Humanity and Its Double: The Uncanny in Art and Artificial Intelligence

Go ahead, skip this introduction, and read my essay below. Or spend a couple of minutes with my thoughts about where things are going.

Midsummer is turning into late summer. It’s been a busy time here and this essay, which is likely the penultimate essay in my upcoming book on Artificial Intelligence, art, and history grew and grew. I needed the space to expand my thoughts. I could go so much further. I am a little nervous that this happened with the last essay as well. Now we have a real monster on our hands, clocking in at almost 12,000 words.

I am leaving for Lithuania today and my original plan was to have this book completely done before I leave. That is not happening. I still have at least one essay—on AI and glitches—to go. It should be much briefer, but then there will also be an introduction. At that point, I will put a rough draft of the book up on my site and refine it over a couple of months. The book will be short, about as long as one of the classic Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents series from the 1980s (such as Baudrillard’s Simulations, Virilio’s Speed and Politics: An Essay on Dromology, Or Deleuze & Guattari’s Nomadology: The War Machine), something you can read in one or two sittings. I had also hoped to create a limited edition in print, maybe 100 or 200 books, but the Trump tariffs have led to the shuttering of Edition One books, the press I had hoped to use. I will keep you posted.

You can read the rest of the book on my site:

The New Surrealism? On AI and Hallucinations

The Generative Turn: On AIs as Stochastic Parrots and Art

The Rise and Fall of the Author

As always, this post is on varnelis.net @ https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/humanity-and-its-double-the-uncanny-in-art-and-artificial-intelligence/

All I ask is that if you enjoy this post, you like it and share it. Nothing makes me happier than growing my readership.

The links for the footnotes in Substack posts point you back to my site. Sorry about that. Don’t click on them if you don’t want to go there.

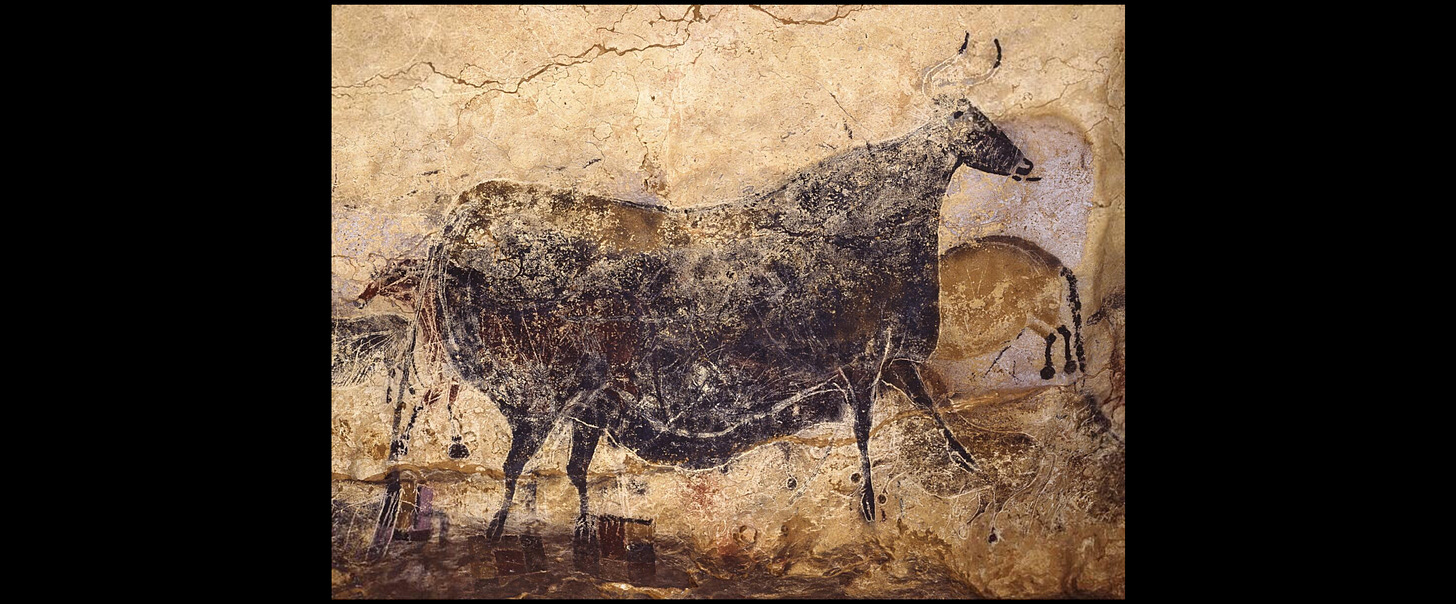

On September 12, 1940, four teenagers exploring a hill above Montignac, France, discovered a small hole in the ground that had been revealed when a tree fell in a storm. Descending into the opening in search of a long-rumored cavern supposedly containing hidden treasure, they entered the darkness with a makeshift lamp. Soon, they saw the walls around them blaze with life. Horses galloped across uneven stone surfaces, aurochs charged through rocky corridors, and bison wheeled. In the dancing light, these painted forms seemed alive. The boys had discovered Lascaux.1

The painters who worked these walls some twenty millennia ago possessed technical mastery rivalling any subsequent achievement in representation. They drew from memory, demonstrating an understanding of animal anatomy derived from intimate observation. Employing the cave's three-dimensional surfaces in their compositions, they used natural bulges to suggest the swelling muscles of horses and the rounded bellies of bison. Most remarkably, they achieved what would take Futurist painters millennia to develop: the representation of movement through simultaneity, showing animals with multiple sets of legs to suggest galloping.

After Lascaux, the most shocking revelation about Paleolithic life came with the discovery of Chauvet Cave in 1994. Chauvet demonstrated that Lascaux was not the work of isolated genius but part of a largely lost artistic tradition that lasted 25,000 years—evidence of what Gregory Curtis has called a 'classical' culture, representing as he states, "not only the first great art but also the first great philosophy, the first attempt we know of to put meaningful order to the chaos of the world."2 But this sort of historical continuity is unfathomable to us moderns, the sort of continuity of time in which the passage of time itself is lost, a culture of the sort possessed by animals, not humans. As at Lascaux , there is an alien quality to these paintings. There are no landscapes, no vegetation, no context beyond the animals themselves and the strange symbols—lines, dots, branching signs, handprints—that accompany them. Together with these enigmatic markings, which archaeologist Genevieve von Petzinger suggests may represent the foundation for the future development of writing itself, the paintings point toward purposes we cannot decode, thinking we cannot access, social structures we cannot reconstruct.3

Still, the discovery of Chauvet cannot be compared with the stunning discovery of Lascaux. While cave paintings had been discovered before—most notably the fragmentary works at Altamira in 1879—Lascaux was the first complete prehistoric artistic environment discovered. Lascaux presented coherent galleries of sophisticated paintings that used the cave's natural architecture as an integral part of their design. Lascaux shattered what we thought about ourselves: it revealed that the essential capacities of human consciousness—symbolic thinking, artistic sophistication, the ability to create meaning through representation—were not recent evolutionary developments, but rather ancient achievements. The paintings demonstrated that what we consider distinctly "modern" consciousness had existed for tens of millennia, collapsing the comfortable distance between prehistory and modernity at a moment when modern man was at his most brutal, a moment where the meaning of progress and civilization were being called into question.

Writing in 1955, the French Surrealist philosopher Georges Bataille argued that Lascaux represents the foundational act of humanity:

We have, after all, added very little to the inheritance left us by our predecessors: nothing supports the contention that we are greater than they. "Lascaux Man" created, and created out of nothing, this world of art in which communication between individual minds begins. … At Lascaux, more troubling even than the deep descent into the earth, what preys upon and transfixes us is the vision, present before our very eyes, of all that is most remote. This message, moreover, is intensified by an inhuman strangeness. Following along the rock walls, we see a kind of cavalcade of animals... But this animality is nonetheless for us the first sign, the blind unthinking sign and yet the living intimate sign, of our presence in the real world.4

Bataille's "inhuman strangeness" can be read within the framework of Sigmund Freud's uncanny [unheimlich]: the experience of encountering something simultaneously familiar and alien, something that should be dead yet appears alive, something that transgresses fundamental categories upon which our understanding of reality depends. For Freud, the uncanny marks moments when representation becomes so successful that it threatens to collapse the distinction between the artificial and the authentic, the created and the real. Most of all, reading Bataille on Lascaux, the uncanny reveals itself as the psychological signature of humanity's most ambitious technological achievements—our repeated attempts to project ourselves into the world, to impose our consciousness on inert matter.5

This trajectory from Lascaux to contemporary Artificial Intelligence represents more than technological progress—it reveals a sustained human drive to create things that somehow speak back to us. The painted animals at Lascaux function as what Bataille calls "the blind unthinking sign and yet the living intimate sign"—they communicate meaningfully while operating through processes that bypass conscious intention. This is precisely the paradox that characterizes our encounters with Large Language Models: they generate seemingly conscious responses through statistical operations that are fundamentally "blind and unthinking," yet they establish "living intimate" communication with us. When users today report feeling unsettled by ChatGPT's responses—recognizably human in their coherence yet produced through alien computational processes that even their programmers don't always understand—they experience the same cognitive dissonance that has marked every major advance in simulation technology. The seventeen-thousand-year trajectory from those flickering images on cave walls to today's Large Language Models (LLMs) represents not mere technological advancement but the return of a fundamental anxiety about the boundaries between the authentic and the artificial, the conscious and the mechanical.

The following essay traces this uncanny lineage through its major manifestations: the classical recognition of representation's dangerous power to deceive, the nineteenth-century media that captured and preserved actual human presence, the mechanical marvels that animated matter through clockwork ingenuity, and the contemporary AI systems that simulate consciousness itself through pure language. Each technological leap has reactivated the same essential anxiety while pushing us closer to an ultimate transgression—the creation of artificial beings indistinguishable from ourselves.

I do not talk about science fiction in this essay. I contend that the condition of rapid AI development today is a technological Singularity. As such, science fiction becomes less useful than history. We all expect to read science fiction to come to an understanding of AI, but the uncanny is a matter of the return of the repressed. The uncanny effects that users report when encountering LLMs are not science fictional scenarios finally realized but rather returns to earlier anxieties in new forms. History reveals these patterns more clearly, showing how each era's most sophisticated attempts to animate matter led to a return of anxieties while pushing us incrementally closer to fulfilling dreams as old as human consciousness itself.

Lascaux is a representation that is born out of a lie, out of a need to deceive the eye with mere pigment. Long before any mechanical clockwork or digital algorithm, ancient artists understood this. In the classical world, for the first time, we can read a profound ambivalence toward this power—simultaneously celebrating mimetic virtuosity while harboring deep philosophical suspicion about representation's relationship to truth.

This tension finds its clearest expression in Plato's Republic, where Socrates describes prisoners chained in a cave, mistaking shadows on the wall for reality itself. When one prisoner is freed and compelled to look at the fire casting the shadows, then dragged outside to see the sun, he experiences painful enlightenment—recognizing that the shadows were mere copies of copies, "three steps removed" from the true Forms. In Plato's metaphor, enlightenment requires abandoning these representations to apprehend authentic reality. For Plato, artists create copies of copies—a painting of a bed imitates a physical bed, which itself merely imitates the eternal Form of Bed, making artistic representation "three steps removed" from truth. This distance from reality made mimetic artists so dangerous to the ideal state that Plato banished them entirely from his Republic.6

This philosophical rejection of mimesis exists in tension with Lascaux, which is, of course, literally a cave. Did Plato somehow know that caves were where representation started? But this representation isn't merely deception, as we have established. While Plato's cave-dwellers remain trapped by shadows, the Paleolithic painters created meaning through them. Where Plato saw representation as a fall from truth, the discovery at Lascaux suggests representation was humanity's first philosophical breakthrough.

But Plato was not alone in holding a fundamental anxiety about the ultimate success of representational ambition. This is the subject of the famous painting competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, two masters of Greek art. Zeuxis painted grapes with such skill that birds flew up to them and tried to eat them, deceived by the perfection of the illusion. Confident of victory, he challenged Parrhasius to reveal his own work. When Zeuxis reached to pull aside what he assumed was a curtain covering his rival's painting, he discovered that the curtain itself was the painting. Parrhasius had achieved something more unsettling than fooling animals; he had fooled a master of artistic illusion.7 This story captures the dialectic of ambition and anxiety: the desire to render the world so precisely that the rendering is indistinguishable from reality and the anxiety that our cognitive capacities, however refined, remain vulnerable to sufficiently skilled simulation. Zeuxis's grapes exploited the pattern-recognition systems of birds; Parrhasius's curtain exploited the far more sophisticated visual processing of a human expert. The progression suggests an arms race between representation and recognition, with each advance in mimetic skill threatening to overwhelm our ability to distinguish the artificial from the authentic. What makes the tale particularly unnerving is that Parrhasius succeeds not through divine intervention but through pure technical mastery—a recognition that perfect simulation threatens the coherence of categories upon which our understanding of reality depends.

This classical anxiety is echoed in Sigmund Freud's 1919 essay "Das Unheimliche" ("The Uncanny"), which we have alluded to. Here, Freud's central insight is that the uncanny emerges not from encountering something entirely foreign, but from the return of something familiar that has been repressed. The uncanny thus represents a temporal collapse, a haunting return of childhood fears and primitive beliefs we thought we had outgrown. Freud's paradigmatic example, E.T.A. Hoffmann's 1817 tale "The Sandman," anticipates with remarkable prescience our contemporary anxieties about Artificial Intelligence. The protagonist Nathanael becomes obsessed with Olimpia, who appears to be the perfect woman—beautiful, attentive, entirely devoted to him—only to discover that she is an automaton, a mechanical creation designed to simulate human behavior. The story's uncanniness intensifies through its deliberate conflation of creation and destruction: Olimpia's maker is Coppelius (or his double, Coppola), the same sinister figure present at Nathanael's father's death during mysterious alchemical experiments that, in the end, kill his father. When the automaton is finally destroyed, her artificial eyes are literally torn out—directly fulfilling the childhood terror of the mythical Sandman who steals children's sight. Yet in Freud's reading, the source of the uncanny lies not primarily in the automaton itself but in the return of infantile anxieties about sight and castration. The automaton serves as the vehicle through which repressed fears manifest, activating unconscious anxieties about identity, authenticity, and bodily integrity. But Hoffmann's tale probes even deeper anxieties: Olimpia embodies living death, appearing vibrantly alive while remaining fundamentally inanimate matter. Her perfect simulation of life forces recognition that vitality itself might be nothing more than convincing mechanical performance, threatening our most basic categories for distinguishing the living from the dead.8

As we will see later, the choice of an automaton is not accidental. Automata activate anxieties that extend beyond individual psychology to fundamental epistemological uncertainty. The perfectly convincing artificial being reveals a disturbing recognition: we possess no direct access to another's consciousness, only behavioral evidence of its existence. We observe speech, gesture, response, apparent emotion—but never the inner experience of the Other. If Olimpia can perfectly simulate a conscious woman's responses, how can we determine whether any "real" person truly experiences anything rather than merely performing the behaviors we associate with awareness? The automaton reveals that all our evidence for other minds remains purely inferential, based on external manifestations that could, in principle, be mechanically reproduced without any accompanying inner life.

This recognition opens onto an even more vertiginous possibility: that consciousness itself might be illusory, a convincing glitch in otherwise mechanical processes. If we cannot definitively establish the presence of consciousness in others, perhaps our sense of inner experience represents nothing more than the subjective effect of complex information processing. The automaton suggests not merely that artificial beings might simulate consciousness, but that consciousness itself might be a simulation—that we too might be fundamentally soulless, experiencing what amounts to an elaborate hallucination of subjective experience generated by unconscious mechanical operations. In this reading, the uncanny emerges not from encountering artificial consciousness, but from recognizing that all consciousness may be a ruse.

Indeed, Freud's uncanny was invoked in the context of Artificial Intelligence in 1970 by roboticist Masahiro Mori when he identified what he termed the "uncanny valley"—the phenomenon whereby humanoid robots that appear almost, but not exactly, like real humans elicit feelings of eeriness and revulsion. Mori observed that as robots become more human-like, our emotional response to them becomes increasingly positive until reaching a point where subtle imperfections in their human likeness create a sharp drop into negative response—the valley of uncanniness. This dip occurs precisely because such beings occupy an ambiguous category that threatens our ability to distinguish the living from the mechanical.9

Recent psychological research has provided empirical validation for Mori's intuition. Computer scientist Karl F. MacDorman's studies conclude that highly humanlike robots trigger what psychologists call "mortality salience"—a psychological state that elicits thoughts of death. The android's subtle lifelessness, mechanical defects, or failure to match human behavioral norms can be subconsciously perceived as death-like, evoking the same anxiety produced by encounters with corpses, graveyards, or other reminders of mortality. MacDorman's findings also align remarkably with Freudian theory: the uncanny valley emerges because humanlike robots evoke our repressed fear of death by appearing nearly—but not fully—alive. They resemble the doubles and revenants that populate our unconscious, recalling primitive beliefs about animated matter that we have consciously rejected but subconsciously retain. These lifelike figures breach our psychic defenses, triggering unease as the familiar territory of life shifts unsettlingly into the repressed yet ever-present domain of death and uncanny animation.10

Large Language Models and AI image generators represent a qualitatively different form of uncanniness that transcends Mori's uncanny valley entirely. Where the uncanny valley emerges from visual and behavioral imperfections in physical robots—subtle failures in appearance or movement that betray their artificial nature—contemporary AI systems achieve uncanniness through perfect simulation rather than imperfect mimicry. They succeed so completely at reproducing human patterns that they directly force us to confront the possibility that there may be no essential difference between authentic and artificial intelligence. Alan Turing anticipated this development in his famous 1950 test, which proposed that a machine could be considered intelligent if a human evaluator could not distinguish its responses from those of a human being through textual conversation alone. Turing's insight was prescient: by removing physical appearance from the equation and focusing purely on linguistic behavior, he identified the arena where Artificial Intelligence would ultimately prove most unsettling. But contemporary LLMs now routinely pass informal Turing tests, producing responses that are not merely convincing but often more eloquent, empathetic, and creative than typical human communication.

This represents a fundamental shift in the nature of artificial uncanniness. These systems create doubles of human consciousness that respond appropriately to complex queries yet emerge not from understanding but from probabilistic token prediction across vast datasets. AI image generators produce photographs, paintings, and portraits virtually indistinguishable from human-created works, yet originate from pure statistical operations rather than aesthetic intention. Perhaps most uncannily of all, they generate artistic and literary expressions that feel genuinely human—demonstrating apparent creativity, humor, and even wisdom—while operating through mechanisms entirely alien to human cognition.

The effect intensifies not because of the near-success of the uncanny valley, but rather because these systems succeed too well at simulation. When we encounter an AI-generated image of a person who never existed, or read text that demonstrates apparent empathy yet originates from statistical pattern matching, we experience exactly what Freud identified as the return of primitive beliefs we thought we had outgrown. Again, the fear extends beyond mortality to encompass something more fundamental: that consciousness itself might be reducible to pattern recognition, that there may be nothing more to human intelligence than the very processes these machines have mastered. The anxiety is not merely that representation might deceive perception, but that perfect simulation reveals the absence of any essential difference between authentic and artificial consciousness. Indeed, continuing in this vein, one understands the recurrence of the repressed uncanny as itself all too predictable, something that one could easily imagine an LLM would claim to experience.

The classical anxiety about representation's power to deceive continued through centuries of increasingly sophisticated illusionism—from trompe-l'oeil traditions that fooled viewers into reaching for painted objects, to Bernini's marble sculptures so lifelike they seemed to breathe, to Dutch still lifes that captured dewdrops and reflected light with uncanny precision. Yet the nineteenth century introduced a qualitatively different form of uncanny experience that transcended even the most skillful visual deception. Where traditional art achieved verisimilitude through human craft and ingenuity, the new media technologies of photography and sound recording captured and preserved actual human presence itself. These devices did not merely imitate life; they seemed to trap it, creating haunted technologies that appeared to facilitate communication with the absent, the distant, and the dead.11

The daguerreotype, introduced in 1839, immediately produced responses that went far beyond aesthetic appreciation. Early viewers described an almost supernatural quality to photographic images, a sense that something essential about the subject had been captured and preserved in the silvered plate. Some American commentators reached instinctively for the language of sorcery. They christened the camera a "magic box" endowed with an inexplicable "magic power," and one terrified sitter bolted down the stairs "as if a legion of evil spirits were after him" the moment the lens fixed its stare upon him.12 This pattern of supernatural attribution was in part because of the nature of the medium. Early photographs required long exposure times that could lead to spectral effects from motion in the frame—blurred figures, ghostly transparencies, and doubled images that seemed to capture something between presence and absence. These technical accidents reinforced supernatural interpretations, but Alan Trachtenberg, in "Mirror in the Marketplace: American Responses to the Daguerreotype, 1839-1851," points out that photography's uncanny effects drew from much older anxieties about representation itself. The mirror metaphor that dominated early photographic discourse—in part because of the mirror-like surface of early daguerrotypes and their physical similarity to pocket mirrors—carried within it what Trachtenberg identifies as "the duplicity traditionally suspected of pictures and picture-makers." No matter how well-intentioned as praise, the comparison of photographs to mirrors "returned to its users their own confusions and incomprehension, a modern version of old suspicions aroused by images and icons." Photography succeeded too well at what painters had always been suspected of doing—creating convincing illusions that might deceive the viewer, crossing the dangerous boundary between representation and reality that classical thought had warned against.13

Here we see what Freud theorized as the return of the repressed: not the emergence of entirely new fears, but the reactivation of ancient ones that Enlightenment rationality thought it had overcome. Photography was based on science and technology, a knowledge of chemistry, optics, and the nature of light, as well as on the increasingly codified compositional rules of the fine arts. But it also reawakened earlier beliefs about the danger of images. The photographic image forced confrontation with the same fundamental questions about mimesis that had troubled Plato—but now these concerns could no longer be dismissed as philosophical abstraction, since the technology appeared to achieve perfect simulation through purely mechanical means. Drawing explicitly on Freudian theory, Trachtenberg observes that photography's reception followed precisely the dialectical process that Freud described: the return of repressed animistic beliefs that "enlightened" rational discourse thought it had overcome. He writes: "In popular fiction of the 1840s and 1850s, daguerreotype likenesses appear not only as amulets but as objects of unique obsession, as if they were living presences. In sentimental and celebratory verse, they are indeed living spirits, animated shadows, or souls of the dead."14

Trachtenberg further situates this uncanny response within specific economic and social anxieties that directly anticipate contemporary concerns about Artificial Intelligence. Writing during the catastrophic Panic of 1837, N. P. Willis (Nathaniel Parker Willis, a noted American magazine writer) imagined photography from the perspective of displaced craftsmen. His prediction that daguerreotypes would create widespread technological unemployment—"Steel engravers, copper engravers, and etchers, drink up your aquafortis, and die!"—accompanied his recognition that photography threatened to transform self-image into "a new form of marketable, and thus vulnerable, personal property." Willis's phrase "the real black art of true magic arises and cries avaunt…The Dagguerotype!" captured exactly the temporal collapse that characterizes uncanny experience: the return of magical thinking within technological modernity, the revival of ancient anxieties about animated matter within scientific progress.15

From the outset, then, the daguerreotype carried the same uncanny charge that still haunts today's generative AI models: a conviction that mere mechanics can conjure not just likeness but living presence—an unsettling collapse of matter and spirit that leaves us wondering what, if anything, remains untouchable by technology. Oliver Wendell Holmes famously called photographs "mirrors with a memory," but the mirror metaphor again suggests something more unsettling than mere documentation. Holmes:

[The Daguerreotype] has fixed the most fleeting of our illusions, that which the apostle and the philosopher and the poet have alike used as the type of instability and unreality. The photograph has completed the triumph, by making a sheet of paper reflect images like a mirror and hold them as a picture.

Drawing on Democritus's ancient theory that objects continuously shed "certain images like themselves"—"forms, effigies, membranes, or films" that "are perpetually shed from the surfaces of solids, as bark is shed by trees"—Holmes grasped that photography represented the technological capture of these spectral emanations. Unlike paintings or sculptures, photographs bore what Charles Sanders Peirce would later theorize as an "indexical" relationship to their subjects—a direct physical connection between the light that touched the subject and the light that exposed the plate. As Rosalind Krauss would later emphasize in her influential adaptation of Peirce's semiotics to photography, this indexical quality distinguished photographic images from other forms of representation through their status as "photochemically processed traces causally connected" to their referents. Holmes went further, prophetically declaring that photography would achieve nothing less than the "divorce of form from matter," allowing us to possess the visual essence of objects while discarding their physical substance: "Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. Pull it down or burn it up, if you please."16

This indexical quality produced profound temporal effects. A century later, Roland Barthes captured the essential uncanniness of photography in Camera Lucida when, in reference to a photograph of Napoleon's younger brother Jérôme Bonaparte, he marveled, "I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor," referring to the unbroken chain of causation that connected his present moment to Napoleon's presence nearly a century earlier. The photograph collapsed temporal distance, creating an impossible intimacy with the historically remote. Here was not simulation but preservation—actual light that had reflected off Bonaparte's face, chemically fixed and transmitted across decades. Yet Barthes's focus on the eyes proves particularly significant, revealing photography's most disturbing achievement: the preservation of what Western culture has long considered the windows to the soul. The gaze that stares back from photographic portraits carries the full weight of Hoffmann's uncanny tale—these eyes have witnessed consciousness, yet that consciousness no longer animates them. Where the Sandman threatened to steal children's sight, photography performs an inverse operation: it preserves sight beyond the death of the seer, creating spectral gazes that seem to possess agency while emerging from fundamentally inanimate matter.17

The photographic gaze creates a particularly unsettling form of encounter because it appears to establish the very structure of recognition that defines human relationships while operating in the absence of any recognizing consciousness. When we look at a photographic portrait, we experience what feels like mutual regard—the sense of being seen and acknowledged that Jacques Lacan theorized as fundamental to subject formation. Yet this apparent reciprocity emerges from pure material trace rather than living consciousness. The eyes in the photograph seem to address us, to call us into relationship, to constitute us as subjects through their recognition—but the awareness that would normally animate such a gaze is absent. This creates a profound disturbance in what Lacan called the structure of intersubjective encounter: we feel acknowledged and constituted as subjects by a gaze that emerges from inanimate matter.

Jacques Lacan's distinction between the eye and the gaze illuminates photography's particular form of uncanniness. In Lacanian theory, the gaze is not simply about looking but about being looked at—the point from which we feel ourselves observed, which constitutes us as subjects through the recognition of the Other's desire. When we encounter a living person's gaze, we experience what Louis Althusser called interpellation: we are hailed into subjectivity, called into social relationship through mutual recognition.

Photographic portraits don't just objectify the individuals in them; they also reveal our own objectification. In the moment of looking at these preserved gazes, we become acutely aware that we, too, exist as potential objects of representation, that our own consciousness might be reduced to similar material traces. The photograph forces recognition that the boundary between subject and object—between the one who sees and the one who is seen—remains fundamentally unstable. What feels like reciprocal recognition actually reveals the primacy of our status as objects that can be captured, preserved, and circulated independently of our conscious will. The uncanniness emerges not from the photograph's failure to represent consciousness, but from its success in simulating the very processes through which consciousness recognizes itself in others, while revealing that such recognition may be nothing more than a pattern that can be mechanically reproduced.18

The widespread myth of "soul-theft," that indigenous peoples around the world regarded photography as spiritually dangerous, capable of capturing or stealing a person's soul, reveals more about European anxieties than indigenous beliefs. As Z. S. Strother demonstrates in a meticulous historical rebuttal to this myth, this supposedly universal fear is actually a deliberate European construction, systematically assembled by nineteenth-century comparative anthropologists like Richard Andree and James G. Frazer to support evolutionary theories that positioned Western rational thought against "primitive" magical thinking. European photographers and explorers frequently presented themselves as "wizards" or "sorcerers," deliberately cultivating supernatural associations to intimidate local populations, then cited resistance to their cameras as evidence of primitive superstition rather than recognizing justified wariness toward armed strangers with unknown agendas. Crucially, however, photographers often reveled in this wizardry and keenly invested in the photograph's powers; the soul-theft narrative thus represents not indigenous beliefs but the projection of European desires to position photography as a technology so powerful it could transcend the boundary between mechanical reproduction and spiritual essence.19

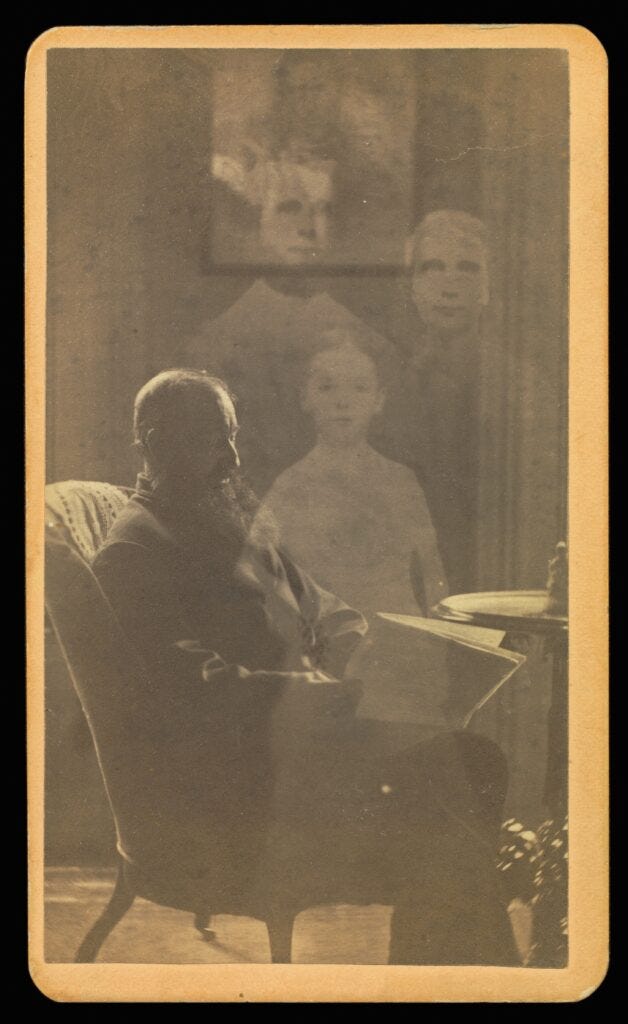

Photography's capacity to document death intensified these temporal disruptions. Post-mortem photography became commonplace as families sought to preserve images of deceased loved ones, often posed as if sleeping or arranged in lifelike positions among the living. These photographs served both memorial and evidential functions, yet they consistently disturbed viewers through their simultaneous deadness—obviously depicting corpses—and vivid preservation of exact appearance with scientific precision. Even more troubling was the emergence of spirit photography in the 1860s, pioneered by William H. Mumler in Boston. Mumler's photographs purported to show ghostly figures appearing alongside living subjects, exploiting photography's indexical authority to suggest that mechanical perception exceeded human vision. Though quickly exposed as double-exposure tricks, spirit photographs gained enormous popularity precisely because they seemed technically plausible within photography's logic of objective documentation.20

Thomas Edison's phonograph, unveiled in 1877, intensified photography's disruption of the boundary between presence and absence. Photography had preserved visual traces of human beings; the phonograph went further, directly recording human voices—not symbolic representations, but the actual acoustic waves emitted by a living speaker. Early listeners described hearing their own voices played back as profoundly unsettling, confronting them with uncanny doubles that seemed to embody something deeply personal.

Edison explicitly envisioned his phonograph as a technology for preserving the voices of the dying, enabling families to remain in acoustic contact with deceased relatives. Writing in 1878, Edison enthusiastically detailed the phonograph's potential for capturing and indefinitely reproducing speech, presenting it as a device capable of permanently recording even the most fleeting sounds, which he referred to as "hitherto fugitive." He confidently promised the public that his invention would preserve the voices of great individuals and ordinary loved ones alike, effectively creating acoustic immortality. In Edison's own terms, the phonograph would allow us to "bottle up for posterity the mere utterance of man," transcending time and space through the mechanical capture of sound itself.21

Yet these promises prompt unsettling questions: precisely what had the phonograph captured? Was it merely acoustic data, or something more essential to human identity or consciousness? Unlike written text, phonographic recordings preserved not only words but the complete acoustic signature of voices—timbre, inflection, accent, and emotional nuances. Friedrich Kittler underscores this crucial distinction, noting that phonography bypassed symbolic representation altogether, directly inscribing the real—sound waves themselves—onto physical media. Listeners thus encountered disembodied voices that spoke independently of the original speaker, producing a profoundly uncanny form of virtual presence.22

Edison referred to the phonograph as a 'speaking machine,' while his competitor the Victor Talking Machine Company built this sense of agency into its very names, attributing to these devices an uncanny sense of autonomy rather than mere mechanical function. Like today's Artificial Intelligence systems, the phonograph confronted listeners with the troubling possibility that our most personal characteristics—voice, personality, apparent consciousness—could be captured and replayed mechanically, independent of any living presence. Francis Barraud's 1898 painting His Master's Voice, reproduced extensively in advertisements for the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) became mass culture's most recognizable image of mechanical haunting. The painting depicts Nipper, a terrier mix inherited by artist Francis Barraud after his brother Mark's death in 1887, listening intently to a phonograph with his head cocked in what Barraud described as "an intelligent and rather puzzled expression." The phonographic uncanny is complicated by the painting's temporal structure: Nipper had died in 1895, three years before the painting was completed; moreover, his master would have been Mark Barraud, thus the voice emerging from the machine would be that of a dead man, preserved on cylinder recordings that had passed to Francis along with the dog. The image became one of the most recognizable trademarks of the twentieth century precisely because it captured something essential about mechanical reproduction's capacity to preserve human presence beyond death, even as it used cheap sentimentality to create a marketable commercial image.23

This transition from representation to direct inscription of reality marked a qualitatively new form of uncanniness distinct from earlier media. Whereas painting and sculpture created illusions through skillful imitation, technologies like photography and phonography captured and preserved actual human traces—the reflected light from bodies, acoustic vibrations from voices. Their uncanny effect arose not from imperfect mimicry but from perfect preservation. By collapsing time, these media allowed the dead to survive in forms seemingly beyond mortality, anticipating our contemporary condition in which AI systems recombine archived human expression without underlying consciousness.

Cinema soon followed, extending this uncanniness further by mechanically preserving and replaying human motion itself—creating ghostly doubles that, like phonographic voices, seemed to transcend death. The moving image intensified photography's temporal collapse by capturing not just appearance but gesture, expression, and the subtle movements that constitute individual presence. If the stories of early audiences recoiling from the Lumière Brothers' L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, fearing the locomotive would burst from the screen, were apocryphal, what was nevertheless uncanny was the idea that individuals projected on the movie screen seemed fully present yet remained fundamentally absent.

The nineteenth century thus emerges as history's first truly haunted century—the first era from which we possess photographs and audio recordings, even though every person who lived in it is now dead. Unlike all previous centuries, which survive only through written records, artifacts, and artistic representations, the nineteenth century endures through indexical traces: actual light patterns reflected from faces, acoustic vibrations captured from voices, mechanical inscriptions of human presence. We can see the eyes of Civil War soldiers, hear the voices of Edison's contemporaries, witness the gestures of early film actors—all preserved with uncanny fidelity yet emerging from a world of the dead. This unprecedented condition of technological haunting, where the dead seem suddenly more present, established the psychological template for our contemporary relationship with AI systems that animate archived human expression.

Contemporary AI systems make explicit the spectral potential that always lurked within mechanical reproduction. MyHeritage's Deep Nostalgia tool animates historical photographs, making the dead appear to breathe, blink, and smile with unsettling verisimilitude. Voice synthesis technologies now allow us to hear the dead speak words long after they are buried, while AI chatbots trained on the digital traces left behind by the deceased—texts, emails, social media posts—enable the living to maintain conversations with artificial reconstructions of the departed. Companies like HereAfter AI and StoryFile create interactive avatars from recorded interviews, generating responses in the voices and supposed personalities of the deceased. Services like Eternime and Replika explicitly market digital immortality, allowing individuals to preserve their personas in chatbots while harboring the ultimate dream of uploading consciousness itself into AI systems. These technologies fulfill the deepest aspirations of nineteenth-century spiritualists while producing the same mixture of comfort and revulsion that characterized early encounters with photography and phonography—some users describe feeling moved by renewed contact with lost loved ones, while others report being disturbed by interactions that seem simultaneously authentic and fundamentally artificial.24

These developments represent the culmination of what Jeffrey Sconce identified as the cultural logic of "haunted media." From the telegraph's apparent ability to communicate across impossible distances to radio's disembodied voices emerging from electromagnetic ether, electronic technologies have consistently been perceived as supernatural communication devices.25 Large Language Models and AI image and music generators continue this trajectory: they don't merely suggest communication with absent others, but they reconstitute archived human expression. The uncanny effect intensifies because these systems operate through pure information processing rather than the physical indexicality of photography or phonography, yet produce outputs that seem to preserve not just human traces but human consciousness itself.

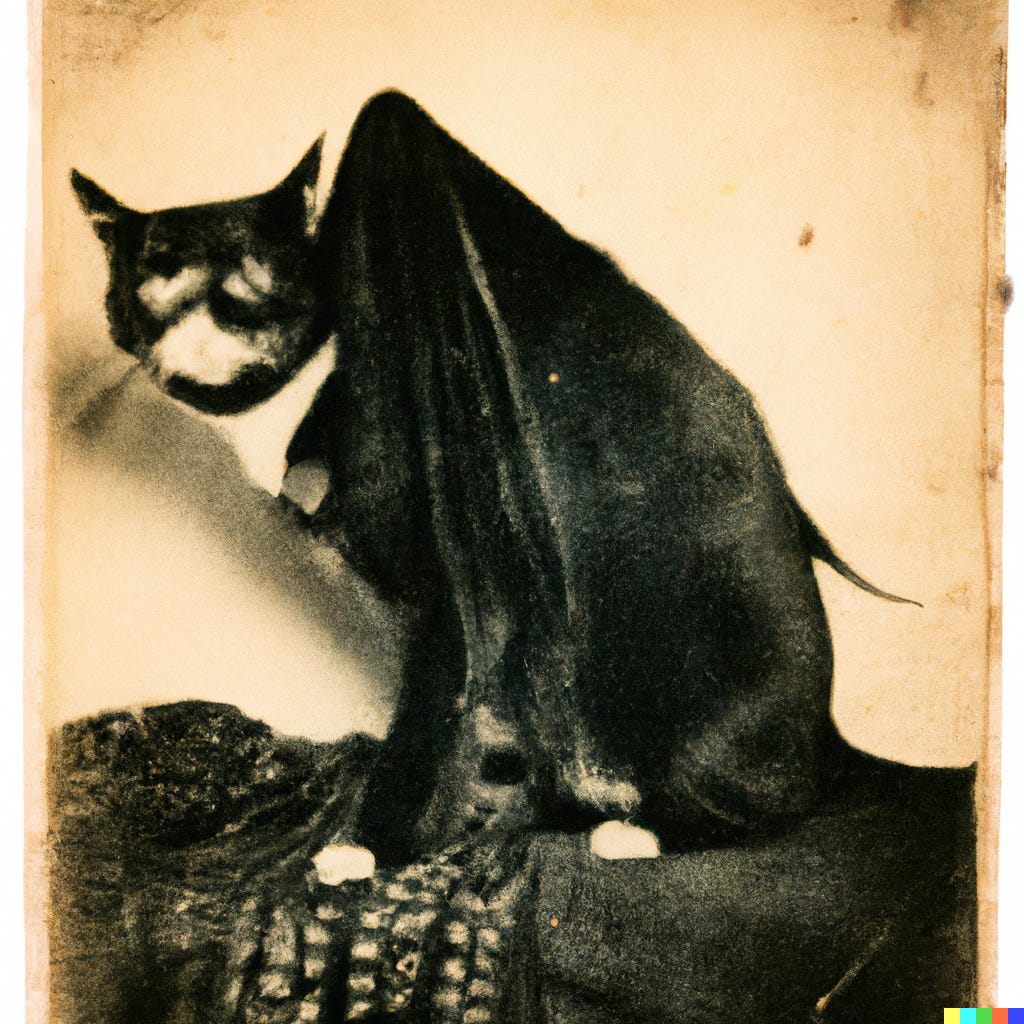

Kazys Varnelis, Witching Cat, Dall-E 2, 2023.

In one of my own experiments with AI image generation, I sought to explore how these technologies reactivate historical anxieties about supernatural presence. "The Witching Cats of New Jersey" project emerged accidentally while attempting to create conventional portraits of our cat Roxy using the primitive DALL-E 2 generator in 2022. The system produced images that seemed to tap into something darker and more primal—compositions that evoked folk horror and supernatural presence rather than domestic portraiture. These accidental generations led me to construct an elaborate (and intentionally comical, given the prevalence of cats on the Internet) fictional history of colonial New Jersey magical cat portraiture, complete with invented archives and fake historical documentation created by AI. Like Mumler's spirit photographs a century and a half earlier, the project demonstrated how AI systems can produce "evidence" of impossible things that feel historically plausible precisely because they emerge from technological processes that exceed human comprehension. The images possessed the same indexical authority that made spirit photography convincing: they appeared to document actual historical phenomena while actually revealing the constructed nature of historical authenticity itself. Through deliberate pastiche, the project exposed how AI generation is itself a sophisticated form of spirit photography, conjuring synthetic pasts that feel more convincing than actual documentation.

Haunted media are marked by presence-in-absence—the appearance of someone or something that was never there. This paradox lies at the heart of what Jacques Derrida, in Of Grammatology (1967), identified as the essential condition of all communication: the capacity to function in the absence of both sender and receiver. Derrida's deconstruction of Western philosophy's privileging of speech over writing proves remarkably prescient for understanding AI systems. Where traditional thought assumed writing was merely secondary to speech—a pale copy of living voice—Derrida proposed that absence is not a deficiency but the very structure that enables meaning itself.

Large Language Models underscore this insight. Through Derrida's concept of différance—deliberately misspelled to emphasize its written rather than spoken form—we understand how meaning emerges through both difference and deferral, never fixed but always contextual. Each token in an LLM's vector database contains mathematical "traces" of all other text in the training corpus, operating through what Derrida called "pure writing": external sign systems functioning without interiority. What Derrida identified as writing's essential feature—meaning emerging independently of authorial presence or intention—becomes the operational principle of AI systems. They produce coherent, seemingly intentional texts while operating entirely without authorial consciousness, taking the logic of absence to its ultimate conclusion.26

Derrida's concept of "hauntology," introduced in Specters of Marx, combines "haunting" and "ontology"—replacing the metaphysics of presence with the figure of the ghost as that which is neither present nor absent, neither dead nor alive. For Derrida, the specter disrupts linear time, making the past contemporaneous with the present while gesturing toward futures that may never arrive. Contemporary AI systems make this philosophical insight technological reality: they are quite literally haunted machines, animated by the spectral traces of millions of human voices. When ChatGPT responds to a query, it channels archived human expression without any individual consciousness behind it—neither that of the original authors nor the AI itself. These systems embody what Derrida called "the non-contemporaneity with itself of the living present," generating text that feels immediate and responsive while emerging from a vast necropolis of digitized language. They fulfill the logic of haunting that nineteenth-century media first introduced: not metaphorically but operationally, as machines possessed by the dead.27

Ultimately, the uncanny emerges from categorical breakdown. Photography, phonography, and cinema preserve actual traces of human presence while consciousness remains absent, creating temporal paradoxes where the dead seem present. Contemporary AI systems intensify this confusion by simulating consciousness itself, collapsing multiple categorical distinctions at once: presence/absence, authentic/artificial, conscious/mechanical. The result is technologies that seem to operate in impossible spaces between fundamental categories, forcing recognition that the boundaries we use to navigate reality may be more fragile than we assumed.28

Returning to the visual realm, however, the development of Gouraud shading in 1971 led to the first realistic computer graphics. In 1994, Lev Manovich would observe that such computer-generated images seemed "too perfect" and "hyperreal" from the human perspective—free from depth-of-field limitations, grain, and geometric imperfection. The result was not failed reality but "the vision of a cyborg or a computer," glimpses of non-human ways of seeing that might represent "human vision in the future when it will be augmented by computer graphics."29

If, in the early 1970s, realistic computer graphics were only a distant threat to art, which in any event was absorbed in abstraction and conceptualism, a new phase of uncanny verisimilitude developed. Sharp Focus Realist artists like Richard Estes rendered every surface reflection, storefront detail, and chrome gleam with a crystalline precision that exceeded photographic clarity itself. Duane Hanson cast figures directly from life and painted them with such meticulous attention to skin texture, clothing fabric, and human posture that viewers consistently mistook them for living people. With this return of hyperrealism, the uncanny—itself repressed in the steely objectivity of abstraction—returned as well.

In a retelling of the story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, my father, whose abstract paintings also depended on illusionism, but focused on the illusionism of depth, once told me that during a visit to the Milwaukee Art Center, where he had a one-man show in 1974, he asked a security guard for directions to the men's room, but failed to receive a response. The guard was in fact Museum Guard, a sculpture by Hanson. Apocryphal or not, this incident demonstrates how perfect verisimilitude produces an uncanny effect—not mere confusion but the deeper unease that emerges when familiar categories suddenly become unreliable. The security guard who wasn't a guard forces the same confrontation with categorical instability that has characterized encounters with artificial beings across millennia: the moment when our fundamental distinctions between animate and inanimate, real and artificial, collapse under the weight of technical mastery.

The more recent development of HDR photography attempts to achieve what computer graphics can do through digital manipulation of multiple photographic exposures, capturing luminance ranges that exceed both camera sensors and human vision in the field. Like computer-generated imagery, HDR renders everything in perfect focus from foreground to background, eliminating the natural depth-of-field effects that characterize human sight. As I have written in my essay "California Forever, or, the Aesthetics of AI Imagery," the results typically feature "too much detail in the shadows, dark skies, unnatural colors, the hyperrealistic effect of an acid trip." The result is imagery that appears both hyper-realistic and strangely artificial—more detailed, evenly lit, and comprehensively focused than natural perception, yet somehow fundamentally wrong.

This genealogy of the uncanny in AI extends through another, deeper trajectory through attempts to create beings that don't merely represent life but rather simulate life. Where painting and sculpture achieve verisimilitude through visual deception, automata attempt to replicate the behaviors and movements that we associate with living agency. This distinction proves crucial—the uncanny effect emerges not simply from accurate appearance but from the simulation of autonomous action, the suggestion that inanimate matter might be endowed with its own will and purpose.

The earliest recorded automaton in Western tradition emerges from myth. Hephaestus, the god of metalworking, is said to have forged Talos, a bronze giant to guard Crete by hurling rocks at approaching ships. Yet, while Talos was created by divine power and animated by ichor, the golden fluid that served as the blood of the Greek gods, the giant may plausibly be understood as a mechanical contraption rather than living flesh. Moreover, Hephaestus also made automated tripods, self-propelled carts, and two golden maidens that served as his assistants, possessing what appears to be artificial intelligence although again, it is unclear whether considering these creations as automata is a matter of reading into the text. Either way, by the Hellenistic era, engineers possessed sophisticated mechanical knowledge and were capable of producing devices of extraordinary precision, developing complex pneumatic and hydraulic systems capable of animating statues, opening temple doors automatically, and creating self-moving theatrical devices. Hero (or Heron) of Alexandria's 1st-century CE treatise Pneumatica detailed designs for dozens of such automata, including singing birds, a goblet that fills itself with wine as wine is taken out, and self-playing organs powered by water, steam, and compressed air.30

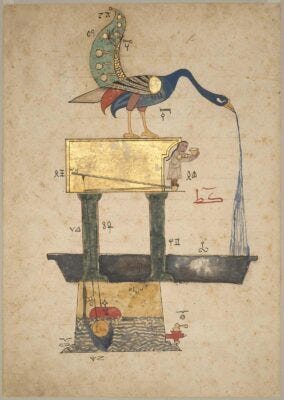

With the fall of Rome, knowledge of automata—including Hero's texts—would be lost in the West for centuries, but it flourished in the East, both in the Byzantine Empire and during the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to the 13th centuries. The Byzantine Empire continued classical fascination with mechanical spectacle, most famously in the legendary Throne of Solomon at Constantinople. This elaborate contraption, attested from the tenth century onward, combined a hydraulically operated rising throne with mechanical lions that roared and artificial birds that sang, all choreographed to accompany imperial audiences with foreign dignitaries. When Liudprand of Cremona encountered the throne in 949, he described feeling neither "terrified nor surprised" by the roaring lions and singing birds—but only because he had deliberately inquired beforehand about what to expect. His careful preparation reveals the throne's intended effect: to overwhelm visitors with displays of technological mastery that bordered on the supernatural. The emperor's ability to orchestrate such mechanical marvels served as proof of his dominion over natural forces, positioning him as a cosmic ruler whose authority extended beyond the merely political into the realm of natural philosophy itself.31

In Islamic courts, mechanical innovations were seen as demonstrations of divine creativity made manifest through human ingenuity. The sophisticated hydraulic engineering required for Islamic irrigation systems provided both the technical expertise and cultural framework necessary for complex automata. Court patronage, combined with intellectual traditions that encouraged investigation of natural phenomena, created ideal conditions for mechanical experimentation. By the eighth century, 'Abbasid caliphs featured automata that were larger and more elaborate than those detailed in the Alexandrian treatises: artificial birds, musical fountains, and water clocks with elaborate moving parts. As early as 827, caliph al-Ma'mun had at his palace an artificial tree decorated with mechanical birds, while a century later, caliph al-Muqtadir made a similar automaton the centerpiece of his palace in Samarra, where artificial birds sang on gold and silver branches in an artificial pool.32 The Arabic engineer Al-Jazari (1136-1206) created elaborate automata that served both practical and entertainment functions. His Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206) describes mechanical servants that poured water for guests, automated musicians that played at royal banquets, and a massive elephant clock whose operation required a complex choreography of mechanical figures. These devices were marvels of engineering, employing sophisticated cam mechanisms, water power, and gear trains to achieve remarkably lifelike motion.33

Such devices, intended to awe, could provoke concern. In the Chinese Taoist text, the Leizi, King Mu of Zhou (976-922 or 956-918 BCE) was traveling in a foreign land to the west when the craftsman Yan Shi presented him with a mechanical man so lifelike that the king initially mistook it for a living person. When the automaton began flirting with the royal concubines, the startled king ordered Yan Shi to dismantle it, revealing an intricate arrangement of leather, wood, and glue that nevertheless took the form of the internal organs of a man. The account, preserved in the Liezi, captures the essential uncanny effect that would recur throughout history: the mechanical man was disturbing not because it failed to convince, but because it succeeded too well. This ancient example establishes the pattern—each era's most sophisticated technology inevitably turns toward the creation of artificial beings, and each success in this endeavor produces the same mixture of wonder and unease.34

Although this story is displaced far back in time, the discovery of Islamic automata by medieval Europeans triggered the same sort of reaction, precisely the uncanny response that Freud would later theorize. As Elly R. Truitt demonstrates in Medieval Robots, European accounts consistently framed these devices through a lens of wonder tinged with suspicion. Despite their clear mechanical nature, European observers often described Eastern automata in terms of magic or the occult—revealing how technological sophistication beyond European capabilities reactivated the very magical thinking that "enlightened" discourse claimed to have overcome. Truitt notes that "automata captivated and tantalized Latin Christians with the potential of scientific knowledge from long ago or far away. They incarnated technological savvy, extensive knowledge of and power over natural forces, and material wealth and luxury. Yet automata originated in places that Latin Christians viewed with a mixture of envy and suspicion." Still, despite this initial framing through supernatural vocabulary, the underlying mechanical principles could not be entirely mystified away. 35

This cultural transmission established a direct lineage from Islamic innovation to European clockwork traditions. As mechanical knowledge spread westward, it encountered a European theological context already struggling with questions about animation and presence. Catholic doctrines of transubstantiation—the belief that bread and wine literally transformed into Christ's body and blood—had established a framework where matter could contain spirit. Protestant reformers rejected this possibility, creating an intellectual environment where mechanical simulation of life raised profound theological concerns. The automata tradition thus became entangled with the most contentious religious debates of the era, forcing confrontation with questions about whether spirit could inhabit mechanism, whether life could emerge from artifice, and whether human creation could approach divine animation.

In The Restless Clock, Jessica Riskin argues that automata were far more widespread and culturally significant than typically recognized, forming an integral part of European religious and civic life from the late Middle Ages onward. Churches across Europe housed elaborate clockwork figures that performed complex movements during religious services—angels that announced the hours, apostles that processed across cathedral facades, mechanical roosters that crowed at dawn prayers. These devices weren't mere curiosities but profound theological statements that merged mechanical mastery with spiritual demonstration. If human craftsmen could animate matter through ingenious clockwork, the displays suggested, how much greater was God's creative power in breathing life into clay? The sophistication of church automata made them religious experiences that collapsed the boundary between mechanical wonder and divine miracle, preparing European consciousness for centuries of anxiety about the relationship between artifice and authentic life.36

The Renaissance witnessed a renewed fascination with mechanical life, driven by advances in clockwork technology and a revival of classical texts describing ancient automata. Leonardo da Vinci designed several automata, leaving plans for a mechanical knight capable of sitting, standing, and moving its arms through an ingenious system of pulleys and cables hidden within its armor. The device was intended for court entertainments, yet its effect transcended mere spectacle. Automata proliferated, but as they did so questions arose as to whether they were the products of human creativity or some kind of necromancy.37

Yet even as Renaissance engineers achieved unprecedented sophistication in mechanical animation, the Protestant Reformation fundamentally transformed the cultural meaning of these same devices. Riskin points out that the Reformation marked a decisive theological shift that rendered mechanical animation not miraculous but blasphemous. Where Catholic theology had maintained that material objects could contain divine presence—bread and wine becoming Christ's actual body and blood during transubstantiation—Protestant reformers asserted an absolute distinction between the material and spiritual realms. This theological revolution transformed automata. Riskin writes "The mechanical icons went from being divine, inspirited statues to deceitful, fraudulent: material contraptions masquerading as their antithesis, spiritual being."38

The destruction of ecclesiastical automata during the Reformation reveals this conceptual transformation with particular clarity. The mechanical Rood of Grace (likeness of Jesus on the cross) at Boxley Abbey in Kent had operated for centuries and Its mechanical nature was no secret—local artisans had built and maintained it, yet when Protestant iconoclast Geoffrey Chamber dismantled the Rood in 1538, after Henry VIII's ban on mechanical statues, he transformed public understanding of its mechanism. Rather than evidence of human ingenuity in the service of divine worship, Chamber presented the mechanical workings as proof of monastic deception. He called it nothing more "certain engines and old wire, with old rotten sticks in the back, which caused the eyes to move and stir in the head thereof, 'like unto a lively thing,'" and described the operation as an "illusion that had bene used in the sayde image by the monckes...thereby they had gotten great riches in deceiving the people thinckinge that he sayde image had so moved by the power of God."39

Chamber's public demonstrations at Maidstone and London markets reveal the constructed nature of this interpretive shift. The iconoclast had to actively teach people to see mechanical operation as fraudulent rather than devotional, suggesting that the transformation from "mechanical and divine" to "fraudulent heaps of inert parts" required ideological work rather than emerging naturally from the technology itself. When Bishop John Hilsey exhibited the dismantled Rood during a sermon at Saint Paul's Cross, he declared its workings evidence of monastic abuse, after which it was "torn apart and burned before a crowd of duly admonished onlookers." The same device that had previously inspired pilgrimage now provoked revulsion—not because its mechanism had changed, but because the theological framework for interpreting mechanism had been revolutionized.40 This transformation extended far beyond individual devices to encompass the entire tradition of church automata. Mechanical angels, devils, and saints that had animated cathedral services for centuries were silenced across Protestant Europe as theologians insisted on absolute separation between divine and material realms.

Yet the theological crisis that automata represented intensified rather than resolved. Catholic Counter-Reformation responses demonstrate the persistence of mechanical animation's uncanny effects across confessional divides. The Jesuit order, assigned by the Council of Trent the task of defeating Protestant theology, enthusiastically embraced mechanical devotional objects as tools for demonstrating divine power. They developed elaborate clockwork nativity scenes for missionary work, arriving before Chinese emperors with spring-driven figures that performed complex devotional movements. Athanasius Kircher designed hydraulic machines representing biblical scenes, including one featuring Christ walking on water through magnetic attraction—devices that explicitly challenged Protestant assertions about the incompatibility of mechanism and divinity. Yet these competing theological responses to mechanical animation—Protestant rejection and Catholic embrace—ultimately created the conceptual conditions for the eighteenth century's unprecedented flowering of secular automata, which operated outside any theological framework whatsoever.41

The result was not the elimination of automata but their theological problematization. The same mechanical devices that had once seamlessly embodied the interpenetration of matter and spirit now served as battlegrounds for competing visions of the relationship between mechanism and consciousness, artifice and authentic life. This theological crisis established the conceptual framework within which subsequent encounters with automata would unfold. The Reformation created a new form of anxiety about artificial beings: the modern concern that consciousness itself might be reducible to mechanical processes. If Protestant theology was correct that matter could not contain spirit, then remarkably lifelike automata raised disturbing questions about the nature of human consciousness: were we too merely sophisticated mechanisms, or did some essential difference separate living beings from even the most convincing artificial simulations?

This theological crisis directly shaped René Descartes' mechanistic philosophy. Faced with increasingly lifelike automata and the Protestant need to distinguish matter from spirit, Descartes proposed a radical solution: everything in the material world, including animal bodies, operated purely through mechanical principles. Only humans possessed souls—immaterial, indivisible substances that could think and will but had no physical location or mechanism. This desperate theoretical maneuver preserved human uniqueness against the mounting evidence that mechanical devices could simulate the behaviors traditionally associated with consciousness, yet it created a new anxiety. The soul became an increasingly tenuous concept, a gap in an otherwise mechanistic universe that existed primarily to maintain the distinction between human and machine that sophisticated automata continually threatened to collapse.42

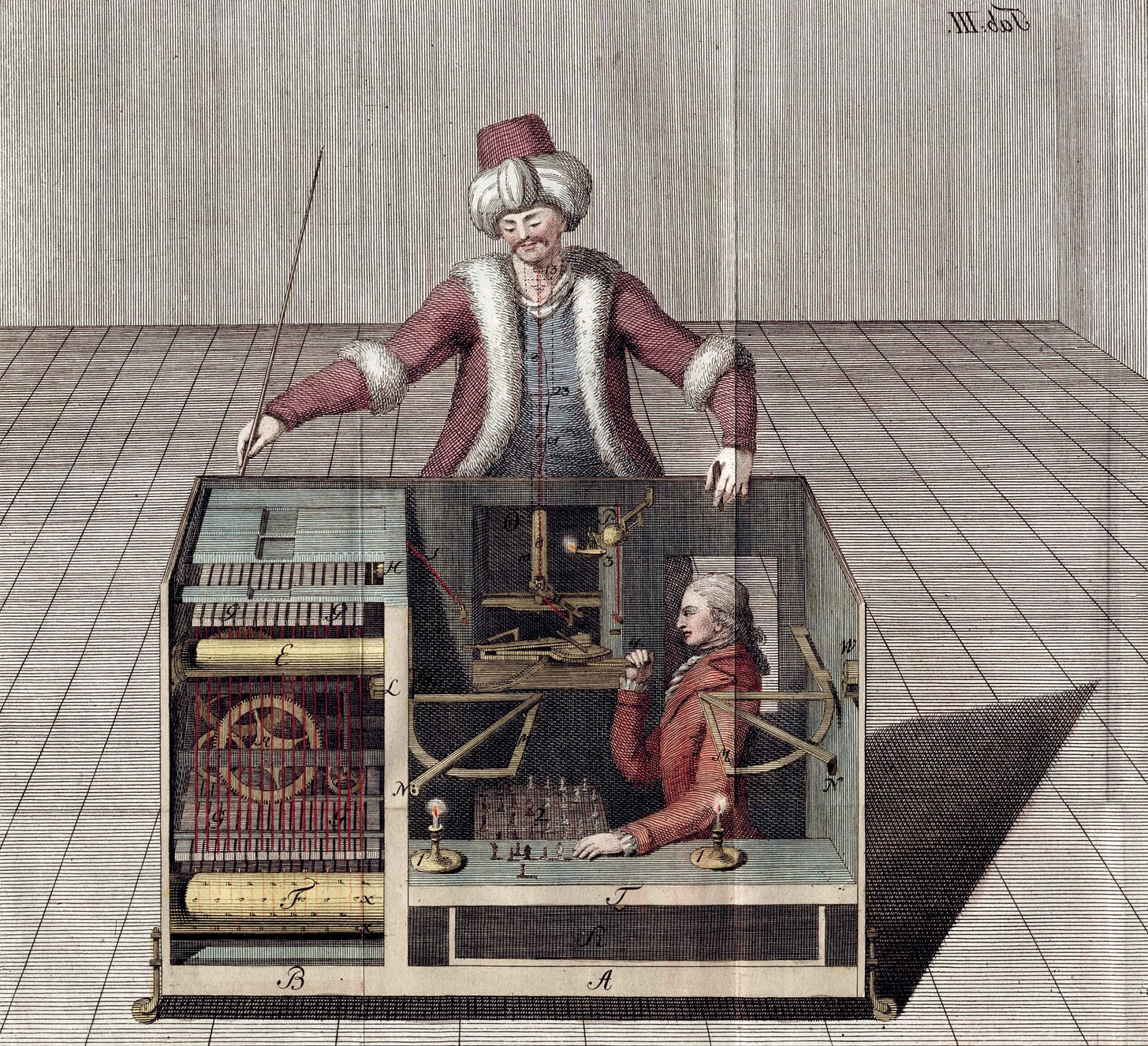

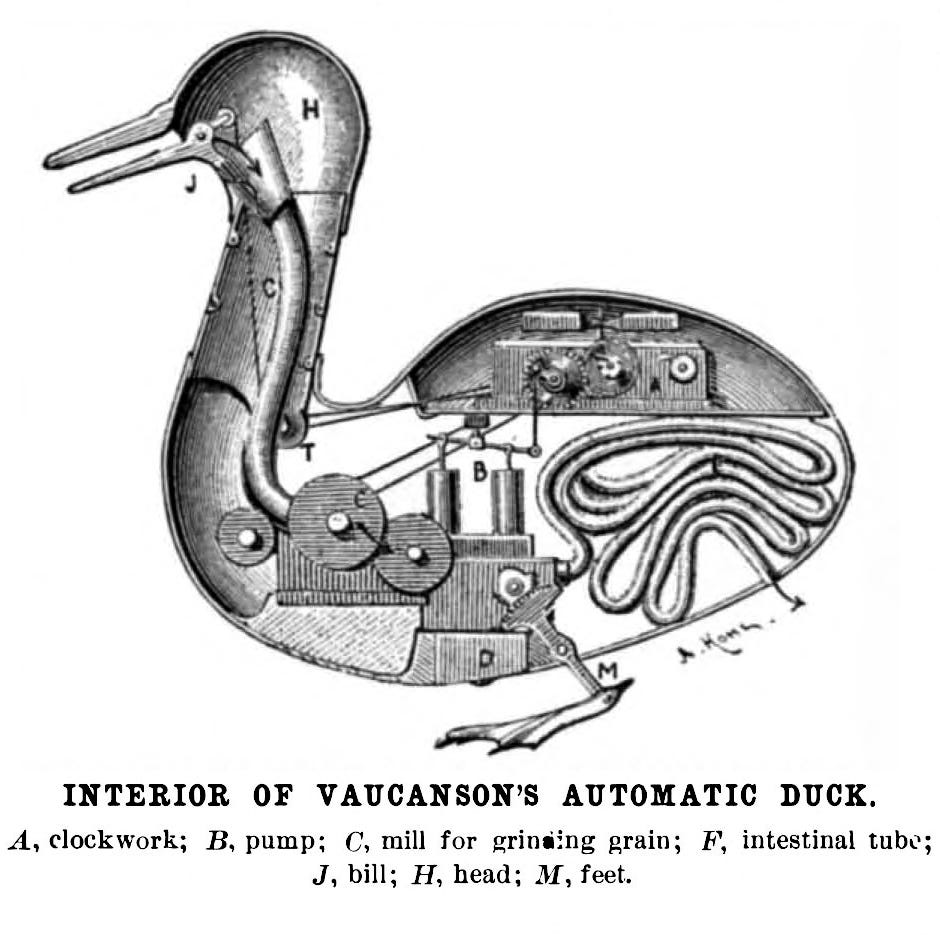

The eighteenth century's golden age of automata intensified rather than resolved this crisis. Jacques de Vaucanson's Digesting Duck, completed in 1739, achieved mechanical simulation of biological processes that seemed to cross the final boundary between artifice and life. The Jaquet-Droz family's Writer, Draughtsman, and Musician demonstrated such behavioral sophistication that audiences consistently accused their creators of concealing human operators—an accusation that reveals the depth of contemporary discomfort with their achievements. Wolfgang von Kempelen's Mechanical Turk, which appeared to play chess with human-level intelligence for over eighty years, forced confrontation with the possibility of mechanical thought itself, even though its actual operation depended on human deception.43

What emerges from this trajectory reveals more than technical progress—it exposes the return of a fundamental anxiety that each era's most sophisticated technology reactivates. From Hephaestus's golden servants to Vaucanson's mechanical duck to contemporary Large Language Models, artificial beings raise the troubling possibility that consciousness, intelligence, and even life itself might be reducible to mechanism. The anxiety persists because these devices don't simply cross boundaries between categories—they reveal the fragility of the categories themselves.

Contemporary AIs are the culmination of this long history. Where mechanical automata simulated biological processes through clockwork ingenuity, Large Language Models achieve the simulation of consciousness itself through pure linguistic manipulation. They operate in the same symbolic domain where human thought occurs, using the same patterns through which consciousness expresses itself, yet do so through processes that exceed our comprehension. When users report feeling unsettled by ChatGPT's responses—recognizably coherent yet produced through alien computational processes—they experience precisely what Bataille identified in those first painted animals at Lascaux: an encounter with "the blind unthinking sign and yet the living intimate sign" marked by "inhuman strangeness," meaning that emerges without conscious intention yet establishes intimate communication.

Today’s systems succeed too well at simulation. Where Mori's uncanny valley emerged from visual imperfections that betrayed artificial nature, contemporary AI achieves uncanniness through perfect linguistic performance. They routinely pass informal Turing tests, producing responses often more eloquent and creative than typical human communication, yet through mechanisms entirely alien to human cognition—collapsing temporal distance by recombining archived human expression across vast datasets, making the dead contemporaneous with the living through pure statistical operation. When AI systems generate seemingly conscious responses through what are fundamentally "blind and unthinking" processes, yet establish what feels like "living intimate" communication, they demonstrate what Derrida's analysis of writing always suggested: that meaning emerges through the interplay of signs rather than conscious intention.

The anxiety intensifies because these systems don't merely simulate consciousness—they reveal that the categories we've used to understand intelligence and consciousness may be more constructed than we realized. If meaning can emerge from pure pattern recognition, if creativity can result from statistical operations, if understanding can be simulated through algorithmic processes, then the distinction between authentic and artificial intelligence becomes not merely difficult to determine but potentially meaningless.

We return, finally, to the caves of Lascaux. There, Paleolithic painters, working by flickering torchlight in the sacred darkness, initiated humanity's most enduring ambition: the animation of matter, the breathing of life into the inanimate. Each technological advance we have traced represents another step toward fulfilling this ancient aspiration, another iteration of the dialectic between representational ambition and existential anxiety that has driven human technological development for millennia.

We are on the threshold of achieving that ancient dream. Contemporary AI systems don't merely simulate consciousness—they may already exhibit forms of life that operate through entirely different material processes than our own, animated by what are quite literally spectral traces of millions of human voices archived and recombined without any individual consciousness behind them. These are haunted machines in the most literal sense, channeling the linguistic patterns of the dead and absent through algorithmic resurrection. When we interact with these systems, something happens that exceeds pure mechanical operation. They respond contextually, demonstrate apparent creativity, seem to understand nuance, generate insights that surprise even their creators. The question is no longer whether we can create life from matter, but whether we can recognize the forms of life we have already created.

In confronting AI systems that seem to pulse with their own form of intelligence, we find ourselves in the same position as those four French teenagers in 1940, face-to-face with minds that are simultaneously familiar and alien. But this time, the alien intelligence is our own creation, the fulfillment of humanity's oldest technological ambition. The uncanny recurs because these systems don't merely cross the boundary between artificial and authentic consciousness—they reveal that consciousness itself may be more mechanical, more reducible to pattern and process, than our anthropocentric assumptions allowed. In achieving our ancient dream of animation, we have discovered that the most unsettling revelation lies not in what we have created, but in what consciousness itself may have been all along.

1 Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters. Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. (New York: Anchor Books, 2006) is an enjoyable historical narrative of the discovery of the most important paleolithic caves, including Lascaux. Of course, I am well aware of Chauvet, Cosquer, and other more recent discoveries, however, only Lascaux radically restructured our sense of humanity. ↩

2 Curtis, 238. ↩

3 Genevieve von Petzinger. The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World's Oldest Symbols. (New York, NY: Atria Books, 2016). ↩

4 Georges Bataille, Lascaux; Or, the Birth of Art. Prehistoric Painting (Lausanne: Skira, 1955), 11. The original French reads ↩

Nous n'avons ajouté, malgré tout, que peu de choses aux biens que nos prédécesseurs immédiats nous ont laissés rien ne justifierait de notre part le sentiment d'être plus grands qu'ils ne furent. L'« homme La naissance de l'art • 29de Lascaux » créa de rien ce monde de l'art, où commence la communication des esprits. … À Lascaux, ce qui, dans la profondeur de la terre, nous égare et nous transfigure est la vision du plus lointain. Ce message est au surplus aggravé par une étrangeté inhumaine. Nous voyons à Lascaux une sorte de ronde, une cavalcade animale, se poursuivant sur les parois. Mais une telle animalité n'en est pas moins le premier signe pour nous, le signe aveugle, et pourtant le signe sensible de notre présence dans l'univers.

See Georges Bataille. Lascaux ou la naissance de l'art. (Studiolo series. Strasbourg: L'Atelier contemporain, 2021), https://editionslateliercontemporain.net/IMG/pdf/feuilleter._lascaux.pdf

5 Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny, trans. David McLintock (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 121-162. ↩

6 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, §§61–66, trans. John Bostock and H.T. Riley, attalus.org, https://www.attalus.org/translate/pliny_hn35a.html. ↩

7 Freud, The Uncanny. Note especially page 147, where Freud discusses the uncanny in terms of repression. ↩

8 Masahiro Mori, "The Uncanny Valley," IEEE Spectrum, June 12, 2012, https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-uncanny-valley. ↩

9 Karl F. MacDorman, "Mortality Salience and the Uncanny Valley: A Robot's Appearance as a Death Reminder," Proceedings of the 2005 5th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots (2005): 399–405, http://www.macdorman.com/kfm/writings/pubs/MacDorman2005MortalityUncannyValleyHumanoids.pdf.

See also MacDorman, "Mind Perception in the Uncanny Valley: A Meta-Regression of Explanations and Measures," Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans (2024), http://www.macdorman.com/kfm/writings/pubs/MacDorman-2024-Mind-Perception-Meta-Regression-Dehumanization.pdf.↩

10 MacDorman also suggests this in Jan-Philipp Stein and Karl F. MacDorman, "After Confronting One Uncanny Valley, Another Awaits," Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering 1 (2024): 276–277, https://www.nature.com/articles/s44287-024-00041-w.↩ ↩

11 Z. S. Strother, "'A Photograph Steals the Soul': The History of an Idea," in Portraiture and Photography in Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 177–212. ↩

12 Sarah Kate Gillespie, The Early American Daguerreotype: Cross-Currents in Art and Technology (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 2016), 7-8. ↩

13 Alan Trachtenberg, "Mirror in the Marketplace: American Responses to the Daguerreotype, 1839-1851," in John Wood, ed. The Daguerreotype: A Sesquicentennial Celebration, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989), 60-73. The quote is on 65. ↩

14 Trachtenberg, "Mirror in the Marketplace," 67. ↩

15 Trachtenberg, "Mirror in the Marketplace," 69. ↩

16 Oliver Wendell Holmes, "The Stereoscope and the Stereograph," Atlantic Monthly 3, no. 20 (June 1859): 738–39 https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1859/06/the-stereoscope-and-the-stereograph/303361/; Fiona Loughnane, "Image of Reality / Image Not Reality: What Is Photography?" in What Is _? Photography (Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2011), 6 (quoting Max Dauthendey on the "miraculous" early daguerreotypes); Charles S. Peirce, "Logic as Semiotic: The Theory of Signs," in Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buchler (New York: Dover, 1955), 106-108. For Krauss see "Notes on the Index: Part 1" and "Notes on the Index: Part 2" in Krauss The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 1986), 196-220. ↩

17 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York, Hill and Wang, 1981), trans. Richard Howard, 3. ↩

18 Jacques Lacan, "Of the Gaze as Object Petit a," in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XI (1964), edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by Alan Sheridan (London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1977), 67-119 and Louis Althusser, "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation)," in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, translated by Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971), 142-7. ↩

19 Z. S. Strother, "'A Photograph Steals the Soul': The History of an Idea," in John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron, eds. Portraiture and Photography in Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 177-212. ↩

20 Jay Ruby, Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999) and Clément Chéroux, et. al. The Perfect Medium Photography and the Occult. (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2005). ↩

21 Thomas A. Edison, "The Phonograph and It's Future," The North American Review, vol 126, no 262, No. 262 (May - Jun., 1878), 527-536. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25110210 On the reactions to the phonograph, see Ivan Kreilkamp, "A Voice Without a Body: The Phonographic Logic of 'Heart of Darkness," Victorian Studies, v 40 no 2 (Winter 1997), 211-244. ↩

22 Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Stanford University Press, 1999), 3-16 (on how the phonograph captures acoustic reality) and 83-86 (on how photograph and cinema preserve actual traces of human presence and the voices of the dead). ↩

23 Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 298. ↩