—all enhanced by the deregulatory impulses of populist governance, as well as investment capital that will be marshalled for AI development. In the meantime, vast amounts of consumer and government debt will be generated to maintain consumption as human labor becomes less necessary.

National Populism’s cultural production deserves deeper examination as it prefigures AI Capitalism’s relationship to truth and reality. The movement thrives on an algorithmic curation of reality that mirrors the digital platforms its supporters often claim to distrust. While denouncing “fake news” and mainstream media, National Populism embraces synthetic realities and alternative fact structures that erode consensus-based truth regimes. Trump himself emerged from reality television, a medium endemic to network culture where authenticity is performative rather than substantive. This collapse of real/fake distinctions itself prefigured the AI-generated media landscape now emerging.

By destabilizing conventional epistemological frameworks while failing to offer coherent alternatives, National Populism prepares society for AI-based reality systems. When truth is already fractured and institutional authority delegitimized, algorithmic authority fills the vacuum. The populist assault on expertise and traditional knowledge production thus inadvertently paves the way for algorithmic governance of information—a core feature of AI Capitalism.

To fully understand the contradictions between National Populism and AI Capitalism, we must examine the ideological movement rapidly gaining traction among tech elites: Effective Accelerationism, or “e/acc.” This movement represents a radical departure from both traditional capitalism and neoliberalism. Unlike both National Populism and neoliberalism, which at least nominally center humans in their economic vision (whether as workers or consumers), like Futurism, e/acc explicitly rejects human-centric considerations in favor of maximum technological acceleration.

E/acc represents the ideological vanguard of AI Capitalism—not merely embracing technological change but actively working to remove all barriers to its maximization. Its philosophical roots extend beyond recent tech discourse to the darker corners of 1990s critical theory, particularly the work of Nick Land, who developed an influential framework of cybernetic Lovecraftianism—viewing technological acceleration as an unstoppable, inhuman force consuming human civilization. His concept of “hyperstition” posited that certain ideas function as self-fulfilling prophecies, bringing themselves into reality through their circulation. Today’s e/acc movement, championed by figures like venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, represents a corporate-friendly version of Land’s darker vision. Andreessen’s “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” repackages accelerationist ideas without Land’s gothic aesthetics or explicit anti-humanism, but retains the core principle: technological development must proceed regardless of social consequences.10

Peter Thiel’s position within this framework is particularly revealing. Despite funding National Populist politicians, Thiel’s philosophical outlook aligns closely with accelerationist principles. His dictum that “competition is for losers” reflects the e/acc view that market competition should be transcended by monopolistic control of technological development. Elon Musk occupies an even more contradictory position. While publicly expressing concerns about uncontrolled AI development, his business practices aggressively advanced automation across multiple sectors. Notably, Grok, the LLM he had developed at X is noted for having the weakest guardrails of any model developed in the US.

When we examine how these leading tech figures have embraced right-populist movements, we see a clear pattern of strategic alignment despite apparent ideological differences. Thiel was one of the few Silicon Valley luminaries to back Donald Trump in 2016. He spoke at Trump’s convention and later served on his transition team. Thiel’s motivations connect to his long-standing critique of what he sees as the complacency of the post-Cold War establishment. His support for Trump can be understood as a desire to disrupt the old regime that, in his view, had become mired in regulatory and bureaucratic inertia. Trump’s populism, with its contempt for “experts” and norms, was a blunt instrument to weaken the existing order. Musk initially kept politics at arm’s length, but by the early 2020s, feeling slighted by the Biden administration which did not invite him to an event celebrating Detroit’s investment in electric vehicles, he increasingly echoed right-populist talking points. Musk’s purchase of Twitter (now X) and his shift to reinstating banned right-wing accounts and attacking mainstream media narratives endeared him to populist conservatives. By aligning with populists, he gains a base of fervent supporters who see him as fighting the liberal establishment. This populist fandom can be leveraged to pressure policymakers to advance a techno-libertarian agenda that benefits his enterprises. At the same time, he has been aggressive in attacking other tech leaders who he feels threaten his business interests, notably Sam Altman, CEO of the current artificial intelligence leader, OpenAI. Andreessen, too, made a similar ideological journey. Once considered a moderate tech optimist, he swung to the right in recent years amid frustrations with the regulatory state. They, along with other tech figures like former PayPal executive David Sacks, share a belief that the political establishment is overly meddlesome, imposing burdensome regulations, antitrust actions, and taxes that impede Silicon Valley’s vision.

Still, the conflict between e/acc and National Populism is inevitable even if temporarily concealed. E/acc views border controls, worker protections, and cultural conservatism as inefficiencies to be eliminated; National Populism depends on these very structures for its political identity. The current alliance exists because both movements oppose the administrative state and regulatory oversight, but for fundamentally different reasons—National Populism because it views these institutions as corrupted by globalist elites, e/acc because it sees them as impediments to technological acceleration. This temporary alignment explains why tech billionaires have become willing funders of populist movements despite their obvious ideological differences. For e/acc adherents, National Populism serves as a useful battering ram against the regulatory state—once those barriers are demolished, the movement and its human-centric concerns can be discarded. Ultimately, the National Populist base is fundamentally incompatible with AI Capitalism’s trajectory. Primarily low-skill and low-tech, this demographic faces increasing economic obsolescence within an AI-driven system. This incompatibility runs both ways. The base actively despises the very symbols of AI Capitalism, exhibiting a virulent hatred of electric vehicles and rejecting the cultural markers of technological elites, notably Tesla. After Musk’s alliance with Trump, the manufacturer has seen sales crater both in the US and worldwide.

As I pointed out earlier, the nationalist orientation of populist movements also directly conflicts with AI’s inherently global infrastructure. AI Capital demands borderless computation, global talent pools, and transnational flows of data. The economic vision of National Populism, with its emphasis on borders, national sovereignty, and protected markets, contradicts the fundamentally planetary scale that AI-driven capitalism requires to function efficiently.

David Graham noted in The Atlantic that tech elites often don’t mind the “populist assaults” on establishment corporations or institutions, because they themselves operate somewhat outside the old corporate world. The venture-capitalist mindset of Thiel, Musk, and Andreessen leads them to “like disruption. They don’t care if the old companies get turned upside down.”11 This startling insight reveals how even when populists attack Big Tech or Big Finance, they wind up helping rival tech entrepreneurs by hobbling their competitors or opening up new opportunities.

It seems clear that National Populism is not the future—it is a political interlude, a failed attempt to resist a transition that is already happening. Its economic promises are illusions, but its function is important: it provides a reactionary buffer that delays the recognition of AI-driven economic transformation. The real question is not whether National Populism can survive, but what system will replace it once it is no longer useful to those who are actually shaping the next economic order. The historical parallels I outlined earlier are instructive. Nazi Germany was a horrific regime, but economically it served as a transitional phase between liberal capitalism’s crisis and the postwar German economy. Similarly, Pinochet’s Chile served as a bridge from state-centered developmentalism to neoliberal market fundamentalism, using authoritarian political power to forcibly reshape economic institutions. National Populism similarly represents a reaction to the collapse of a prior order that inadvertently speeds up the transition to what comes next. Its anti-intellectualism and political disruption provide cover while AI consolidates its position and remakes the economy in ways that will ultimately make National Populism irrelevant. We can only hope it will be less violent than its predecessors.

The transition from neoliberalism to AI Capitalism, with National Populism as its flawed mediator, represents one of the most significant economic and political reconfigurations of our time. What remains uncertain is not whether AI Capitalism will emerge—this transition is already underway—but what form it will take and how democratic institutions might channel its development. For the National Populist base, this presents a tragic irony: their legitimate grievances about economic dispossession are channeled into a political movement that accelerates rather than addresses the forces rendering them obsolete. National Populism correctly identifies that neoliberalism’s promise of shared prosperity has failed many communities. Its critique of unaccountable elites resonates because it contains elements of truth. The hollowing out of industrial regions, the concentration of opportunity in a few coastal hubs, and the growing chasm between the technological elite and everyone else are real phenomena that demand response. Their fate represents perhaps the central political question of our time: what happens to human populations that capital no longer requires?

What has been missing, however, is a vision that can address these issues rather than channel discontent toward convenient scapegoats. The challenge for forward-looking thinkers is to develop models that harness AI’s productive potential while ensuring its benefits are broadly shared. This requires reimagining both the state’s role in managing technological change and capital’s relationship to labor in an era when traditional employment may no longer serve as the primary mechanism for distributing income. The transition from neoliberalism to AI Capitalism will likely be as tumultuous as the shift from Fordism to flexible accumulation was in the late 20th century. Just as that earlier transition generated new modes of regulation (neoliberalism) and cultural logics (postmodernism, then network culture), our current moment demands fresh thinking about how societies can navigate technological transformation without sacrificing democratic values or human welfare.

The failure of Democrats, themselves dominated by a Progressive Populist base, in the 2024 presidential elections—alongside broader struggles facing neoliberal governments globally—highlights the inadequacy of existing political and economic models. Even progressive initiatives stumbled by entangling themselves in narrow, identity-based frameworks. For example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey’s Green New Deal, and the climate provisions in Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, addressed vital environmental challenges but undermined broad appeal by prioritizing specific communities or businesses based on identity criteria. Such approaches, however well-intentioned, offered rhetorical ammunition to National Populists, who portrayed them as divisive rather than inclusive.

Indeed, both Progressive and National Populists have shared an underlying assumption of scarcity, treating economic and social resources as fundamentally limited, to be divided among competing constituencies. This scarcity mindset shapes public discourse, turning debates over essential goods like housing, healthcare, energy, and education into zero-sum struggles. The National Populist alliance with accelerationist tech elites reveals the fundamental instability of this arrangement. What comes next will depend on our collective capacity to imagine and implement more robust, equitable, and democratic responses to the AI revolution—responses that acknowledge technological change while insisting human flourishing, not technological acceleration for its own sake, must remain central.

Yet even as I wrote this piece, a promising alternative emerged in Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance. Klein and Thompson reject the scarcity mindset entirely, arguing instead for a return to a fundamentally American optimism, harnessing technological innovation to drive productivity growth and ensure broadly shared prosperity. They show how conflicts in housing, healthcare, energy, and education result less from genuine resource constraints than artificial scarcity imposed by outdated regulations, NIMBYism, and captured markets. Crucially, Klein and Thompson’s vision does not ignore equity or sustainability concerns. Instead, they argue we can achieve inclusive prosperity through ambitious, targeted reforms that prioritize growth, innovation, and democratic oversight. This abundance-oriented approach offers a path beyond the zero-sum thinking of populism or the unchecked accelerationism of tech elites. Such a pragmatic yet ambitious vision may provide the conceptual foundation for a new mode of regulation capable of managing AI Capitalism’s contradictions, guiding us toward a future where technology serves democratic values and human flourishing rather than supplanting them.

1. Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, “High Tide? Populism in Power, 1990-2020”

https://institute.global/insights/politics-and-governance/high-tide-populism-power-1990-2020.

2. Richard Wike, Moira Fagan, and Laura Clancy, “Global Elections in 2024: What We Learned in a Year of Political Disruption,” Pew Research Center, December 11, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/12/11/global-elections-in-2024-what-we-learned-in-a-year-of-political-disruption/#the-staying-power-of-right-wing-populism.

3. David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity (New York: Blackwell, 1991). For an understanding of the regulation school, see Robert Boyer, The Regulation School: A Critical Introduction (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990) and Michel Aglietta, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience (London: Verso, 2015).

4. Kazys Varnelis, “The Meaning of Network Culture,” Eurozine January 14, 2010, https://www.eurozine.com/the-meaning-of-network-culture/?pdf, originally published as “Tinklo kultūros reikšmė,” Kulturos Barai, no 9. 2009, 66-77 and, in an earlier version as “the Meaning of Network Culture,” Networked Publics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 145-164.

5. Cas Mudde, “Populism in the Twenty-First Century: An Illiberal Democratic Response to Undemocratic Liberalism,” The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy, 2020. https://amc.sas.upenn.edu/cas-mudde-populism-twenty-first-century

6. German Marshall Fund and John Judis, “Three Questions With John Judis,” German Marshall Fund US, https://www.gmfus.org/news/three-questions-john-judis

7. Nick Dyer-Witheford, Atle Mikkola Kjøsen, and James Steinhoff, Inhuman Power: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Capitalism (Pluto Press, 2019). For the discussion of a “trajectory towards a capitalism without human beings … a permanently unemployed section of the working class that consistently grows larger … [along with] the superlative growth of the surplus population…” see 140-141 in particular. On AI as infrastructural, see 30-31.

8. Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), 136–140, 245-256.

9. Doug Palmer, “America’s Trade Gap Soared Under Trump, Final Figures Show,” Politico, February 5, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/02/05/2020-trade-figures-trump-failure-deficit-466116

10. Marc Andreessen, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” Andreessen-Horowitz web site, https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/

11. David A. Graham, “The Fakest Populism You Ever Saw,” The Atlantic, July 19, 2024, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2024/07/trump-vance-fake-populism/679100/

Really fascinating read, Kazys.