After the Infrastructural City: On Abundance

A review of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson's Abundance

All times are weird, but some are more weird than others. In the space of a week, an unprecedented global economic apocalypse has become an imminent threat. I have multiple essays in the works, but the continued unravelling of the markets is deeply draining. I see nowhere to hide until there is relief from this insanity. That said, if you want to find some comfort in a possible vision of a better world, then read on for my take on Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance.

As always, this essay can be found on my site—https://varnelis.net/works_and_projects/after-the-infrastructural-city-on-abundance/—and if you click on the footnotes in this piece, they will take you there (no I won’t rewrite the code). To distract myself this rainy weekend, I remade the front page of varnelis.net to make navigation easier. Do visit. If you like this essay, restack and share.

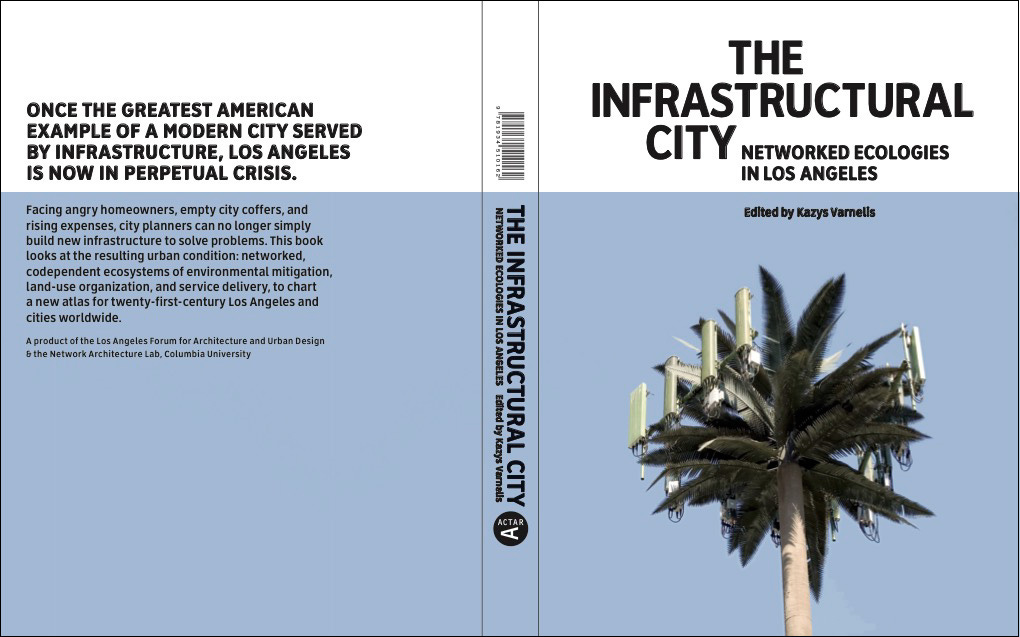

In 2008, my book The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles came out. To be clear, this wasn’t just my book. It was my vision and I edited it, but I assembled a team of architects at the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design to try to understand the metropolis through the lens of its underlying infrastructural systems. Taking Los Angeles as a paradigmatic modern city, the aim was to reveal how infrastructure, once the defining driver of urban growth and modernity, had begun to produce systemic crises and profound political impasses.

As I argued in the book’s introduction, infrastructure formed the core of Los Angeles’s identity—indeed, infrastructure was the city’s secular theology, its underlying belief system. Los Angeles arose not by accident or gradual organic growth but through deliberate, even heroic, acts of infrastructure: capturing distant rivers, electrifying deserts, and threading sprawling freeway systems across inhospitable terrain. Its birth represented human ingenuity overcoming ecological constraints. The modernist vision of infrastructure was a technocratic dream of reshaping unruly nature into orderly, productive landscapes. Infrastructure provided secular salvation for the American West, turning deserts into farmland, canyons into reservoirs, and remote valleys into thriving suburbs. Los Angeles embodied this vision more vividly than any other American metropolis. From William Mulholland’s aqueducts and the ambitious freeway system to distant electrical grids, the city’s infrastructures were built at vast scales, each project reinforcing the belief that ecological and geographic limits could always be transcended. Yet by the dawn of the twenty-first century, this triumph had given way to crisis, an infrastructural impasse born directly from the city’s prior successes.1

Reyner Banham famously celebrated this infrastructural landscape in his 1971 book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, describing the city through four interlocking ecological systems: Surfurbia (beach towns), Foothills (privileged hillside communities), Plains of Id (the sprawling, banal yet exuberant flatlands), and Autopia (the freeway network that tied it all together). Banham embraced Los Angeles as a decentralized, spontaneous city shaped by infrastructure rather than traditional urban planning. In doing so, Banham valorized what he called “Non-Plan,” a condition where bottom-up forces, consumer preferences, and private initiatives generated urban form free from bureaucratic constraints and grand masterplans.2

But by 2000—arguably even by 1980—the consequences of Banham’s Non-Plan were painfully evident. Instead of creating a liberating urban landscape, Non-Plan had set the stage for infrastructural dysfunction, political paralysis, and environmental degradation. Infrastructure now produced chronic dysfunction: aqueducts drained distant ecosystems and provoked political conflict, freeways were congested, air pollution was persistent, and entrenched NIMBYist politics stymied new infrastructural projects. Proposition 13, enacted in 1978, severely limited public funding, locking infrastructure into a state of permanent decay and inadequacy. Heroic infrastructure—massive, centralized, technocratic—had effectively come to an end. What emerged instead was a lasting infrastructural stalemate: political paralysis, ecological deterioration, and structural underinvestment.

Yet Los Angeles’s experience was not unique. As Edward Soja famously pointed out, Los Angeles is both an exception and the rule: a singular example that reveals broader trends.3 The infrastructural impasse evident in Los Angeles reflected conditions across America—neoliberal governance, entrenched individualism, private interests dominating public goods, and widespread resistance to new development. Our argument in the book was that infrastructure’s future would not be defined by grand heroic visions, but rather through difficult, continuous negotiations with ecological constraints, competing political demands, and limited resources. Seventeen years later, these fundamental issues persist: how can infrastructure meaningfully adapt, and can a compelling new vision emerge from what appears to be a landscape of perpetual impasse?

Shortly after The Infrastructural City appeared, Christopher Hawthorne, then architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, reviewed it prominently on the front page of the Culture section. This should have been a pivotal moment for us, bringing attention to a project that had taken years to produce. Instead, we were left disappointed. Hawthorne slammed our book as overly pessimistic, arguing that our emphasis on invisible systems, regulatory complexities, and entrenched political barriers dismissed too quickly the potential for visible, iconic infrastructure projects that could be created by starchitects like Norman Foster and Rem Koolhaas.4 In fairness to Hawthorne, he was writing in the hopeful early months of Barack Obama’s presidency, when substantial investment in infrastructure seemed imminent through the stimulus package being developed in response to the financial crisis. His optimism reflected precisely that brief historical moment. Once the Obama administration’s ambitious plans were tempered by political compromises, regulatory inertia, and the economic approach of funding the banks first favored by Director of the National Economic Council, Lawrence Summers, his assessment might have been gloomier.

More than that, Hawthorne’s optimism about architectural solutions to infrastructural problems reflects a persistent pattern in American discourse: the belief that our systemic challenges require merely aesthetic or technical fixes rather than fundamental political-economic restructuring. This misdiagnosis has continued to shape infrastructure debates in the years since our book’s publication. I will admit that we didn’t give a particularly optimistic polemic, but most recently, in their book Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson start out from a position remarkably similar to our own, arguing that show that America’s infrastructure problems remain stubbornly rooted in the invisible political-economic structures, regulatory barriers, and social conditions that we sought to reveal. Seventeen years after The Infrastructural City, the conditions we described have intensified rather than eased. Los Angeles remains trapped in infrastructural paralysis, reflecting a broader failure extending across California and, indeed, the United States as a whole. Little meaningful progress has been made in addressing fundamental urban crises—traffic congestion, housing affordability, ecological degradation—while political stalemates have deepened rather than resolved.

In Los Angeles specifically, infrastructure initiatives remain sporadic and insufficient. Ambitious projects promised decades ago, such as high-speed rail and comprehensive transit expansions, remain unrealized or delayed indefinitely. Traffic congestion has worsened, air quality improvements have stagnated, and despite efforts to promote transit-oriented development, the city still struggles with its legacy of automobile dependency. Water scarcity, predicted to become critical nearly two decades ago, is now acute, with the region stuck in cyclical drought emergencies while permanent solutions languish in political gridlock. Meanwhile, Proposition 13’s legacy continues to limit revenue streams, ensuring persistent underinvestment in public infrastructure. But these problems extend far beyond Los Angeles. Throughout California, similar infrastructural crises have emerged, emblematic of broader national trends. Housing shortages have driven soaring costs, contributing to an affordability crisis that increasingly drives young families out of the state. Homelessness, once confined to downtown skid rows, has become notoriously pervasive in California, most notably in Los Angeles and San Francisco, but throughout the state in general as well. Public education and transit remain underfunded, overcrowded, and inadequate, while the state’s famed climate initiatives repeatedly collide with stubborn local opposition and regulatory obstacles. In Abundance, Klein and Thompson explicitly identify California as the paradigmatic example of this broader American infrastructural and political impasse. As they put it bluntly:

“California’s problems are often distinct in their severity but not in their structure. The same dynamics are present in other blue states and cities. In this era of rising right-wing populism, there is pressure among liberals to focus only on the sins of the MAGA right. But this misses the contribution that liberal governance made to the rise of Trumpism. […] Donald Trump won by shifting almost every part of America to the right. But the signal Democrats should fear most is that the shift was largest in blue states and blue cities—the places where voters were most exposed to the day-to-day realities of liberal governance.”5

Klein and Thompson’s argument underscores that the dysfunction found in California—highly regulated yet infrastructurally stagnant, rhetorically progressive yet practically conservative—is symptomatic of deeper national failures. States across the country share California’s fate, caught in regulatory entanglements, financial constraints, and political paralysis that make meaningful infrastructure impossible to build. Federal attempts at infrastructural renewal, such as the Biden administration’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, have struggled to break through entrenched local resistance and bureaucratic inertia. Even when funded, projects stall at the state and municipal levels, tangled in endless public hearings, lawsuits, and regulatory hurdles. America finds itself stuck in the impasse first described nearly two decades earlier in Los Angeles. Infrastructure, which once symbolized national strength and optimism, now stands as a monument to collective failure. The broader infrastructural gridlock, first identified at a local level, has become a national condition.

Against this condition, Klein and Thompson offer perhaps a compelling retort: scarcity, particularly infrastructural scarcity, is not inevitable but chosen. America’s inability to build housing, transit, clean energy projects, and critical infrastructure is fundamentally a political problem, rooted in policy failures, regulatory barriers, and entrenched political and ideological opposition rather than technical or economic limitations. This argument reframes infrastructural impasse not as destiny but as an active political choice—a choice that can be reversed.

Klein and Thompson argue that both sides of the American political spectrum bear responsibility for the present stagnation. Conservatives, committed to shrinking government and relying exclusively on market solutions, have systematically undermined the public sector’s capacity to execute ambitious projects. Progressives, meanwhile, despite their rhetorical commitments, have often obstructed meaningful development through excessive regulation, overly cautious environmental policies, and local NIMBY resistance. The outcome has been pervasive paralysis and disillusionment—particularly visible in progressive strongholds like California.

Yet Klein and Thompson are not pessimists. They present a positive, forward-looking vision of what could be accomplished if political will aligned with technological capability. A new infrastructural abundance—marked by rapid housing construction, widespread deployment of renewable energy, modernized transportation networks, and equitable urban growth—is entirely achievable, they assert, provided regulatory and ideological barriers are dismantled and public ambitions are renewed. Their solution is clear: the United States must build more, faster, and smarter, to address chronic shortages in housing, energy, healthcare infrastructure, and transportation. Abundance, in their view, represents not merely an economic or technological goal but a necessary political project—a pathway out of the stasis and frustrations of contemporary American life. Their central solutions involve streamlining regulatory processes, significantly accelerating permitting timelines, boosting public investments in infrastructure projects, and revitalizing government agencies’ capacities to execute ambitious, large-scale developments.

Abundance has emerged at a moment when it offers the only coherent alternative vision for Democrats to counter the oligarchic power grab of the Trump administration. It is compelling and doesn’t retread the tired identity politics that has led Democrats to defeat after defeat. Yet Abundance has not gone unchallenged and this critique can lead to a further, better development. For sure, I haven’t had the opportunity to review every critique, but I’d like to mention two. In “Move Fast and Break Things,” Jay Pinho argues that Abundance offers an “intoxicating vision” whose “central complaint rings agonizingly true” regarding governmental dysfunction, but ultimately fails to address the fundamental political questions at its core. Who decides what gets built? Whose abundance matters most? What democratic processes must be preserved even as we streamline decision-making? Pinho persuasively highlights the case of conservative venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who publicly advocated for building more while privately opposing multifamily housing near his own property—illustrating the gap between abstract abundance advocacy and concrete political choices. “Here lies The Messy Real World,” he writes, suggesting that the same problems we identified in the Infrastructural City haven’t really gone away. But Pinho adds that the “the at-times painstaking slowness of government is itself the product of democratic responsiveness, of accountability.” Losing that accountability would be dangerous. Similarly, in “An Abundance of Credulity,” Hannah Story Brown criticizes Klein and Thompson for advocating governmental efficiency at the expense of democratic safeguards, arguing that they evade a crucial question: who benefits from scarcity? As Brown observes, infrastructural stalemates aren’t merely bureaucratic accidents but often serve powerful interests—fossil fuel companies profit from climate inaction and housing conglomerates thrive on constrained supply. This analysis resonates with our findings in The Infrastructural City, where we documented how infrastructure impasses reflect not just procedural failures but entrenched power dynamics. And like Pinho, she argues that the “Rules imposed over the last half-century that seek to prevent exploitation and safeguard the public have led to dramatically lower air and water pollution, significantly fewer auto and aviation fatalities, reduced mortality from infectious diseases, fewer deaths and injuries at work, fewer deaths from residential fires, fewer bank failures, and a less volatile economy. Some of us believe those are worthwhile trade-off.”6

These critiques illuminate what might be called Abundance’s democratic dilemma: how to enable decisive infrastructure development while preserving accountability and ensuring equitable outcomes. This is not merely a technocratic challenge but a fundamentally political one. Klein and Thompson correctly identify that America’s inability to build stems from policy choices rather than inevitable constraints, but their reluctance to confront the politics of those choices—who wins, who loses, and whose voice matters in the process—is a stark limitation of their approach.

Yet these critiques need not lead to pessimism about infrastructure’s future. Instead, we can take away from them the idea that addressing our infrastructural impasse requires not just procedural reforms but democratic renewal, something that is going to have to happen to rebuild the United States after, it increasingly seems, the Trump administration runs it into the ground. While streamlining permitting and boosting public investment are necessary components of an abundance agenda, they must be paired with strengthened accountability mechanisms and explicit attention to equity, less in terms of an endless cycle of identity politics grabs and more in terms of ensuring that the profits generated by this new policy do not flow ever upwards to the same billionaire oligarchy that has so supported Trump. More than that, it would be appropriate that a new Democratic platform should expressly task itself with a significant tax increase on the billionaire class—here we can follow Trump’s hallowed MAGA dictum of a return to the 1950s and impose a 91% marginal rate on individuals earning more than $2 million a year— while also establishing a graduated corporate income tax to create a more competitive market.7

More than that, any viable vision for infrastructural abundance must also confront a reality that both Klein and Thompson and their critics largely overlook: the coming demographic contraction that will fundamentally reshape our infrastructural needs and possibilities. While Klein and Thompson explicitly distance themselves from advocates of voluntary degrowth—those who propose deliberately shrinking economies and populations for ecological reasons or to preserve the character of their communities—they fail to address what we might call “actually-existing degrowth”: the unplanned, ongoing demographic decline already occurring across much of the developed world. Populations are already shrinking significantly in countries like Japan, South Korea, and most European nations, driven by persistently low fertility rates, aging populations, and changing social patterns. This phenomenon, increasingly evident even in the United States—where the total fertility rate is 1.62—signals a profound structural shift that will fundamentally reshape urban and infrastructural planning in coming decades, regardless of our political preferences. While immigration may keep America’s population growing for a time, that has its limits and is likely to slow considerably before Democrats take power due to the MAGA agenda.

As I have done before, I will again borrow novelist William Gibson’s evocative term “the Jackpot” to refer to this unfolding demographic transition. Rather than a sudden apocalyptic population collapse, the Jackpot describes a slower, distributed unraveling—a prolonged and uneven demographic downturn, intensified by climate stress, economic instability, and shifting cultural values. In the United States, signs of the Jackpot’s approach are increasingly clear: declining birthrates, shrinking rural and small-town populations, aging demographics, and regional depopulation. The hard truth is that most of these areas are not fixable. If infrastructure planning and political visions adopt the Abundance Agenda but fail to acknowledge this demographic reality, the country risks investing in futures that will never materialize, preparing for continued growth while confronting the steady reality of shrinkage.

Crucially, demographic contraction coincides with—and is amplified by—the rise of Artificial Intelligence. Rather than viewing AI merely as a threat stealing jobs, it will be embraced as a tool to ease the social and economic adjustments required by shrinking populations. AI’s widespread deployment is already reshaping labor markets, significantly reducing demand for traditional labor across industries. This shift could alleviate some economic pressures posed by a shrinking workforce, helping facilitate a smoother transition toward sustainable, high-quality urban life. Yet precisely how we harness AI while mitigating the profound disruptions likely from automation—especially the potential mass displacement in service and intellectual sectors previously insulated from the upheavals experienced by industrial labor during post-Fordism—is perhaps the most critical question we face regarding AI today. No matter how challenging this is for many progressives—who often view AI as deeply flawed or irredeemably captured by corporate interests—AI-optimized infrastructures, such as smart energy grids, autonomous transit systems, predictive healthcare networks, and intelligent urban management platforms, can help societies navigate demographic contraction efficiently and equitably. In this scenario, infrastructural abundance becomes redefined: not merely building more, but building better—investing in adaptive, intelligent infrastructures that enhance human and ecological well-being as populations decline.

However, integrating the Jackpot scenario into the abundance argument demands redefining abundance itself. Rather than pursuing endless quantitative expansion, infrastructure must become adaptive, resilient, and oriented toward ecological regeneration and urban livability. A future of smaller populations offers genuine opportunities: cities redesigned around quality of life rather than growth alone, restored ecosystems, and revitalized urban spaces characterized by abundant green infrastructure, sustainable energy systems, and human-scale design.

Yet achieving this vision faces political headwinds. The political Right portrays degrowth and adaptive urban strategies as part of a conspiratorial ‘Great Reset,’ framing necessary adaptations as threats to personal freedom, economic prosperity, and American cultural identity. This ideological stance complicates practical discussions about managed shrinkage by conflating sustainability with politically charged fears of elite control, making constructive bipartisan solutions harder to achieve. Yet a realistic reckoning must still occur in declining areas. Citizens need to be actively brought into the planning process, clearly addressing their understandable anxieties and explicitly answering the fundamental question: ‘What can we do to make things better for our communities as the population continues to fall?’ Nor is this a matter only for Blue states. The state with the largest population decline is West Virginia and no amount of Trump subsidies for coal will ever bring the miners back.

Fortunately, this strategy doesn’t require reinventing the wheel. Europe and Japan have developed methods for managing urban shrinkage. In the United States, Youngstown, Ohio developed a plan to explicitly acknowledge population decline, consolidating services and converting vacant lots into urban agriculture. Even though implementation remained limited due to persistent economic challenges, constrained municipal resources, and political resistance to fully abandoning growth-oriented strategies, the plan still represents an instructive American precedent in accepting shrinkage explicitly. Japan’s “compact city” policies, exemplified in Toyama, have strategically concentrated development around transit nodes, allowing peripheral zones to revert gradually to nature and creating more vibrant, walkable urban cores despite overall population decline. Detroit’s strategic framework similarly strives to establish higher-density neighborhoods surrounded by green infrastructure and innovative urban agriculture. These examples demonstrate how thoughtfully managed shrinkage can lead to more sustainable, livable urban environments. I have spent time in West Virginia. It is a beautiful state and I can see why people who live there don’t want to leave. But there is little reason that we can’t rethink it and make a large part of the state into an incredible national park that would be a worldwide draw. Even the coal mines can be recovered, turned into models for ecological reclamation.

Infrastructure after growth represents not a reduction of ambition but a recalibration of priorities toward genuinely sustainable abundance. America can break this deadlock by embracing the Abundance agenda—curtailing excessive governmental constraints and strategically collaborating with industry to advance technological innovation. Rejecting identity politics that frame society as composed of factions competing over an ever-dwindling pie, this vision instead offers tangible improvements in everyday life: lower costs of living, better public services, cleaner air and water, strengthened local economies, and greater accessibility. Yet confronting the emotionally appealing but misleading nostalgia of MAGA requires political leaders to reframe demographic contraction and technological transformation as opportunities rather than threats, enhancing our quality of life and the ecological sustainability of the country. The path forward lies in reconciling three critical dimensions: the technical challenge of building more efficiently, the political challenge of ensuring equitable distribution and meaningful democratic participation, and the demographic challenge of adapting to population contraction. Ultimately, resolving the infrastructural impasse identified nearly two decades ago demands not only wise policies but compelling voices—like Klein and Thomposon’s—capable of articulating a credible, hopeful vision of ecological restoration, social renewal, and enduring resilience.

This integrated approach suggests a vision of abundance quite different from the endless expansion of the modernist era and that is, unfortunately, something lacking from Abundance at present, but it can be part of the Abundance agenda. Rather than merely building more of the same infrastructures that characterized 20th-century development, we must build better—creating adaptive, resilient systems that enhance human well-being and ecological health as populations potentially decline. This vision of abundance embraces quality over quantity, recognizing that democratic accountability and ecological sustainability are not impediments to progress but essential components of truly meaningful advancement.

1. Kazys Varnelis, “Introduction. Networked Ecologies,” The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles (Barcelona: Actar, 2008), 6-16. ↩

2. Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (London: Allen Lane, 1971) ↩

3. Edward W. Soja, Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (New York: Verso, 1989), 191. ↩

4. See Christopher Hawthorne, “What’s the Future of ‘The Infrastructural City of L. A.,” The Los Angeles Times, February 15, 2009, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-ca-infrastructural-city15-2009feb15-story.html. Harvey Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 82, no. 2, (September 1976), 309-332. https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~hoganr/SOC 602/Spring 2014/Molotch 1976.pdf ↩

5. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2009), 17. ↩

6. Jay Pinho, “Move Fast and Break Things,” Networked Substack, April 1, 2005

and Hannah Story Brown, “An Abundance of Credulity,” The American Prospect, March 26, 2025, https://prospect.org/culture/books/2025-03-26-abundance-of-credulity-klein-thompson-dunkelman-review/ ↩

7. Kimberly Clausing, “Combating Market Power Through a Graduated U.S. Corporate Income Tax,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, April 15, 2024, https://equitablegrowth.org/combating-market-power-through-a-graduated-u-s-corporate-income-tax/ ↩